Rarely has the future of Earth’s climate felt as malleable as it does this week. While substantive climate legislation morphs behind the scenes of the US Congress, nations have gathered in Glasgow to improve on their Paris Agreement pledges. Pledges, of course, require follow-through before they become reality, and it can be difficult to judge how encouraging each announcement is.

So how about a look backward instead of forward? The newly released global carbon budget report for 2021—an annual release from a huge group of scientists under the banner of the Global Carbon Project—actually includes a downward revision of total human-caused CO2 emissions for the last few years. Probably.

What have we done?

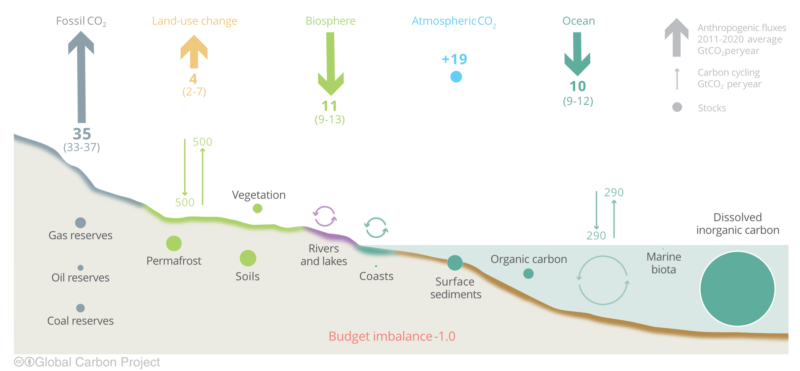

This annual publication includes our best estimates of each contributor to the Earth’s carbon cycle. That includes human-caused emissions but also uptake by land ecosystems and the oceans. Fossil fuel burning isn’t too hard to quantify, but the other elements are. Emissions from agriculture and deforestation—or conversely, uptake by reforestation—take more work and are therefore less certain. And estimates of the total amount of atmospheric carbon sequestered on land and in the oceans rely on models running with whatever observations we can feed them. But this whole-system perspective is crucial to understanding the consequences of our emissions.

Let’s start with the latest fossil fuel numbers (which also include cement production). As a result of the pandemic, 2020 global CO2 emissions fell almost 5.5 percent from the previous year. That number included growth of over 1 percent in China, declines of about 11 percent in the US and EU, and declines of about 7 percent in India and the rest of the world.

Preliminary estimates for 2021 show a nearly complete recovery, despite hopes that economic stimulus packages would leverage cleaner development. These numbers put China up 5.5 percent over 2019 emissions, India up almost 4.5 percent, and the US, EU, and the rest of the world each around 4 percent below their 2019 marks.

The good news comes from the estimated emissions due to land-use change, primarily forestry. This estimate relies on three data sets that have given fairly disparate answers over the last decade or so. Updated methods used to populate those data sets have brought all three much closer together in that timeframe, and the result is that estimated emissions for the last decade are lower.

Since these numbers are added to fossil fuel and cement emissions to tally total human-caused CO2 emissions, that means the totals for the last decade are also reduced a bit. In particular, the last decade is flattened, with 2015, 2018, and 2019 nearly equal at the top. Most notably, estimated 2019 emissions were revised down from 43.1 billion tons of CO2 to 40.5 billion tons.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1810554