The 2017-2018 flu season is off to an early start, potentially hitting highs during the end-of-year holidays. Data so far suggests it could be a doozy. The predominant virus currently circulating tends to cause more cases of severe disease and death than other seasonal varieties. And the batch of vaccines for this year have some notable weaknesses.

To help you prepare—or just help you brush up on your flu facts—here are answers to every critical flu question you might ever have (well, hopefully). We’ll start off with the basics…

Table of Contents

What is the flu?

The flu, or influenza, is a contagious respiratory infection caused by the influenza virus (not to be confused with Haemophilus influenzae, an opportunistic bacterium that can cause secondary infections following sicknesses, such as the flu). Symptoms of the flu include chills, fever, headache, malaise, running nose, sore throat, coughing, tiredness, and muscle aches.

A little history: the flu virus gets its name from an Italian folk word that attributed colds, coughs, and fevers to the influence of the stars or astrological events. The term later evolved into to influenza di freddo, or “influence of the cold.”

Why does flu strike in the winter each year, anyway?

Though flu viruses circulate all year long, they do spike in the cold of winter. And it’s still not completely understood why. That said, researchers hypothesize that this spike is due to both changes in human behaviors and some biology. As the temperature outside drops, people tend to spend more time indoors with windows closed. There, they may be more likely to breathe in germy air and encounter sick people. Also, experiments in guinea pigs have shown that airborne flu viruses get around best when conditions are cold and dry—aka wintery.

This is just the seasonal flu we’re talking about. It’s not that big of a deal, right?

It is, actually. Seasonal flu epidemics cause three to five million cases of severe disease each year worldwide, leaving 300,000 to 500,000 dead, according to the World Health Organization. In the US, flu forces 140,000 to 710,000 people into hospitals and causes 12,000 to 56,000 deaths annually. The hardest hit are children, the elderly, and people with compromised immune systems.

In general, how long is a person sick and contagious?

Flu virus sickens and kills by getting into our airways and storming cells in the lining of our respiratory tracts. The virus forces its way into cells, usurps cellular machinery to make copies of itself, and the resulting clone army explodes out of the cell to march forth to the next cellular victims.

After quietly running amok for one to four days (the incubation period), symptoms begin. In healthy adults, it usually takes three to seven days to shake the infection. But, people can be infectious from a day prior to showing symptoms to five to seven days after symptoms clear.

Some flu viruses are worse than others, right? So, what are the different types of flu virus and what’s up with all those numbers and letters?

Flu viruses are in the Orthomyxoviridae family of viruses, which uses RNA as its genetic code (as opposed to DNA). The family includes four types of influenza that differ by the structural proteins that form their viral particles and support their RNA. The types are simply dubbed: A, B, C, and D.

Influenza A and B are the big ones; both cause seasonal epidemics. Type A viruses are particularly dangerous because they can infect humans, several other mammals, and birds—and jump between them. They easily morph and shift into new genetic forms, making them incredibly difficult to defeat. Type A viruses are responsible for flu pandemics. Influenza B viruses, on the other hand, only infect humans and seals. With their relative lack of host-hopping, type Bs shows less genetic transformations and have not been linked to pandemics.

Influenza C viruses infect humans, dogs, and pigs, and they have caused local outbreaks. But C viruses are currently not on a seasonal rotation. Influenza D viruses are relatively new to the family, first identified in the US in 2014. They infect cattle and pigs, but have not been seen in people.

With their genetic shifting and switching, Type A flu viruses are further broken down by the types of antigens they carry—those are molecular components that can trigger our immune systems to recognize an invader and mount a defense. These antigens are hemagglutinin (Ha or H) and Neuraminidase (NA or N). These are the basis for virus names like H1N1 and H3N2. There are 18 subtypes of Hs and 11 subtypes of Ns, creating the possibility of 198 different combinations.

But wait, there’s more. Variations exist within each type of virus and even within each subtype of H and N, creating even more types of flu.

To keep it all straight, the WHO came up with a system in 1979 to officially name each flu virus. Here’s how the rules say to list the name:

- type of virus (A, B, C);

- the animal origin (pig, bird, etc., but no designation for human);

- the location where it was isolated (e.g., Iowa);

- the strain number;

- the year of isolation; and

- if it’s a type A virus, the H and N numbers.

So official flu designations end up looking like this: “A/duck/Alberta/35/76 (H1N1)” and “B/Brisbane/60/2008.”

I hear about the Hs and Ns the most. Why are they so important?

