I’ve got a history with Internet scammers. I’ve spent hours on the phone with tech support scammers, and I’ve hunted down bot networks spreading fake news. But for some reason, I’ve lately become a magnet for an entirely different sort of scammer—a kind that uses social media platforms to run large-scale wire-fraud scams and other confidence games. Based on anecdotal evidence, Twitter has become their favorite platform for luring in suckers.

Recently, Twitter’s security team has been tracking a large amount of fraudulent activity coming out of Africa, including “romance schemes”—wherein the fraudster uses an emotional appeal of friendship or promised romance to lure a victim into a scam. Thousands of accounts involved in the ongoing campaign have been suspended. But that has hardly put a dent in the efforts of scammers, who move on to set up new accounts and run new scams. And there are dozens of other fraud games being played out on Twitter and other platforms.

I’ve been gathering anecdotal data from a number of such accounts as they’ve attempted to prepare me for a lure. They follow a fairly easy-to-spot pattern for anyone who has tracked identity scams. But the scale of these efforts goes far beyond what you’d expect from what are (to those in the know) recognizable cons. This suggests that there’s a high level of sophistication to this latest wave of fakers.

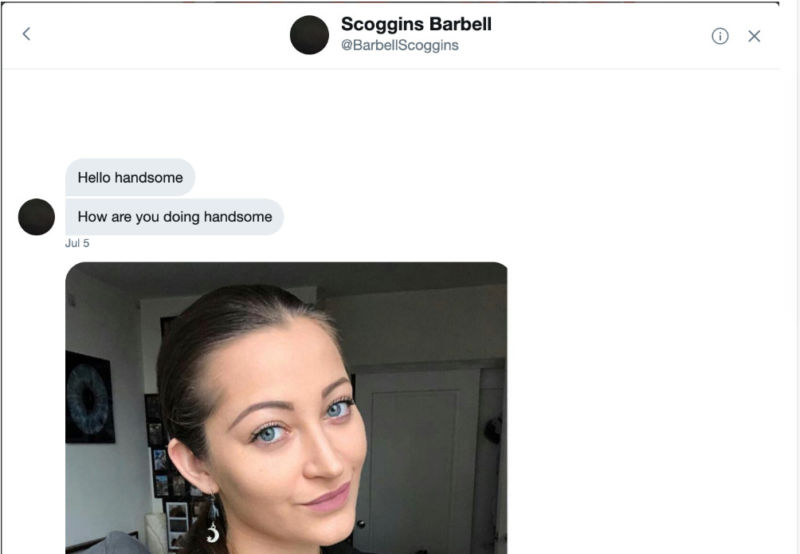

Finding these accounts wasn’t hard. I get about three direct message requests per week that start off with a simple “hi” or the more come-hither “hi honey.” Sometimes, these messages are from individual accounts (or maybe groups) who claim to be women who “just want to chat and make friends.” Often, these are slow-moving affairs—probably because the people on the other end are involved in trying to reel in multiple fish.

Catfishing for profit

The approach used by the fraudster varies with the target. Although flirting is more common, others are more direct. In one case, a woman was contacted in direct messages on Twitter by an account claiming to be a retired carpenter from Tennessee looking to draw her in with the promise of a “sugar daddy” relationship that quickly revealed itself to be an Amazon gift-card scam.

Social media has long allowed people to portray themselves as someone else. While we’ve reported heavily over the past few years about “bots” and other fake accounts used to spread misinformation, the deception often goes much deeper than just putting on a particular political mask—as demonstrated by the 2010 documentary Catfish. And the potential malicious uses of faked social media profiles were somewhat controversially demonstrated by Robin Casey and Thomas Ryan’s “Robin Sage” experiment in December of 2009, using photos of an actress from a pornography website to create a profile for a fictional Navy “cyber threat analyst.”

According to “her” profiles, “Robin Sage” was 25 years old and an MIT graduate with more than 10 years of work experience in the cybers (meaning she had been in the game since the tender age of 15). She garnered more than 300 Facebook “friends” and LinkedIn connections across the defense and information security communities, got offers to do consulting work at Google and Lockheed Martin, and received a number of dinner invitations. “Sage” was also given access to personal data on military personnel and senior executives that could have been leveraged for ill intent.

