“Climate breakdown has begun,” declared UN Secretary-General António Guterres. Guterres is not a climate expert himself, but in this case, he’s basing his opinion on the data and analyses generated by the actual experts. If you thought this year was a bit of a weather suffer-fest, it probably wasn’t your imagination, as the Northern Hemisphere has just experienced its hottest summer on record, driving the year to date into the second-hottest position.

While the weather isn’t climate, the climate sets limits on the sort of weather we should expect. And a growing number of analyses of this year’s weather show that climate change has been in the driver’s seat for several events.

Hot, hot, hot

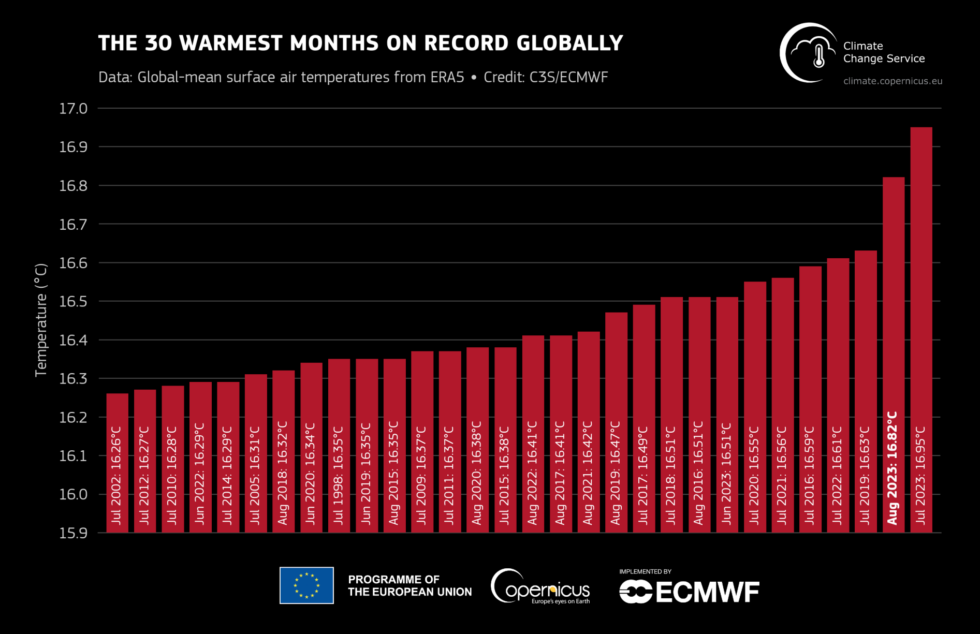

On Wednesday, the World Meteorological Organization released its August data, showing that the month was the second hottest on record and the hottest August we have experienced since temperature records have been maintained. The only month that has ever been warmer is… the one immediately before it, July 2023.

July and August are part of the three-month summer period for the Northern Hemisphere, and the heat of the past two months has made this the hottest summer on record as well, with the temperature anomaly being a full 0.2° C above any previous month. (For context, climate change to date has only pushed recent temperature anomalies to about 0.8° C above last century’s average temperatures.) The blazing hot summer has also pushed 2023’s year-to-date temperature into second place on the overall list, behind only 2016.

2016 was notable for having the strongest El Niño so far this century. By contrast, 2023 is just now tipping over into a weak El Niño. Although sea surface temperatures are also setting records this year, we have yet to feel the full impact of the warming of this phase of the Southern Oscillation. Should the El Niño strengthen, this is likely to end up the warmest year on record.

For those in the US, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has yet to release data on August but found that July was the 11th-warmest month on record in the contiguous 48 states. While four states—Arizona, Florida, Maine, and New Mexico—experienced their hottest months on record, several states in the northern Great Plains experienced lower temperatures than usual, moderating the overall temperature.

Yes, it’s been climate change

While this is the sort of weather you’d expect to experience as the climate heats up, it’s more challenging to attribute these events directly to climate change. But the World Weather Attribution team has worked out a methodology for doing just that: estimating how our warming climate has influenced the probability of specific weather events. So far, it has worked out how climate change may have influenced three heat waves that happened earlier this year, along with the weather that fostered wildfires in Canada.

A signature of human-driven climate change is obvious in much of them. An April heat wave in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula was determined to be “almost impossible without climate change.” Heat and humidity that struck Southeast Asia at roughly the same time was termed “largely driven by climate change.”

More relevant to this summer, the team looked at heat waves that struck China, Europe, and North America in July. It found that, given the warming that has occurred due to climate change, these events are not uncommon. Heat waves of this magnitude should be expected every five years in China, 10 years in Europe, and 15 years along the US-Mexico border. But, without the warming we’ve experienced, China’s heat wave would be a one-in-250-year event, and the US and European heat waves would be “virtually impossible.”

In much of North America, the experience of the early summer was frequently disrupted by smoke from wildfires spread widely across Canada. The attribution project looked at the warm and dry conditions that helped fuel the spread of these fires and found that climate change has made it twice as likely.

Combined, it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that, for much of the Northern Hemisphere, the summer would have looked very different if it weren’t for the climate change that our carbon emissions have driven.

The big picture

While 2023 remains a work in progress, NOAA has just released a detailed analysis of 2022, showing that the concentrations of some greenhouse gases—carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—all reached record concentrations last year. And, while 2022 didn’t set an overall record due to the cooling influence of La Niña conditions, it was the hottest La Niña year on record.

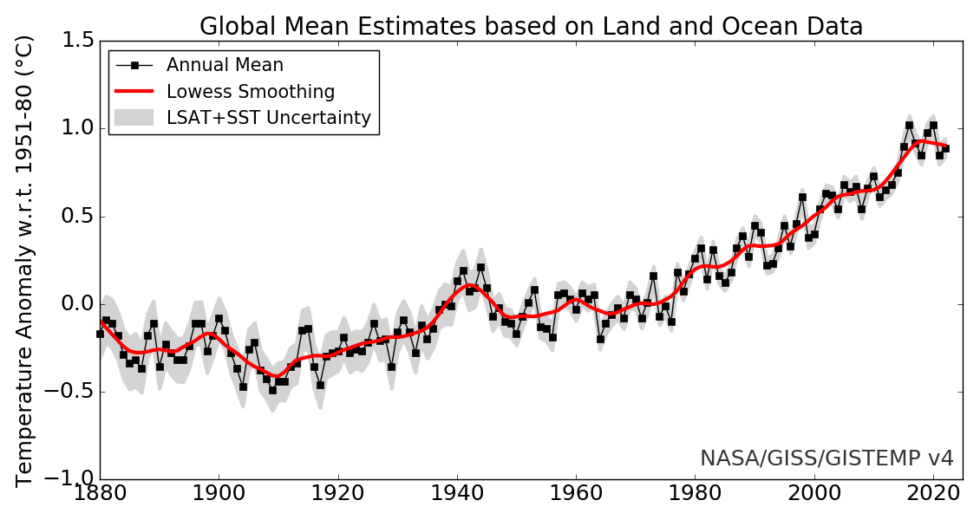

NOAA also concludes that the last eight years, from 2015 to 2022, were all within the hottest eight years ever recorded. Barring a one-off event like a major volcanic eruption, 2023 will make that nine in a row.

And, within the longer-term trends, none of this is anything new. By the end of this month, everybody alive who’s never experienced a month with temperatures below the 1951–1980 average will have experienced their 31st birthday.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1966336