Yes!!! I’m so glad you asked. Let’s talk about viral invasion!

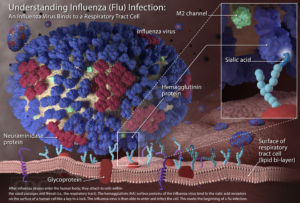

Both H and N are so important because they are critical for infection—and how we defeat the virus.

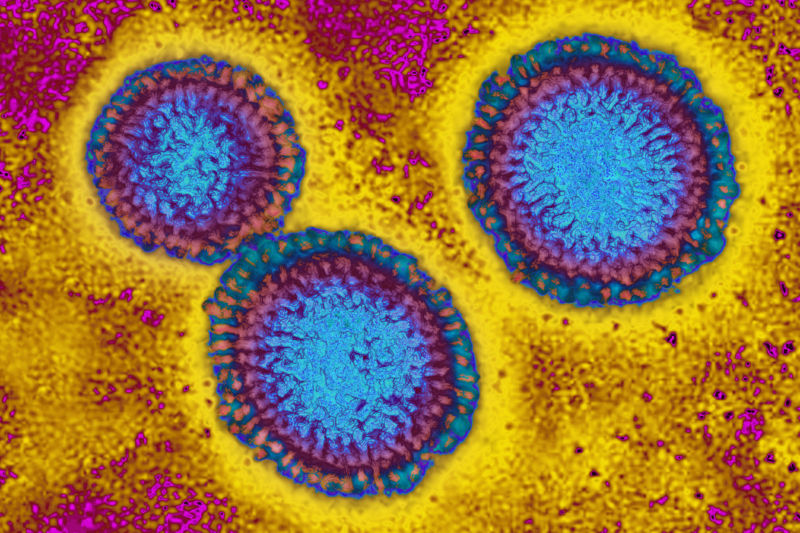

Both proteins are stuck onto the outside of the viral particles, forming little spikes that are visible under electron microscopes. Generally, H is responsible for getting the viral particle into a host cell where it can run amok. N is responsible for getting viruses out to go forth and invade more cells.

H works by grabbing onto a common sugar component of proteins that hang on cell surfaces, called sialic acid. Once attached, the viral particle gets essentially engulfed by the cell, a process called endocytosis. The cell creates a little membrane-bound bubble around the virus and then sucks it into the cell with the intention of destroying it.

Inside the now intra-cellular bubble, the pH is lower than outside of the cell. This environment triggers H to go through conformational shifts, creating longer projections that can pierce the bubble’s membrane. In other words, Hs coating the outside of the surrounded virus act like spring-loaded spikes that burst out, piercing and fusing to the membrane. This allows the virus to take over. (Pretty badass, right?)

From there, the virus can unload its contents into the cell, replicate its RNA using the cell’s replication machinery, and then start mass producing virus. When it’s time to move on, the viruses N can cleave the sialic acids on the host cell’s membrane, basically allowing the newly formed viruses to bud out.

Thus H and N are crucial to the viral invasions—but they can also be the source of their downfall. Because H and N prominently stick out from the surface of the virus, they provide a molecular signature that the immune system can use to spot the viruses—remember, I mentioned they were antigens. The immune system generates antibodies—little Y-shaped proteins—that recognize and block H and N and ignite responses that isolate and destroy the virus. That said, the antibodies that stick onto the tops of Hs are the most effective at defeating the viruses.

To get around these effective immune responses and move around to new hosts, type A viruses can morph their Hs and Ns easily. They can be dramatic changes, like swapping or making major changes to Hs, resulting in a virus changing from H0N1 to H1N1, for instance. Such big changes can create brand-new dangerous combinations and even spark pandemics. Or, there can be smaller genetic tweaks that create variation within an H subtype that can trip up immune responses and thwart vaccines.

Cut to the chase: What’s up with this year’s flu season?

According to the latest data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published Thursday (December 7), the flu season is off to an early start. Flu cases tend to crest between December and February. This year, weekly surveillance suggests it may peak at the end of December. Reports of flu have picked up recently and are expected to continue to increase in the coming weeks.

-

When flu visits exceed baseline (the gray line), it’s a sign of the start of the flu season.

-

A breakdown of what viruses are turning up this year so far.

The predominant viruses circulating are type A H3N2 viruses. H3 flu seasons tend to be nastier than others. To a lesser extent, surveillance has picked up another type A, H1N1, and a type B in the Yamagata lineage (lineages are used for type B viruses, instead of the Hs and Ns). This largely matches what experts predicted for this flu season.