NOAA released its monthly weather update Thursday, looking back at the fall and ahead through the rest of winter. As we close in on the (good riddance) end of 2020, its global temperature status is coming into focus. It’s looking like a bit of a coin flip between the year being the warmest or second warmest on record, depending on how you estimate the odds.

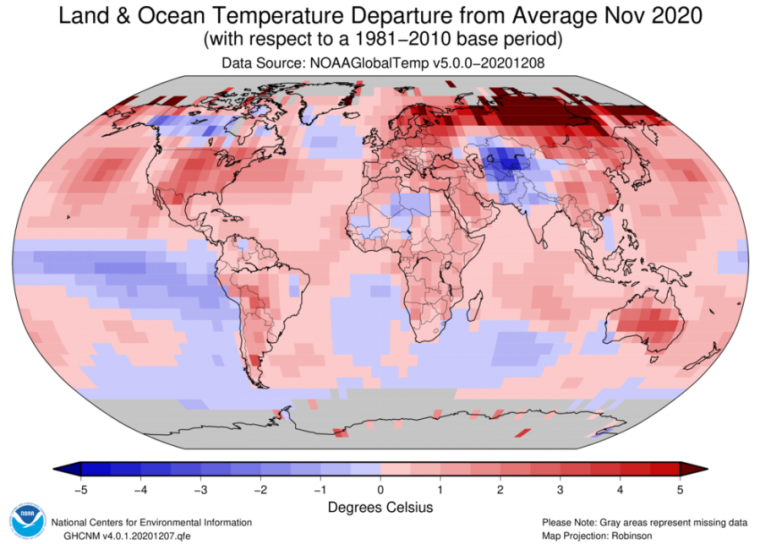

Globally, November was the second warmest on record, while the autumn period of September through November was the third warmest. The fact that this is true despite moderate La Niña conditions in the Pacific is notable, as those conditions bring cold, deep water up to the surface, which normally drags down the global average temperature.

At this point, 2020’s only competition for the warmest year on record is 2016, which was boosted by a strong El Niño. (That means more of the equatorial Pacific was covered by warm surface water.) The two years are so close that some datasets may even rank them in different order than others. NASA’s Gavin Schmidt, for example, estimates over 90 percent odds of setting a new record, but NOAA’s latest estimate is about 55 percent.

For the contiguous US, November was pretty consistently warmer than normal and dry. Specifically, it was the fourth warmest November on record and the 33rd driest. For the autumn season as a whole, it was the 11th warmest and only a little below average for precipitation—though that obscures a big east-west divide in rainfall.

No change in the weather

November’s weather was dominated by high pressure ridges across the US, which is why the weather pattern was so consistent. The only exception was the second week of the month, when a low pressure trough formed in the West. That brought cooler temperatures and some precipitation, particularly farther north. At the same time, the influence of Hurricane Eta produced rain in Florida and up the mid-Atlantic.

NOAA put a spotlight on Florida this month, where 2020 has so far been the warmest year on record. The state has been on a roll for about five years now, with 65 out of the last 68 months coming in above the long-term average—including the last 31 months straight. The last few years really stand out, as you can see in the chart below.

The trend in nighttime warming has been notably stronger than daytime warming, though that basic pattern is fairly common. As an example, this autumn saw 246 warm records set for daily high temperatures in Florida, but 687 records for warm daily lows. (There were just 19 new record cold daily lows.) Along with long-term warming driven by greenhouse gases, there are a few other factors that help explain this, Florida state climatologist David Zierden said. Combined with sea surface warming around Florida, humidity has trended upward, holding more heat in the air through the night.

Zooming back around, the widespread warm and dry weather pushed drought to cover an additional four percent of the US last month, putting fully 49 percent of the country in that category. A primary area of expansion was the Southeast, where La Niña conditions tend to keep things particularly dry.

-

November temperatures (note legend at bottom).

-

November precipitation.

-

Fall temperatures.

-

Fall precipitation.

-

Smoothing data by averaging 5 years at a time highlights the steep increase in recent years.

-

Over 49 percent of the US is now in a drought category.

Looking ahead

Speaking of La Niña, it is still expected to remain through the winter, but the spring forecast is edging back toward neutral (neither La Niña nor El Niño) conditions. By summer, neutral conditions are now favored.

Still, the outlook for the next few months is dominated by La Niña patterns. The January outlook generally tilts toward above-average temperatures, with the exception of the northwest US up through southeast Alaska. Due to the way the winter jet stream tends to set up during a La Niña, the southern tier of the US is likely to be dry, while much of the northern tier is likely to be wet. The Northern Plains region is an exception there, with equal chances of wetter or drier weather in the outlook.

The outlook for January through March is a stronger version of the same. Cooler temperatures may stretch into the Northern Plains from the Pacific Northwest, and so does the wetter outlook. The area of wetter weather pushes down from the Great Lakes into the Ohio Valley area, which is partly an expectation based on common storm tracks in the past.

All this means that drought is expected to grow across the Central Plains and Gulf region but continue to improve in the Pacific Northwest and in the Northeast.

-

January temperature outlook. Warm colors show odds favoring above-average, blue below-average, and white equal chances to go either way.

-

January precipitation outlook.

-

January-March temperature outlook.

-

January-March precipitation outlook.

-

US drought outlook through March.

-

January-March temperature outlook.

-

January-March precipitation outlook.

North of the border, the current Environment and Climate Change Canada two- to four-month outlook covers January to March. Above-average temperatures are favored in the far southeast, with below-normal temperatures most everywhere else. The precipitation outlook is patchy, with above-normal amounts favored from British Columbia into the Prairies, in the Great Lakes region, and parts of Eastern Canada.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1730756