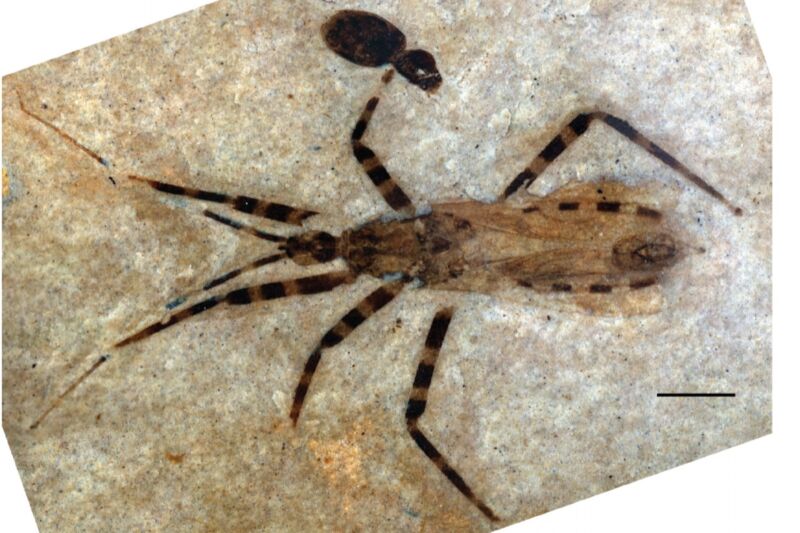

A rare fossilized assassin bug is causing a bit of a stir in entomology circles, because it is so remarkably well-preserved that one can distinctly pick out its penis. The specimen dates back 50 million years to the Eocene epoch, meaning this particular taxonomic group may be twice as old as scientists previously assumed. The University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) researchers who conducted the analysis described their unusual find in a new paper published in the Journal of Paleontology.

“Getting a complete fossilized insect is really rare, but getting a fossil of an insect from this long ago, that has this much detail, is pretty amazing and exciting,” Gwen Pearson of Purdue University’s Department of Entomology, who is not a co-author on the paper, told Ars. Assassin bugs (part of the Reduviidae family, of the order Hemiptera) are predators favored by gardeners because they eat pests. The mouth is distinctly shaped like a straw, the better to poke into the body of its prey, like a juice box, and slurp out the guts.

But of course, it’s the preserved genitalia that make this fossilized specimen so exciting. The genitalia are contained within a shell—Ruth Schuster, writing at Haaretz, described the penis (technically its “pygophore”) of the assassin bug as a “chitinous codpiece”—which is why it’s difficult to tell whether a given insect specimen is male or female. In addition to the pygophore and the telltale stripes on the legs, the new fossil also distinctly shows the “basal plate,” a structure shaped like a stirrup that supports the penis.

“The thing that makes bug penises so interesting is that in many cases they are part of the exoskeleton,” said Pearson. “It’s not because entomologists are pervy, it’s because genitals are the place where we can see evolution happening. That’s where the sexual selection is strongest. And the more we know about how insects lived and diversified in the past, that helps us understand how they’re living and diversifying now.”

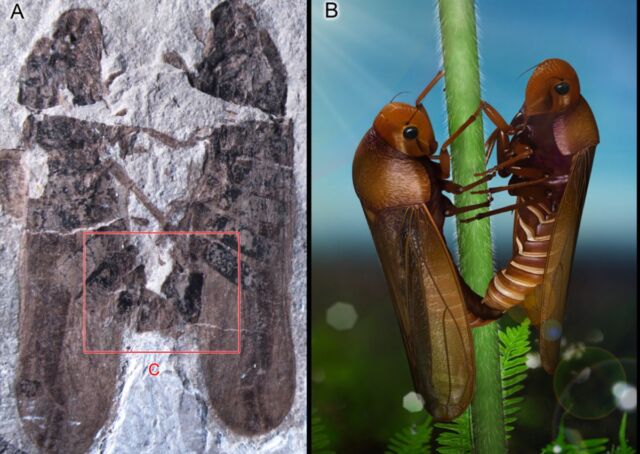

Among other rare ancient insect finds is the 2013 discovery of a fossilized pair of insects in a related taxonomic group known as froghoppers (Anthoscytina perpetua), caught in flagrante delicto, their copulation preserved in great detail for over 165 million years. The froghoppers were so well-preserved in a belly-to-belly mating position, one can see the male inserting its “aedeagus” (analogous to the penis) into the female’s “bursa copulatrix.”

