Once renewable sources of electricity meet or beat the costs of fossil fuel generation, everything changes. With the immediate financial benefit just as clear as the long-term environmental benefit, utilities turn their attention to how to make it work rather than debating whether it’s worth the investment. Solar and onshore wind technologies have hit this point in recent years, but the unique challenges presented by offshore wind have required different solutions that have taken time to mature. Governments have provided some subsidies to encourage that progress, and global capacity grew to 28 gigawatts last year. But those subsidies make it trickier to calculate how close to cost-competitive offshore wind has become.

A team led by Imperial College London’s Malte Jansen worked to compare 41 offshore wind projects in Europe going back to 2005. The researchers’ analysis suggests offshore wind, at least in Europe, is on the cusp of dropping below the price of more traditional generating plants.

Subsidies and auctions

Bids for constructing these offshore wind farms came in through national auctions, which included subsidies with varying structures. They all offered guaranteed prices for the generated electricity. Some promise to pay the difference when the market rate drops below the guarantee while allowing the wind-farm operator to increase profits when the market rate rises above the guarantee. Others require the utility to return excess profits when the market rate is high. And each country has a different limit on how long the guarantees last, whether that’s a set number of years or a set amount of electricity sold.

Because of these differences, calculating the cost of offshore wind isn’t as simple as comparing new project bids to bids for, say, natural gas power plants. What’s more, detailed data on costs and revenue often aren’t available, as the bid is the only number made public.

To break this down, the researchers took each project’s public bid along with the rules of that country’s auction and calculated revenue against monthly market prices for a 25-year lifetime. That does require the use of projected future prices for electricity, but that’s true for traditional calculations for any power plant. At the end, they get an average cost of electricity from each offshore wind farm, as well as the total estimated subsidy. Subsidies are calculated two ways: one for the case where utilities are responsible for building grid infrastructure, and one where countries largely finance the grid.

Becoming priceless

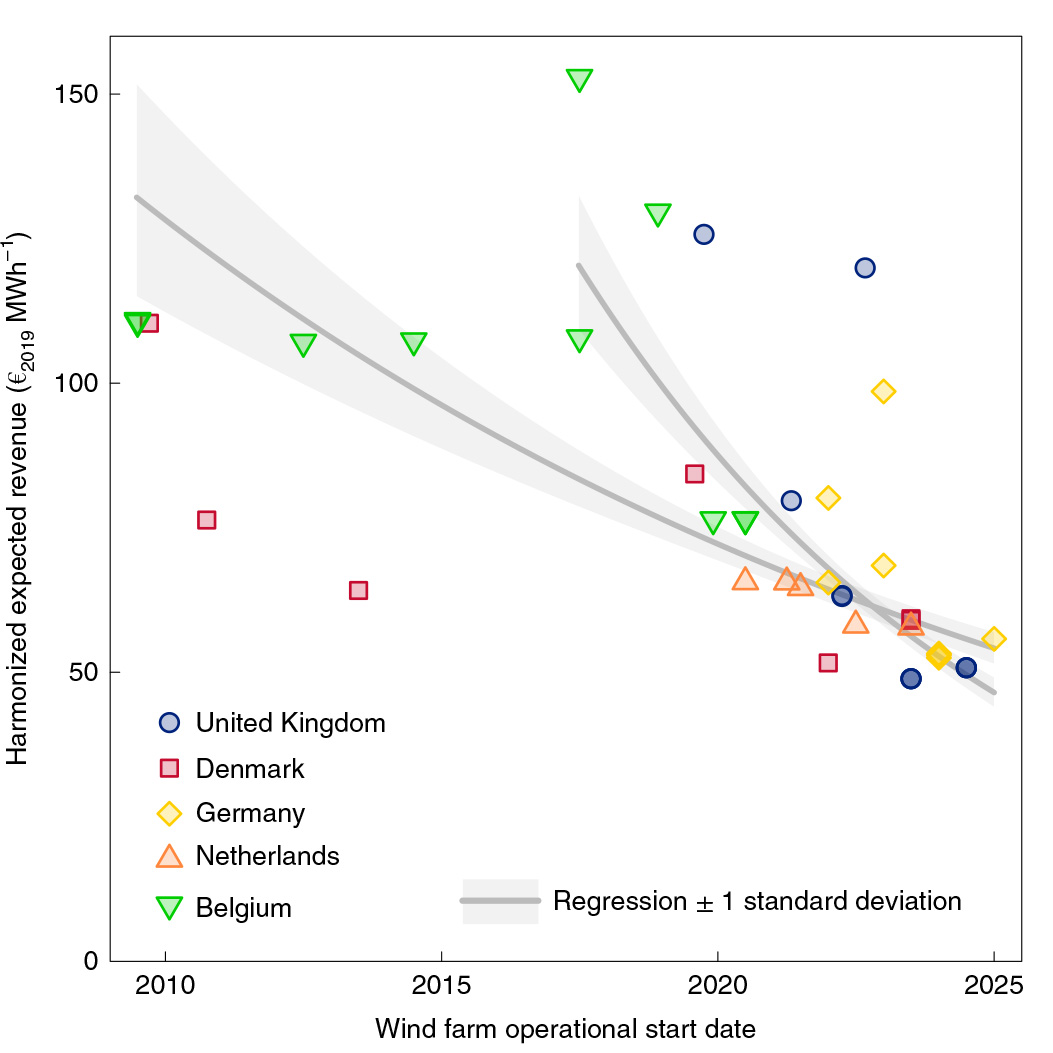

Bids to provide electricity in these auctions have ranged from €0 to €150 per megawatt-hour, with that value setting the minimum guaranteed price. The €0 bids came in recent auctions in Germany and the Netherlands, and they represent utilities that were confident in their unsubsidized revenue selling at wholesale market prices.

The researchers’ estimates for actual revenue at these wind farms came in at €50-150 per megawatt-hour. But the interesting thing is the downward trend over time—dropping about 6 percent per year over the whole time period, and more like 12 percent per year if you start with 2015. For wind farms that won’t start operating until after this year, the range drops to €50-70 per megawatt-hour. And €50, the researchers say, is at the “lower end of [cost] estimates for fossil fuel generators.”

That means subsidies have also been declining over time. In fact, the average is on track to hit zero by 2025. And if electricity prices rise at all in the coming years, a few wind farms that have already been bid will turn out to be subsidy-free in the final accounting. The researchers paint this as a success story.

“Policymakers can take the rapid price decreases shown here as evidence that offshore wind will deliver in the future as a low-cost and low-carbon technology. Hence, the initial spending made on support schemes has been successful in helping to create a new industry,” they write. “Building on the story of success, policymakers may want to extend their attention to support less mature technologies such as floating offshore wind, which would allow access to deeper waters with higher wind speeds. These technologies are currently at a less mature stage, but may prove vital in harnessing the world’s best wind resources.”

Nature Energy, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41560-020-0661-2 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1694599