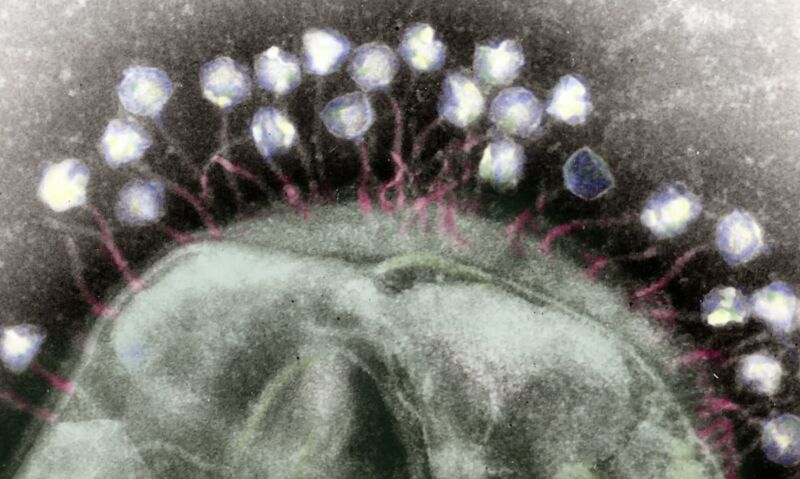

Every living thing on the planet plays host to viruses, and bacteria are no exception. Bacteriophages—or just “phages” to those in the know—are the viruses that attack bacteria. And we are in dire need of things that attack bacteria, since many pathogenic bacterial species have developed resistance to the antibiotics we’ve thrown at them for decades.

Phage therapy is attractive not only because antibiotic use yields antibiotic resistance but also because the treatment can be targeted specifically to the bacteria causing an infection. Most antibiotics in use are rather broad-spectrum, so they obliterate many of the bacteria they encounter, including the ones that are happily residing in our guts, minding their own business and not causing anyone any problems. Phages can be more precise.

But is phage therapy effective? A new study suggests it may end up being undercut by our own immune systems, which treat the therapies like a hostile invader.

Case studies

One promising case study that makes phage therapy look promising is provided by a 15-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis. He had a nasty bacterial infection, which was successfully treated with a cocktail of three different phages. But he was on immunosuppressants because he had just had a lung transplant. Phage therapy in immunocompetent people has not yet been as thoroughly examined, so we don’t really know how our immune system would deal with it.

The researchers who treated the boy learned of an 81-year-old man with lung disease who was infected with a closely related strain of bacteria. He had been treated with different antibiotic regimens for five years to no avail. The researchers took bacteria he coughed up and exposed it to the same three phages they had successfully used to treat the other patient, and they found that the phages killed most, but not all, of the bacteria. The bacteria the phages didn’t kill evolved some resistance to the phages, but none of the bacteria that survived were resistant to all three phages.

The researchers put the man on a six-month regimen of IV phage therapy but did not discontinue his antibiotics. There were no serious side effects. After the first month, things looked great; the amount of bacteria in his sputum dropped tenfold. But then they rebounded with a vengeance. At the end of the six months, his bacterial load was even higher than when he began. Phage therapy was discontinued.

Neutralized

Phage resistance did not account for this bacterial explosion; neutralizing antibodies against the phage did. Before the treatment, the patient had no such antibodies. But within a month of treatments starting, he developed antibodies of all subtypes against all three phages. The phages do not share many features, so there was not just one antibody cross-reacting with all of them—different antibodies were independently generated against each of them.

This does not mean that phage therapy is too good to be true; it just still may be in the “better in theory than in practice” stage of clinical development. We’ll need more than a couple of individual patients to understand the scope of the challenge.

Now that we know antibodies can interfere with phages, perhaps administering them serially might be better than giving them all together. Or maybe different phages will ultimately be used for immunosuppressed and immunocompetent people. Like antibiotics, phages are not a miracle cure. They have therapeutic utility, but it is not limitless.

Nature Medicine, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-021-01403-9. (About DOIs).

Listing image by Lawrence Berkeley Lab

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1779508