Gold and certain other precious metals are key ingredients in computer chips, including those used in consumer electronics such as smart phones. But it can be difficult to recover and recycle those metals from electronic waste. Japanese researchers have found that a pigment widely used by artists called Prussian blue can extract gold and platinum-group metals from e-waste much more efficiently than conventional bio-based absorbents, according to a recent paper published in the journal Scientific Reports.

“The amount of gold contained in one ton of mobile phones is 300-400 grams, which is much higher by 10-80 times than that in one ton of natural ore,” the authors wrote. “The other elements have a similar situation. Consequently, the recovery of those precious elements from e-wastes is much more effective and efficient when compared to their collections from natural ore.”

Prussian blue is the first modern synthetic pigment. Granted, there was once a pigment known as Egyptian blue used in ancient Egypt for millennia; the Romans called it caeruleum. But after the Roman empire collapsed, the pigment wasn’t used much, and eventually the secret to how it was made was lost. (Scientists have since figured out how to recreate the process.) So before Prussian blue was discovered, painters had to use indigo dye, smalt, or the pricey ultramarine made from lapis lazuli for deep blue hues.

It’s believed that Prussian blue was first synthesized by accident by a Berlin paint maker named Johann Jacob Diesbach around 1706. Diesbach was trying to make a red pigment, which involved mixing potash, ferric sulfate, and dried cochineal. But the potash he used was apparently tainted with blood—one presumes from a cut finger or similar minor injury. The ensuing reaction created a distinctive blue-hued iron ferrocyanide, and eventually came to be called Prussian blue (or Berlin blue).

The earliest known painting to employ Prussian blue is currently Pieter van den Werff’s Entombment of Christ (1709), but the recipe was published in 1734, and Prussian blue was soon widespread among artists. Hokusai’s famous artwork, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, is among the most famous works to use the pigment, along with Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night and many of the paintings from Pablo Picasso’s “Blue period.”

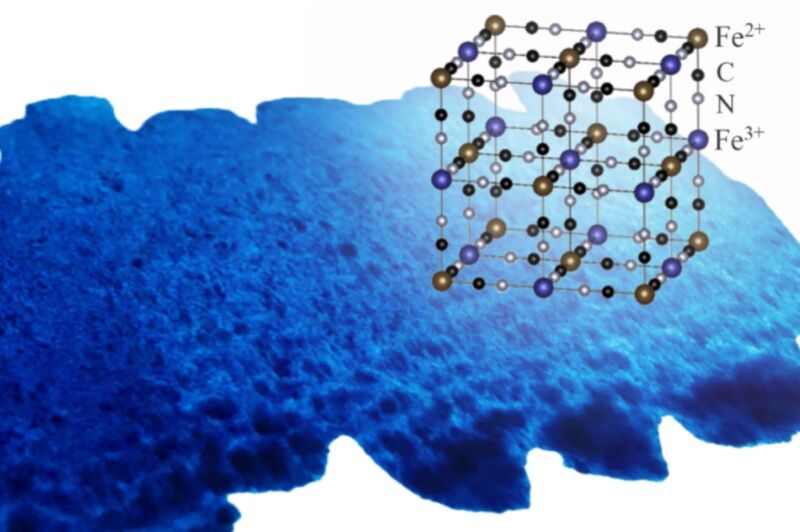

The pigment has other uses. It’s often used to treat heavy metal poisoning from thallium or radioactive cesium because its lattice-like network structure—similar to a jungle gym—can trap metal ions from those metals and prevent them from being absorbed by the body. Prussian blue helped remove cesium from the soil around the Fukushima power plant after the 2011 tsunami. Prussian blue nanoparticles are used in some cosmetics and it’s used by pathologists as a stain to detect iron in, for example, bone marrow biopsy specimens.

So it’s a very useful substance, which is why the Japanese authors of this latest paper decided to explore other potential practical applications. They analyzed how Prussian blue uptakes multi-valent metals—like platinum, ruthenium, rhodium, molybdenum, osmium, and palladium, among others—using x-ray and ultraviolet spectroscopy. They were surprised at how well the pigment retained its jungle-gym structure while substituting iron ions in the framework—the secret to its impressive uptake efficiency compared to bio-based absorbents. That’s great news for e-waste recycling.

Prussian blue could also solve one of the challenges of disposing of nuclear waste, according to the authors. Current practice involves converting radioactive liquid waste into a glass-like state at a reprocessing plant, prior to disposal. But platinum-group metals can accumulate on the walls of the melters, eventually causing an uneven distribution of heat. So the melters must be flushed after each use, which in turn increases costs. Prussian blue could remove those deposits with no need for flushing the melters after every use.

DOI: Scientific Reports, 2022. 10.1038/s41598-022-08838-1 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1861831