It would be hard to miss the rise of ransomware attacks given how visible some have been this year. With multiple state and local governments set back on their heels by ransomware—including the RobbinHood ransomware attack in May that the City of Baltimore is still recovering from, to the tune of $10 million in recovery costs and $8 million in lost revenue—ransomware attacks have become an almost daily part of the news. But these attacks against municipal and state governments are only the most high-profile part of a much larger trend, according to a report issued by IBM’s X-Force Incident Response and Intelligence Services (IRIS) today.

According to data from X-Force IRIS, the ransomware problem is part of a much larger overall increase in destructive malware attacks that has been spiking over the past six months. X-Force’s response to cases of destructive malware increased 200% between January to July 2019 in comparison to the previous six-month period.

“Of those destructive malware cases, 50% targeted organizations in the manufacturing industry,” the researchers noted. “Other sectors significantly affected included oil and gas and education. Most of the destructive attacks we have observed hit organizations in Europe, the United States, and the Middle East.”

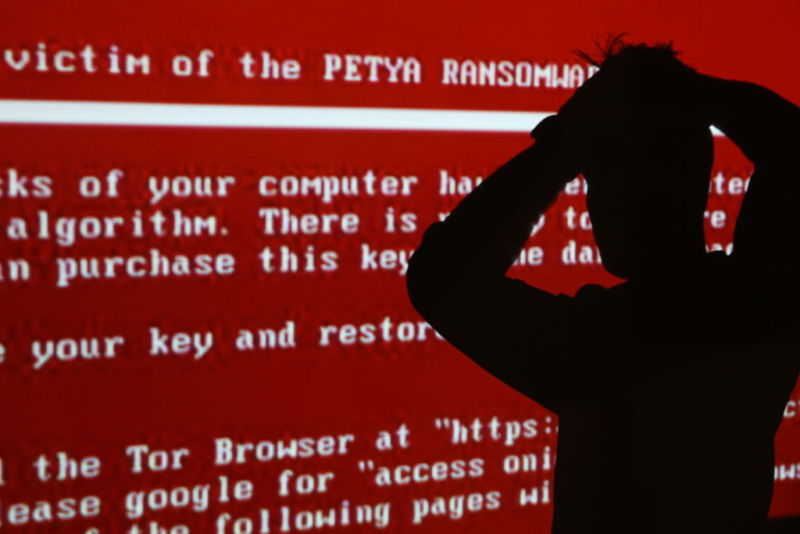

IRIS has witnessed ransomware attacks—criminal attacks where a ransom is demanded in exchange for a key—specifically increase by 116%. “While not all ransomware attacks incorporate destructive malware,” the IRIS team wrote, “the simultaneous increase in overall ransomware attacks and ransomware with destructive elements underscores the enhanced threat to corporations from ransomware capable of permanently wiping data.”

Going low

The line between ransomware and purely destructive malware has been blurred ever since the WannaCry and NotPetya attacks used ransomware-based attacks solely for destructive purposes. Ransomware itself can be considered destructive malware, since it renders data irretrievable if victims don’t pay for an encryption key. But there has also been a rise in the use of purely destructive attacks by cybercriminals—a type of attack usually associated with state-backed attackers in the past, such as the Iran-attributed Shamoon, the US-Israel-attributed Stuxnet (which actually destroyed hardware with malicious commands), and the North Korea-attributed Dark Seoul attacks.

“Wiper” capable ransomware like LockerGoga and MegaCortex still have a financial component, but these initiatives go after industrial systems as well as data. And attacks such as the GermanWiper malware use the same “faux ransomware” approach as NotPetya—they offer a key in exchange for a ransom but are irreversible. Additionally, the IRIS team noted that they had seen “financially motivated attackers switch to destructive tactics when they perceive they are not achieving their objective…using destruction as a means of revenge.”

“There are two forms of targeted attacks in the destructive world—’I need to be low and slow until I gather the information I need and plan out my attack,’ or ‘I’m going to drop in, release it, and let it go wild,'” as Christopher Scott, IBM X-Force IRIS’ Global Remediation Lead, put it. But the latter are not in the majority. IRIS observed attackers “reside” within targeted organizations’ networks for up to over four months before launching their destructive payloads—giving the malicious actors plenty of time to perform reconnaissance of the network and stealthily spread their access. And the attackers will go to great lengths to preserve access to key bits of infrastructure within the network throughout their intrusion, allowing them “to maintain control of their strongholds for as long as possible, and to cause as much damage as they can.”

This extended time on the network also gives defenders more time to detect the attacks before they move to the destructive climax. And finding and knocking out their points of access early can help prevent or reduce the blow of an attack in progress.

While some non-targeted ransomware attacks have exploited vulnerabilities in servers to gain access to their victims’ networks, the majority of targeted ransomware and destructive attacks begin either with a spear-phishing email, “credential stuffing” (guessing or outright brute-force attacks with passwords), “watering-hole” attacks (using a site related to a job or industry to spread malware, sometimes through malvertising or compromise of the website), or through some other compromise of a third-party system (such as a cloud service or software-as-a-service provider).

PowerShell scripts are still heavily used by ransomware attacks to spread across networks. But with PowerShell scripts increasingly being blocked by organizations on typical users’ systems, destructive attackers are more often targeting “privileged accounts”—those with administrative access across a wide range of systems. “Unlike attempting remote access, which can generate significant noise,” the X-Force IRIS report noted, “moving laterally with a privileged account can allow the adversary to stealthily move between devices while appearing to be legitimate administrative activity.”

In some cases that the IRIS team responded to, an attacker used administrative access to “wipe an organization’s entire email system,” making it even more difficult to respond to the attack.

Defensive measures

Preventing ransomware and destructive attacks outright would be the ideal solution, but it may not be realistically possible for many organizations—especially as more attacks come in from third-party networks. So instead, isolating the parts of network infrastructure that are affected is essential to limit the damage, the IRIS report noted.

“Even in cases where an attack materializes, if the affected parts of the infrastructure are isolated, an organization can significantly limit the damage and prevent some of the impact to its operations,” the team wrote. “Reducing the number of devices affected by a destructive attack can also drastically reduce the cost and time associated with reconstitution.” Isolating critical parts of network infrastructure from third-party networks is an important part of that—using multiple layers of security control and network defenses.

IRIS’ other advice to organizations includes running tests of response plans “under pressure” and using threat intelligence resources to get a better idea of the potential risks they face. But all of these seem like a lot to ask for some of the types of organizations that have been falling to ransomware. Nowadays, ransomware-targeted organizations are ones that fall below the information security poverty line in terms of administrative and security resources, have shallow IT expertise internally, and can’t even manage to train users on potential threats from phishing attacks.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1546117