This June, the world will mark the 55th anniversary of the first woman flying into space. Valentina Tereshkova, an amateur Russian skydiver, spent nearly three days in orbit inside a spherical Vostok 6 capsule. The first American woman, physicist Sally Ride, would not follow Tereshkova into space for another two decades.

A new documentary on Netflix, Mercury 13, examines the question of why NASA did not fly women in space early on and, in particular, focuses on 13 women who underwent preliminary screening processes in 1960 and 1961 to determine their suitability as astronauts. The film offers a clear verdict for why women were excluded from NASA in the space agency’s early days—”good old-fashioned prejudice,” as one of the participants said. Mercury 13 will be released Friday.

The film admirably brings some of these women to life, all of whom were accomplished pilots. There is Jerrie Cobb, who scored very highly in the preliminary tests and gave compelling testimony before Congress in an attempt to open NASA’s early spaceflight programs to women. Another key figure is pilot Jane B. Hart, married to a US Senator from Michigan, whose experience in the project compelled her to become one of the founders of the National Organization for Women.

Chilling chauvinism

There certainly is ample evidence within Mercury 13 to back up its central conclusion. A particularly chilling moment arises with Gordon Cooper, one of NASA’s Mercury 7 astronauts and the sixth American to fly into space. During a 1960s news conference, a male reporter asks Cooper, “The Russians have put up a woman cosmonaut. Is there any room in our space program for a woman astronaut, in your opinion?”

In his response, Cooper appears to reference an earlier flight, the 1961 Mercury-Atlas 5 mission that tested the orbital capabilities of the Mercury spacecraft before John Glenn’s orbital flight in early 1962. In this test flight, NASA flew Enos, a chimpanzee, who survived. “Well, we could have used a woman on the second orbital Mercury Atlas that we had,” Cooper answered. “We could have put a woman up, the same type of woman, and flown her instead of the chimpanzee.” Cooper and the reporters then laughed.

These, and other similar though less jaw-dropping comments, are revelatory of the kind of discrimination women had to deal with then and, in some regrettable ways, must still contend with today. (For more good insight into how the male astronauts treated Sally Ride and her female colleagues when they first came to NASA in 1978, astronaut Mike Mullane’s book Riding Rockets offers an honest assessment of his own chauvinism.)

Mercury 13 concludes with an excellent point—that had men and women landed on the Moon in the 1960s, the Apollo program would not just have proven a feat of technical engineering but a true watershed moment for equality of the sexes. Had women walked on the Moon, perhaps some young girls in schools today would not feel inferior in math classes to their male counterparts.

A counterpoint

With that said, the film has a few problems. It portrays Dr. Randy Lovelace, a NASA scientist who had conducted the official Mercury program physicals for the men, as a hero. And certainly he was ahead of his time in thinking that women were just as capable as the men and that they belonged in some of the earliest US spaceflights.

After his experience with NASA’s Mercury program, Lovelace devised a three-part testing process for 25 women: five days of medical testing in New Mexico, psychological tests in Oklahoma including a sensory-deprivation chamber, and then finally flight tests at the US Navy’s Pensacola, Florida, flight training center.

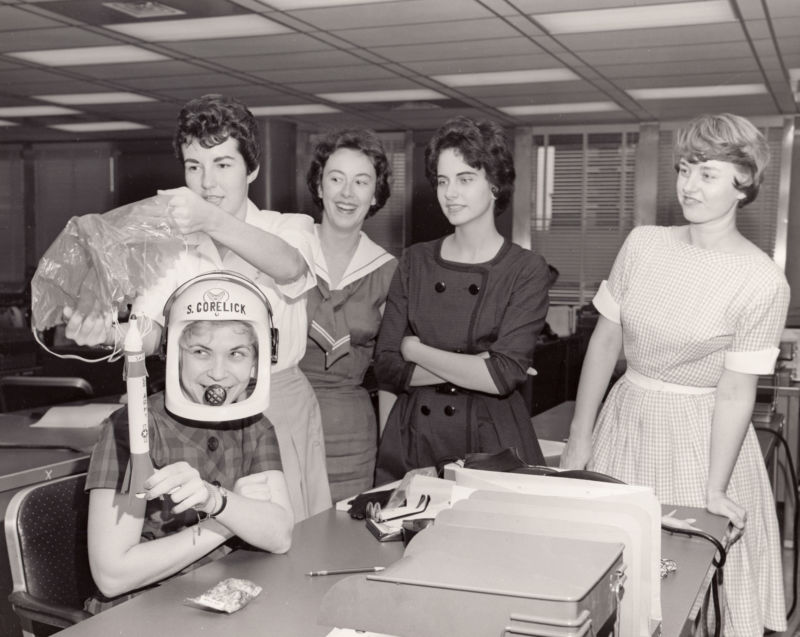

Thirteen women—hence the film’s title, Mercury 13—passed the medical screenings. But the flight tests never happened, because when US Navy officials in Pensacola asked Dr. Lovelace for the name of his government sponsor, he didn’t have one. He had been operating the “First Lady Astronaut Trainees” program entirely outside the purview of NASA and without the agency’s official sanction. It would have been helpful to understand whether the skilled pilots who underwent these tests felt duped by Lovelace or at least learn what exactly he had represented to the women trainees.

Mercury 13 could also have done with a more thorough examination of why NASA didn’t seek to include women in its early program or take over Lovelace’s program after he had found 13 skilled pilots who met the same medical standards as the Mercury 7 astronauts. I do not dispute the film’s conclusion that the men running the US government and NASA preferred to keep US spaceflight a “boys’ club.” But some of these men are still alive today, and it would have rounded out the film to get their perspective.

NASA redeemed

From a historical perspective, Tereshkova’s flight, although groundbreaking in its achievement, is probably more properly regarded as a stunt. She was not a pilot and evidently flew primarily for propaganda reasons rather than to bring women into the regular Russian corps. Of the more than 120 cosmonauts who have flown into space, just four have been women. Yes, the Russians flew a woman into space first, but this was certainly not a moment of lasting gender parity.

Meanwhile, since getting a lamentably late start, NASA has taken significant steps in this regard. The space agency has flown 45 women into space and, of its last two astronaut classes (2013 and 2017), nine of the 20 astronaut candidates were women.

More than that, women have begun to take prominent roles in spaceflight. The home of NASA’s astronaut corps, Johnson Space Center, has been directed by Ellen Ochoa since 2012. And last year, Peggy Whitson, who has flown into space three times, broke the record for most time spent in space by a US astronaut, with a cumulative total of 665 days in orbit aboard the International Space Station. Nearly six decades after the events in Mercury 13, US women aren’t just flying—they’re helping to lead.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1293791