One of the most enduring mysteries within archaeology revolves around the identity of Punt, an otherworldly “land of plenty” revered by the ancient Egyptians. Punt had it all—fragrant myrrh and frankincense, precious electrum (a mixed alloy of gold and silver) and malachite, and coveted leopard skins, among other exotic luxury goods.

Despite being a trading partner for over a millennium, the ancient Egyptians never disclosed Punt’s exact whereabouts except for vague descriptions of voyages along what’s now the Red Sea. That could mean anywhere from southern Sudan to Somalia and even Yemen.

Now, according to a recent paper published in the journal eLife, Punt may have been the same as another legendary port city in modern-day Eritrea, known as Adulis by the Romans. The conclusion comes from a genetic analysis of a baboon that was mummified during ancient Egypt’s Late Period (around 800 and 500 BCE). The genetics indicate the animal originated close to where Adulis would be known to come into existence centuries later.

Many mentions, few details

The earliest known direct references to Punt come from the Palmero Stone, one fragment among seven others comprising an inscribed tablet that contained the royal annals of ancient Egyptian dynasties, from the earliest to the middle of the Fifth Dynasty. By the stone’s account, the reign of King Sahure around 2450 BCE saw a very profitable expedition to Punt: around 80,000 measures of myrrh, 6,000 measures of electrum, and equally as much timber and slaves.

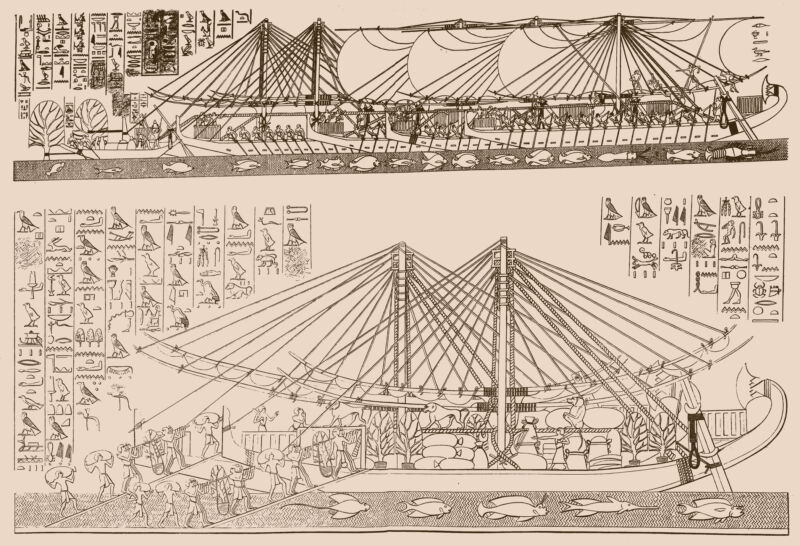

The most detailed depictions of Punt come from a mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahari dedicated to Queen Hatshepsut, the first female ruler to declare themselves pharaoh. Commissioned sometime in 1493 BCE, Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt was considered politically and religiously significant, as the ancient Egyptians apparently had lost their connection to the “God’s Land” over the centuries. Stone reliefs illustrate the expedition with scenes of Hatshepsut’s flotilla of ships arriving at a mysterious land, a village of beehive-shaped houses on stilts, all sorts of exotic flora and fauna (including myrrh trees and baboons), and the successful voyage back.

After Hatshepsut, the last known expedition to Punt occurred during the 12th century BCE under Ramses II, commonly known as Ramses the Great. A surviving papyrus describes the sailing of ships bearing cargo potentially down the Red Sea to Punt. But, like all other historical references, it makes no exact mention of how long these voyages took or where the ancient Egyptians went.

Despite the lack of precise directions, archaeologists have long entertained theories on Punt’s locale, said Josef Wegner, a professor of Egyptology and Egyptian archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the new eLife paper.

“Probably by the early 1900s and much of the 20th century, a lot of people would say that Punt was in the Horn of Africa. Somalia was frequently identified as Punt to the point where, sometime in the country’s history, the northernmost province of Somalia was actually named Puntland,” said Wegner. “There was also a debate whether it was both sides of the Red Sea. I think the prevalent opinion in Egyptology has been on the African side of the Red Sea from roughly the coastal areas of Sudan and modern Port Sudan all the way down to Eritrea and the northernmost point of Ethiopia.”

DNA evidence

In 2020, a team of researchers led by Nathaniel Dominy, an anthropologist at Dartmouth College, examined radioactive isotopes of strontium and oxygen in the mummified remains of baboons dating back to the New Kingdom (1550 to 1069 BCE) and the Ptolemaic period (305 to 330 BCE). Mapping the isotopic signatures to their approximate geographies, Dominy and his colleagues discovered some of the animals weren’t native to Egypt, likely hailing from somewhere in the area of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Somalia.

“The strontium values, for example, like in your molar teeth, reflect where you were when you were five, six, or seven years old. You move around as an adult and you live in different places but you retain that sort of fingerprint of your early childhood in a particular region,” said Dominy. “This was a cool project because we were able to show that some of those baboons spent their entire lives in Egypt, but others we could tell came from some distant place.”

Since we know Egyptians obtained baboons from Punt, this helped narrow the location slightly. And it provided some leads for Gisela Kopp, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Konstanz in Germany. In the new paper, her team, which included Dominy, analyzed the mitochondrial DNA of a mummified baboon first excavated in 1905 in Egypt’s Valley of the Monkeys located at Luxor’s western bank of the Nile River.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1982985