The Twitter accounts that act as the front end for the scams currently being tracked by Twitter and other platforms are not so nuanced. But they apparently do well enough to support a very large-scale operation. They follow the same MO as “Robin Sage:” harvesting images from various social media and Web sources to create a persona that is believable to the type of victims they stalk—gullible men and women susceptible to flattery from an apparently attractive stranger in need.

The accounts sometimes use the same name as the person from whom they’ve harvested images. Other times, they use some variant of it to throw off people who might do some surface-level investigating, making it look like they’ve just set up a secondary account. I confronted one scammer up front by asking if they were actually the person behind the account the image was from—and they responded that that account had been set up by their “ex-husband.”

“Not 100 percent to anyone”

-

And so it begins.

-

She’s totally a model.

-

There appears to be a language barrier in Michigan.

-

A compelling immigrant story?

-

“Am not 100 percent for anyone.” So true.

-

Sharing stolen pics.

-

I come clean, but will “she”?

-

I can’t take the deception anymore.

-

Blocking is such sweet sorrow.

For fake female accounts, adult video stars are a favorite source of profile photos among scammers. But “influencers” (models with a heavy Instagram presence) and “lifestyle bloggers” are also good sources, as their social media streams are full of selfies and images tailored to be intimate. A quick check with Google’s image search will often turn up the source or other accounts that have used the same stolen image, or both. The images used by the “divorced woman” above were harvested from an Orange County, California-based lifestyle and “mommy” video blogger’s social media accounts.

Typically, the scammers will claim to be from obscure but relatable places—places that their targets would likely not know much about—or to be deployed overseas in the military. In the case above, “she” claimed to be from Michigan and, when pressed for more details, said she was originally from “Newcastle UK.” “She” could not provide coherent details about either location. When I expressed doubt about “her” actual location, “she” replied, “Am not here to be 100 percent to anyone.”

I threw a Bit.ly link to a website I controlled into the chat. “She” clicked it, revealing that the user behind the account was in Nigeria.

These fake accounts have limited numbers of social media posts—mostly a few of their stolen photos and retweets from other, seemingly random accounts. They have few followers—often, many of their followers are other scam accounts. I found the followers of one account that approached me included accounts using stolen images associated with a number of previous Instagram romance scams. The accounts they follow are either targets, scam accounts, or random accounts related to a particular identity “theme.”

NFL + BBC

For example, one account of a “woman” who approached me followed gun-related accounts (including Maj Toure’s Black Guns Matter), National Football League-related accounts, and “BBC” porn-related things (and I’m not referring to the British Broadcasting Corporation). “She” also followed a number of potential victims, including an accountant in Saskatoon. Among her follower was an account that was using images stolen from the Instagram account of a Marine veteran and personal fitness coach from California.

Often, the scammers will attempt to move the target off Twitter to another “secure” communications channel that reveals more personal information. “Rose” responded to a comment I made about Nigerian scammers by trying immediately to steer our interaction to Hangouts or WhatsApp.

I coaxed a WhatsApp number out of “Rose.” The number she provided was a US number obtained through a “disposable” SMS number service, and my attempt to locate “her” with a tracker showed she was using a US-based Web proxy—pretty good operational security for a scammer.

Unfortunately, “Rose” noticed I was live-tweeting our interactions and pulled the plug before we could get to the scam itself. In fact, I’ve had a really hard time keeping in character in interactions with all of the scammers I dealt with, mostly because I found staying credulous about their claims to be nigh impossible.

Other people have retained their credulity, to ill effect. There are whole blogs and Facebook groups full of people who have fallen for romance scams; one French man’s photos have been used in so many romance scams that a Facebook page has been set up just to track all of the scams using them. In June, the BBC reported that a woman from southeast Wales had been scammed out of 40,000 pounds (about $50,000 US) in payments to a single scammer.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1538567