The first flight of Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket seems to have a payload. Instead of launching a sports car, as SpaceX did with its first Falcon Heavy rocket, Jeff Bezos’s space company will likely launch a pair of Mars probes for NASA.

NASA is aware of the risk of launching a real science mission on the first flight of a new rocket. But this mission, known by the acronym ESCAPADE, is relatively low cost. The Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers mission has a budget of approximately $79 million, significantly less than any mission NASA has sent to Mars in recent history.

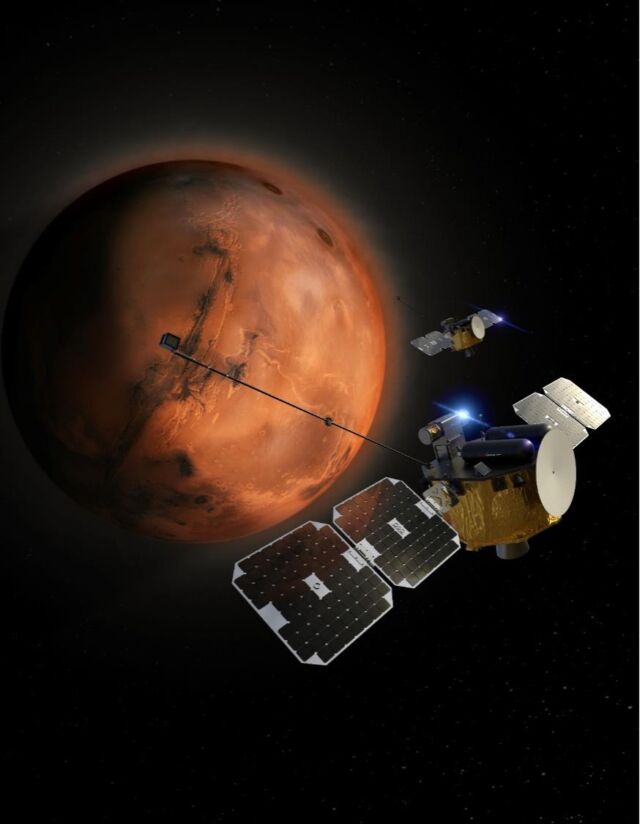

This mission will use two spacecraft to measure plasma and magnetic fields around the red planet. With simultaneous observations from two locations around Mars, scientists hope to learn more about the processes that strip away atoms from the magnetosphere and upper atmosphere, which drive Martian climate change.

ESCAPADE is part of a new class of small planetary science missions in which scientists can propose concepts for modest probes to explore the solar system. The relatively low cost of these missions allows NASA to accept some additional risk. The agency wouldn’t be comfortable putting a billion-dollar Mars mission on any unproven rocket.

Bradley Smith, director of launch services at NASA, said Monday that the ESCAPADE mission will “very likely be the very first launch of New Glenn.” He told a NASA advisory committee that this would be an “incredible ambitious launch for New Glenn.”

Taking a chance

Because it’s going to Mars, ESCAPADE has a relatively narrow window to get off the ground next year. Documents on the mission presented at public meetings earlier this year indicated it had a launch window in August 2024, but Smith said Monday that the mission is now set to fly “around this time next year.”

Rob Lillis, the mission’s principal investigator from the University of California Berkeley’s Space Science Laboratory, wrote on social media in April that the August 2024 launch window is “approximate and provisional.” He said engineers were still working on different trajectory options for ESCAPADE. Those options range from deploying the satellites into an orbit around Earth, then using their own propulsion to head for Mars, or a launch directly to the red planet.

The heavy-lift New Glenn rocket should have more than enough capability to send the two ESCAPADE satellites, each a little more than a half-ton in mass, on a direct-to-Mars trajectory. Ars asked Lillis and a NASA spokesperson this week for an update on the trajectory, but neither offered any new details. A Blue Origin spokesperson did not respond to questions from Ars.

Mars launch windows typically come every 26 months, so if ESCAPADE isn’t off the ground in late 2024, the next launch opportunity would be in late 2026. ESCAPADE was originally assigned to launch as a secondary payload on a Falcon Heavy rocket with NASA’s Psyche asteroid mission, which took off in October, but NASA removed ESCAPADE from the launch because it would not provide the mission with the proper trajectory.

Since then, engineers redesigned the ESCAPADE mission to take advantage of a larger spacecraft platform built by Rocket Lab, which provides additional propulsive capability. In February, NASA announced the launch contract with Blue Origin for ESCAPADE to fly on one of the early New Glenn missions. Now, this Mars mission has moved up in the queue to be first in line on the New Glenn manifest.

The first launch of Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket was originally scheduled for 2020, but it’s now running four years late. The New Glenn will be Blue Origin’s first orbital-class rocket, and it’s a big one, with a height of more than 320 feet (98 meters) and a 23-foot-diameter (7-meter) payload fairing, larger than any other currently operational rocket.

The rocket can lift nearly 100,000 pounds (45 metric tons) of payload into low-Earth orbit, according to Blue Origin. This is a weight class above the uppermost capability of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket or SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket but below SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy.

NASA says it got a good deal from Blue Origin on the ESCAPADE launch contract. Procurement documents suggest the deal is worth $20 million, a price tag that Smith said reflects the risk of launching on the first flight of a new rocket.

But there’s not just the risk of a failed launch. Given Blue Origin’s history of delays, it’s fair to question whether New Glenn will really be ready to fly in a year’s time. The company’s launch pad at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida is complete, and production of rocket parts is underway at Blue Origin factory a few miles away.

But Blue Origin hasn’t rolled a full-scale New Glenn rocket out to the launch pad for testing, including propellant loading and countdown rehearsals. These first-time launch pad tests have run for several months to more than a year for other rockets, such as SpaceX’s Starship, ULA’s Vulcan, or Europe’s Ariane 6.

“There’s certainly some schedule risk associated with New Glenn getting to the pad a year from now,” Smith said. “They’re building hardware … I’ve seen their schedule. I’m not going to put a percentage out there.”

NASA contracted the launch with Blue Origin through a venture-class procurement initiative, which usually works with smaller rockets like Rocket Lab’s Electron or Firefly’s Alpha.

“As a trade-off of taking a little more risk on an unproven rocket, your deliverables are a little bit different, and your confidence in making a call to your customer about when you’re ready to go fly is a little bit diminished,” Smith said.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1986091