Swimmer’s ear happens when constant exposure to cold water irritates tissues in the ear canal, causing bony growths to form. As its name implies, it commonly shows up in people who spend a lot of time in the water. But it also shows up in almost half of Neanderthal skulls from Eurasia, according to a recent study.

Washington University paleoanthropologist Erik Trinkaus and his colleagues studied fossils, digital scans, photographs, and other archaeologists’ reports from 77 Neanderthals and Homo sapiens who lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene. Based on this sampling of remains with preserved inner ear bones, a surprising number of Neanderthals were running around Pleistocene Eurasia with swimmer’s ear.

Lifestyles of the cold, damp, and windy

You won’t get swimmer’s ear from a single cold-water surfing trip. It takes long-term exposure to cold water or cold, damp air for the irritation to actually reshape the bone. If you’re looking at a skeleton, swimmer’s ear is the kind of trait that can tell you something about a person’s habits in life. Anthropologists still aren’t exactly sure what swimmer’s ear tells us about Neanderthals’ lifestyle, but it may have something to do with genetics, hygiene, and a taste for shellfish.

Based on Prof. Trinkaus and his colleagues’ sample of fossilized skulls, it looks like Pleistocene Homo sapiens were more or less as likely to suffer from swimmer’s ear as modern people—but maybe a little more likely than you’d expect for people living in colder inland areas.

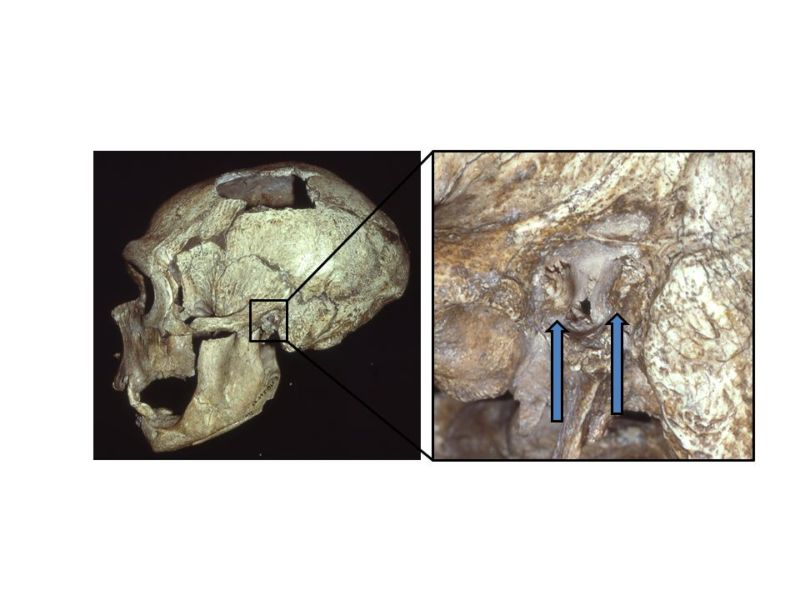

Meanwhile, Neanderthals seem more than twice as likely to suffer swimmer’s ear (about 48%). And they were more likely to develop severe cases, with bony growths large enough to mostly block the ear canal, as in the elderly Neanderthal now known to us only as Shanidar I. If the sample gives us an accurate picture of the whole Neanderthal population, then Neanderthals apparently suffered from swimmer’s ear more often than just about any group alive today except people from the Canary Islands and the coast of Southern Brazil.

Since swimmer’s ear is the result of habits and activity, those differences should tell us something about how Neanderthals lived—and how their lifestyles differed from their Homo sapiens neighbors. In particular, it looks (at first glance) as if Neanderthals must have spent much more time in, on, or near the water. Based on archaeological evidence and traces of chemical isotopes preserved in fossil bones, researchers can look for other clues to try to explain what Neanderthals were doing to get so much water in their ears.

Gone fishin’?

“Aquatic foraging is most likely,” Trinkaus told Ars. If you lived in Eurasia during the glacial advances and retreats of the Middle and Upper Pleistocene, you probably wouldn’t have played in the water much; temperatures were much colder than today at most sites (although for some areas, scientists don’t yet know exactly how much colder). Finding food is a compelling reason to risk a dunking.

Ratios of certain chemical isotopes in bones and teeth can reveal what kinds of food a person generally ate, and of course bones and shells at archaeological sites offer great clues. There’s not much evidence to paint Neanderthals as huge consumers of fish, shellfish, and other aquatic foodstuffs, though—not to the extent that should make them likely to be spending excessive amounts of time with cold water.

That’s especially true at sites far from the coast. Isotope analysis of 29 inland Neanderthals found little trace of freshwater vertebrates like fish or frogs. There’s some evidence of connections here and there, though. At Spy Cave, two Neanderthals showed signs of swimmer’s ear, and a skull from the same cave had grains of waterlily starch in the fossilized plaque on its teeth.

There’s more evidence of coastal Neanderthals eating seafood. Isotope ratios in fossil bones suggest that Neanderthals ate fish in Western Europe, mollusks along the Mediterranean and Iberian coasts, and marine mammals and crustaceans in western Iberia. But even that evidence doesn’t always line up with where Trinkaus and his colleagues found Neanderthals with signs of swimmer’s ear.

And at Tabun Cave, a Neanderthal woman with a moderate case of swimmer’s ear lived at a site with no archaeological traces of coastal foods. But further north along the Mediterranean coast, mollusks do show up at other sites from the same period. So it’s possible that the same was true at Tabun, but the evidence just didn’t survive tens of thousands of years.

Prof. Trinkaus and his colleagues suggest that the evidence of swimmer’s ear may fill in a gap in the other two lines of evidence. This suggests that Neanderthals looked to rivers, lakes, and streams as sources of food more often than modern researchers assume. If that’s correct, it may mean that foraging was equal-opportunity work in the Pleistocene, because males and females in the sample were equally likely to have swimmer’s ear (and that was true of both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens). The female sample was pretty small, however, so there’s probably not enough information to say for sure.

More than one explanation

On the other hand, no evidence so far suggests that Neanderthals ate fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants more often than Homo sapiens. So unless Neanderthals were simply a lot more prone to falling into the water, foraging habits alone aren’t enough to account for the huge difference in swimmer’s ear.

Trinkaus and his colleagues say that the apparent epidemic of swimmer’s ear among Neanderthals probably had multiple explanations. One could be basic hygiene, although it’s hard to imagine Homo sapiens of the time were actually much better at cleaning out their ears. “They all had relatively unsanitary living conditions,” Trinkaus told Ars.

Another possibility is a difference in genetic susceptibility. In modern human populations, some people are more prone to swimmer’s ear than others. It mostly has to do with how sensitive the ear canal’s blood vessels are to cold water, which appears to be a genetic trait. (This is based on experiments in rats and on the fact that people who participate in the same water sports often end up with different degrees of swimmer’s ear.)

That’s an individual trait, though; it doesn’t tend to be any more common in one group of people than another. But if Neanderthal populations, for some reason, had a higher rate of susceptible people than their Homo sapiens neighbors, that could help explain the difference.

For the moment, anthropologists don’t have enough evidence to fully explain why swimmer’s ear affected around half of Eurasian Neanderthals. But at least now we know that it did.

PLOS ONE, 2019. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone/0220464 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1553569