SAN FRANCISCO—In highly-anticipated testimony wrapping up the second day of trial, former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick confirmed that Uber’s primary competitor in self-driving cars is indeed Waymo, now a division of Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

“Do you believe they are in the lead?” Waymo’s attorney, Charles Verhoeven, asked him.

“Yes,” Kalanick said.

“And they were in the lead in 2015 and 2016?”

“Correct.”

Kalanick, who served as Uber’s CEO from 2010 until mid-2017, also admitted that he met with Anthony Levandowski, a top Waymo engineer, in 2015.

“You discussed the purchase of a non-existent company?”

“Yes, he was very adamant about starting a company, and we were very adamant about hiring him,” Kalanick said, who was dressed in a dark suit and tie, remained reserved throughout his 45 minutes of testimony. His answers by and large were limited to single words: “yes,” or “correct.”

Waymo and Uber are locked in an intense trial over whether Uber misused trade secrets acquired from Waymo—the result of the case could determine who ends up on top in the autonomous vehicle space.

“Laser is the sauce”

Kalanick acknowledged that, in 2015, Uber was facing an existential crisis. The ridesharing company knew that it was behind in autonomous vehicles and would potentially be driven out of business.

“If you are not making new things that people want, then you become part of the past,” Kalanick said.

So, that’s what prompted Uber—particularly Kalanick—to seek out Levandowski, who was feeling frustrated at Google.

Verhoeven showed showed notes of Kalanick speaking at a meeting held in late 2015 with key members of Uber’s AV team. Those notes, which were taken by John Bares, who left Uber late last year, featured a wishlist that read: “source, all of their data, tagging, road map, pound of flesh, IP.”

“Did you tell the group that what you wanted was a pound of flesh?” Verhoeven asked.

“I don’t know specifically,” Kalanick said. “It’s a term I use from time to time.”

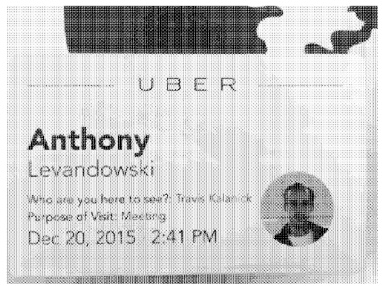

At one point in December 2015, Levandowski also met with Kalanick at Uber headquarters. A photocopy of Levandowski’s temporary ID badge was entered into evidence.

Kalanick further explained that, during a meeting on Sunday, January 3, 2016—an encounter described as a “jam sesh,” likening it to a jazz jam session—where Kalanick met with Levandowski and others directly. That’s when Kalanick wrote on a white board: “Laser is the sauce.” (A picture of this was shown in court.)

“I’d say it’s an important part of making autonomous work,” he explained in court. “It doesn’t work without it.”

In other words, lasers, or lidar, were and remain essential to the development of any self-driving car.

When Verhoeven asked if the two men had discussed the purchase of a “non-existent company,” Kalanick explained that the two men wanted to take different routes to achieve ultimately the same goal

“Yes, he was very adamant about starting a company and we were very adamant about hiring him,” the ex-CEO said.

Verhoeven then launched into a step-by-step timeline that Uber and Ottomotto agreed to, where Levandowski and his team would achieve certain multi-million dollar bonuses if they hit various self-driving milestones. However, the clock ran out and US District Court Judge William Alsup has been running a tight schedule, ending court each day at 1pm PT.

Kalanick only testified for 45 minutes and was told to report back to court Wednesday morning at 7:30am for the third day of trial.

What is a trade secret, anyway?

Kalanick was the main event—heads turned in anticipation of his arrival in court.

However, there were a few other moments of fireworks. Earlier in the day, Gary Brown, a Google security engineer, was hammered while on the witness stand under questioning by Uber’s top lawyer, Arturo González.

Brown was part of the team that analyzed the network traffic and examined Anthony Levandowski’s work-issued laptop that was used to download over 14,000 internal Waymo files from its SVN server shortly before his departure from Waymo in January 2016.

After Brown walked the jury through precisely how he determined how it was Levandowski that downloaded the files, during cross-examination, González asked if any “alarm bells” went off when such a huge cache of data was downloaded.

“Not to my knowledge,” he said.

“Who is the person at Google that is responsible?” the lawyer asked.

“I’m not sure,” Brown said, flatly.

“Nobody! Nobody at Google supervised that SVN!” he said, animatedly, looking and gesturing straight at the jury, underscoring the crux of Uber’s argument, that even if Levandowski took the files, they were not trade secrets.

“If these documents were important, don’t you think that would be a good idea to know if somebody downloaded everything?”

“It’s possible, but it’s very hard to detect malicious insiders.”

“It’s not hard when somebody downloads the entire database, is it?”

“I don’t know.”

On a redirect questioning from a Waymo attorney, Brown underscored that it wasn’t his job to protect the SVN server—all he was in charge of was evaluating the network and forensics logs after the fact. But the point was made: if the files that Levandowski accessed prior to his departure from Waymo were so secret, they certainly weren’t protected very well.

This is a crucial element of trade secrets law: are the techniques and methods in question truly secretive?

This is what this lawsuit boils down to: did Uber steal, or misappropriate, eight specific trade secrets? The public does not yet know precisely which details are at issue—the court is taken into a closed session when those precise elements are discussed in court.

Earlier in the day, before Brown took the stand, US District Court Judge William Alsup gave a quick primer to the jury about the differences between patents and trade secrets, reminding the jury that the case only revolved around the latter.

“No government agency issues a trade secret,” he said. “Instead it’s something that typically a company or a small business or big business that would come up with their own way of doing something. They kept it secret—it has economic value because it is secret—and they take reasonable efforts to keep it a secret. That’s what a trade secret is.”

Judge Alsup highlighted the fact that trade secrets could be created separately, independently.

“You can only sue over stealing or misappropriation of trade secrets,” he said.

Still, Levandowski is the elephant in the trial: the crucial engineer downloaded 14,000 files shortly before he left Waymo in January 2016. He is likely to be called to the witness stand. If he shows up, he’s not likely to give any substantive answers—when summoned for a deposition he declined, citing a Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

The lawsuit, Waymo v. Uber, began back in February 2017, when Waymo sued Uber and accused Uber of misusing trade secrets that Levandowski took from Waymo. The engineer went on to found a company that was quickly acquired by Uber. Levandowski refused to comply with his employer’s demands during the course of this case and was fired. Uber has denied that it benefited in any way from Levandowski’s actions.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1255565