Most insect fossils are found in a few dozen “jackpot” deposits known as konzentrat Lagerstätten, loosely translated as “a deposit where a whole bunch of fossils were preserved,” per a new article in Entomology Today. Those fossil-rich regions include the Green River Formation, a series of sedimentary deposits located in what is now Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. That’s where this new fossil was found in 2006, near Meeker in Rio Blanco County in Colorado, by a fossil collector named Dan Judd. The ancient bug has been dubbed Aphelicophontes danjuddi in his honor.

Another unusual feature is that the specimen split neatly in half in the field when Judd found it, instead of one half encasing the actual fossil and the other recording its impression, which is what usually happens. “The Green River shales are very well-laminated and split nicely like the pages of a book,” co-author Sam W. Heads, a paleontologist at UIUC, told Ars. “I expect Mr. Judd will have given the stone a tap or two with a hammer and popped it open, revealing the specimen inside. It was pure luck that it split the way it did right through the coronal plane. I did do a little minor preparation in the lab with a very fine pin mounted in a pin vice, just to remove some matrix that was covering certain parts of the body. Other than that, the specimen was perfect.”

-

The two halves of the fossilized assassin bug.D.R. Swanson et al., 2021

-

Schematic diagram labeling the body partsD.R. Swanson et al., 2021

-

Close-up view and schematics of the fossilized genitaliaD.R. Swanson et al., 2021

-

Excised genitalia from a representative sample of modern assassin bugsD.R. Swanson et al., 2021

When Heads first received one half of the specimen, he “was awed by the wonderful preservation including the beautifully preserved color pattern,” he said. “I immediately recognized it as an assassin bug and was simply ecstatic about it since they are not common in the fossil record. I ran straight into my colleague’s office next door to mine to show him the specimen.”

Upon closer examination under the microscope, he realized that the internal genitalia were also very well preserved—cause for even more excitement. “I didn’t sleep much that night,” Heads admitted. Within a week, he learned that Judd was willing to donate his half of the specimen, thereby enabling Heads and lead author Daniel Swanson, Heads’ graduate student, to learn even more about the bug’s morphology. “I had another jump-for-joy moment as I examined it and found that the genitalia were visible on that half also and not only that, but it preserved slightly different parts of the phallic complex,” he said. “I realized we might be able to reconstruct the morphology of the phallus of this insect.”

Much of the paper focuses on tracing out, in precise detail, the various tiny details of this particular specimen to make the case for the final species assignation. Heads and Swanson also soaked the butts—excuse me, “caudal ends”—of a representative sample of modern assassin bugs in water, so they could easily remove the genitals with forceps. When they compared those genitals to the fossilized sample, they were a match. This provides “strong evidence that the genitalia were similar in the group, and were probably under similar selective pressures for the past 50 million years,” the authors concluded.

According to Pearson, despite being around for so long, fossilized insects from millions of years ago have the same basic body plan as their modern counterparts. “The pieces that change [over the course of evolution] are the tiny squidgy bits,” she said. “So much of what we know about insects and how we classify them is about their genitals, because each species will very often have distinct bits that only fit in their species.”

Heads said that this new fossil belongs to a branch of a family tree typically dated back 25 million years. Since this fossil dates back 50 million years, it’s possible one branch of assassin bugs diversified earlier than previously believed.

Swanson is now completing work for his PhD, which includes compiling a detailed review and catalog of all known fossil assassin bugs, fixing a few taxonomic errors made by other scientists in the past for good measure. According to Heads, among the most important potential implications of Aphelicophontes will be its use in calibrating molecular phylogenetic analyses of the entire Reduviidae.

“This is like reconstructing the family history or genealogy of the group, determining how the various genera and species are related to one another,” he said. “Fossils like Aphelicophontes are extremely valuable in this kind of work because they provide us with a minimum age for a particular lineage, which informs estimates of divergence times and can provide important data about the acquisition of different morphological characters through time.”

In addition, “Aphelicophontes tells us something about the paleoecology of the ancient Green River Formation paleobiota,” Heads said. “Assassin bugs are important predators in terrestrial ecosystems, so it’s useful to know that they were there as part of the ancient insect fauna.”

DOI: Journal of Paleontology, 2021. 10.1002/spp2.1349 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1739301