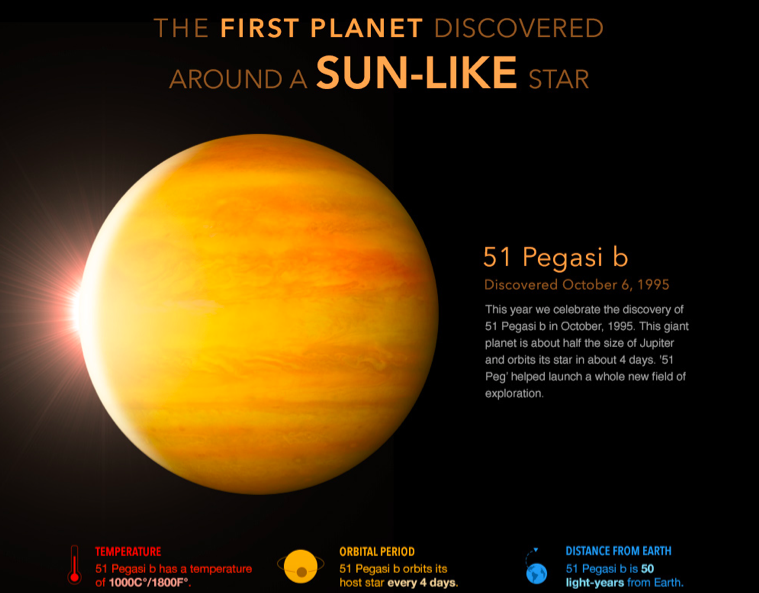

In 1995, after years of effort, astronomers made an announcement: They’d found the first planet circling a sun-like star outside our solar system. But that planet, 51 Pegasi b, was in a quite unexpected place—it appeared to be just around 4.8 million miles away from its home star and able to dash around the star in just over four Earth-days. Our innermost planet, Mercury, by comparison, is 28.6 million miles away from the sun at its closest approach and orbits it every 88 days.

What’s more, 51 Pegasi b was big—half the mass of Jupiter, which, like its fellow gas giant Saturn, orbits far out in our solar system. For their efforts in discovering the planet, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz were awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for Physics alongside James Peebles, a cosmologist. The Nobel committee cited their “contributions to our understanding of the evolution of the universe and Earth’s place in the cosmos.”

The phrase “hot Jupiter” came into parlance to describe planets like 51 Pegasi b as more and more were discovered in the 1990s. Now, more than two decades later, we know a total of 4,000-plus exoplanets, with many more to come, from a trove of planet-seeking telescopes in space and on the ground: the now-defunct Kepler; and current ones such as TESS, Gaia, WASP, KELT and more. Only a few more than 400 meet the rough definition of a hot Jupiter—a planet with a 10-day-or-less orbit and a mass 25 percent or greater than that of our own Jupiter. While these close-in, hefty worlds represent about 10 percent of the exoplanets thus far detected, it’s thought they account for just 1 percent of all planets.

Still, hot Jupiters stand to tell us a lot about how planetary systems form—and what kinds of conditions cause extreme outcomes. In a 2018 paper in the Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, astronomers Rebekah Dawson of the Pennsylvania State University and John Asher Johnson of Harvard University took a look at hot Jupiters and how they might have formed—and what that means for the rest of the planets in the galaxy. Knowable Magazine spoke with Dawson about the past, present and future of planet-hunting, and why these enigmatic hot Jupiters remain important. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What is a hot Jupiter?

A hot Jupiter is a planet that’s around the mass and size of Jupiter. But instead of being far away from the sun like our own Jupiter, it’s very close to its star. The exact definitions vary, but for the purpose of the Annual Review article we say it’s a Jupiter within about 0.1 astronomical units of its star. An astronomical unit is the distance between Earth and the sun, so it’s about 10 times closer to its star—or less—than Earth is to the sun.

What does being so close to their star do to these planets?

That’s an interesting and debated question. A lot of these hot Jupiters are much larger than our own Jupiter, which is often attributed to radiation from the star heating and expanding their gas layers.

It can have some effects on what we see in the atmosphere as well. These planets are tidally locked, so that the same side always faces the star, and depending on how much the heat gets redistributed, the dayside can be much hotter than the nightside.

Some hot Jupiters have evidence of hydrogen gas escaping from their atmospheres, and some particularly hot-hot Jupiters show a thermal inversion in their atmosphere—where the temperature increases with altitude. At such high temperatures, molecules like water vapor and titanium oxide and metals like sodium and potassium in the gas phase can be present in the atmosphere.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1635671