Roughly 110 years ago, one of the world’s greatest aircraft designers—Clarence “Kelly” Johnson—was born in Ishpeming, Michigan. And since we’re gigantic aviation nerds here at Ars Technica, the week of his birthday (February 27) is as good a reason as any to celebrate some of his legendary designs. Johnson spent 44 years working at Lockheed, where he was responsible for world-changing aircraft including the high-flying U-2, the “missile with a man in it” F-104 Starfighter, and the almost-otherworldly Blackbird family of jets.

In his career at Lockheed, Johnson’s engineering acumen won him two Collier trophies, the most prestigious award one can win in the field of aeronautics (Lockheed chief engineer Hall Hibbard once famously said about Johnson, “That damn Swede can see air!”). In addition to being an excellent engineer, Johnson was also a powerfully effective manager; his practices running Lockheed’s Advanced Design Projects unit are commonly regarded now as a master-class on how small focused groups should communicate and manage projects.

But it is for his airplanes that Kelly Johnson is most remembered.

The early years

Johnson was born in 1910 to Swedish immigrants Peter and Christine Johnson. The seventh of nine children in a loving but very poor family, he was a bright and industrious child captivated at an early age by the idea of designing airplanes—something he credited to reading Tom Swift stories. In 1929 he enrolled at the University of Michigan to study aeronautical engineering. Ever the industrious fellow, he and a friend persuaded the faculty to let them use the university’s wind tunnel when it was idle. Clients who benefited from his early aerodynamic work included Studebaker, Pierce, and even some Indianapolis racers.

After graduating in 1932, he drove out west to California and secured a job at Lockheed, the company he would stay with throughout his entire career. He proved to be a precocious new hire, telling his new bosses that the plane they had just designed—the Lockheed Electra, which the company was depending upon—wasn’t up to scratch. They tasked him with fixing the problem, which he did at his old university wind tunnel in Michigan. The result was the Electra’s distinctive double vertical tail, a feature that soon showed up on more Lockheed aircraft.

P-38

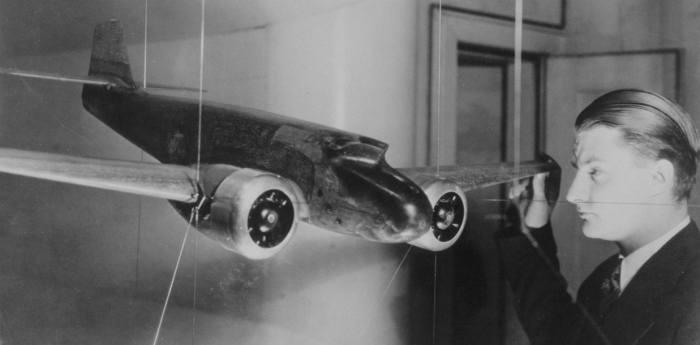

In the late 1930s with war looming in Europe, the US Army Air Corps was waking up to the need for better aircraft. Lockheed won a contract to develop a new fighter with an unrivaled top speed: 400mph (643km/h). That plane was to be the P-38. It was distinctive-looking plane, with a pair of engines, each in its own boom. The cockpit was in a pod in-between.

The P-38’s top speed exposed the plane to an little-understood aerodynamic effect, called compressibility. Essentially, as airspeed increased, shockwaves formed at the leading edge of control surfaces, causing them to lock up and sending the plane into a stall. Although Johnson and his team were unable to solve the problem on the P-38—one that cost several pilots their lives—they were able to ameliorate it with flaps mounted on the wings that would slow the plane enough for control to be regained.

The P-38 proved to be an effective jack-of-all-trades, serving in Europe and the Pacific in a number of roles, including long-range escort, ground attack, night operations, and reconnaissance. Over 10,000 were built throughout the war.

P-80

-

The Xp-80A prototype, being flown by Lockheed’s test pilot Tony LeVier.

-

Four F-80s flying in formation.

-

The T-33, a trainer variant of the P-80/F-80. Seen here at the Los Angeles County Air Show.

The P-38 was fast, but propeller-driven airplanes had their limits, and over in the UK Frank Whittle’s new jet engine was about to make them obsolete. In 1943, Johnson proposed the idea of Lockheed building a jet fighter and doing so in an extremely short amount of time—180 days—in order to get it into service to help the war effort. But with Lockheed’s Burbank plant already running around the clock to build other planes, he had a problem. There was no space, and few engineers available to help.

He sought and received permission to set up his own experimental department, which he based in a hangar next to Lockheed’s wind tunnel. With his team working 10-hour days, six days a week, the prototype was ready just 143 days later. That plane was the P-80 Shooting Star. It arrived too late to have an impact in WWII, but (renamed the F-80) it went on serve in Korea, and a training variant—called the T-33—was in service well into the 1980s.

Though officially named the ADP unit (first for “Advanced Development Projects” and then “Advanced Development Programs”), Johnson’s experimental aircraft unit became known informally within Lockheed as the “Skunk Works,” a reference to one of the characters in the comic strip L’il Abner, who would brew up a foul “skonk oil” in an unspecified and secret location. The name was formally adopted by Lockheed in the 1960s, and the term “skunk works” has since become shorthand for any kind of advanced research and development unit within a company.

F-104

-

Early F-104s in formation. It was an elegant plane.

-

A pair of F-104As.

-

F-104s at Taoyuan Air Base in Taiwan.

-

Although the F-104 had a limited service life with the USAF, many thousands were sold to other countries.

-

F-104s killed more than 100 West German pilots.

Next up was the F-104 Starfighter, a single-engined interceptor that could give pilots two things they wanted after their experience in Korea: speed and altitude.It would be capable of twice the speed of sound, and to do so, it was shaped like a rocket, with stubby, extremely thin, razor-sharp wings. The F-104 first flew in 1954 and was quickly dubbed “the missile with a man in it” due to its Mach 2-plus top rated speed. However, many of the features that made the F-104 so quick also made it a difficult to fly–most notably those stubby wings. That problem was compounded on early models with an ejector seat that fired down through the bottom of the cockpit. Ejection at low altitude cost many pilots their lives.

The F-104 is looked at as an icon, and it set a number of speed and altitude records, but looked at dispassionately it wasn’t a particularly efficient or effective airplane. The US Air Force bought fewer than 300, retiring them all by 1965. Several thousand were built for other countries—helped in part by bribery scandals. In West Germany it killed more than 100 pilots, earning nicknames like “the flying coffin” and “the widowmaker.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=838075