Robinhood’s move to temporarily limit purchases of GameStop and other highly volatile stocks in late January was the overwhelming focus of today’s House Committee on Financial Services hearing.

At the hearing, Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev said that extreme stock volatility that led to Robinhood’s restriction was a “five sigma” event with a “1 in 3.5 million” chance of happening. That made the situation practically impossible for the company to plan for, Tenev said. “In the context of tens of thousands of days in the history of US stock market, a 1 in 3.5 million event is basically unmodelable.”

As we’ve covered previously, the high volatility of GameStop and other so-called “meme stocks” last month meant Robinhood was suddenly forced to provide much more collateral to the stock clearing houses that actually process its trades. Tenev said Thursday that these collateral obligations increased tenfold between January 25 and January 28, as GameStop rose from $76 a share to over $347, then back down to $193.

“Despite unprecedented conditions, what happened is unacceptable to us,” Tenev said. “To our customers, I’m sorry, and I apologize. We’re doing everything in our power to make sure this won’t happen again.”

Where’s the money?

Tenev reiterated multiple times that Robinhood never had a liquidity issue in terms of covering its users’ actual positions. But the company did lack immediate capital to cover those collateral requirements, which meant its only alternative was to temporarily limit sales of those stocks until it could raise more funds (or until the stocks became less volatile).

Some members of the House Financial Services Committee were not impressed with that quibbling over what “liquidity” means for Robinhood. “Your customers wanted to buy the stock,” Rep. Van Taylor (R-Texas) said at one point. “You wouldn’t let them do it because you didn’t have the capital to allow them to do it.”

Tenev was also taken to task for not clearly and quickly communicating the reasons behind those restrictions to customers. Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.) noted that Robinhood’s initial January 28 blog post announcing the restrictions contained “no disclosures about capital requirements” and only “vague language about restricting trading.” The initial impression, she implied, was that Robinhood was “[making] up the rules as you go along.”

Since it was forced to halt trading, Robinhood has attracted over $3.4 billion in additional investment that Tenev said “cushions the firm from market volatility and further black swan events.” And while he was apologetic, Tenev also said that “other firms did similar things in restricting buying [of these volatile stocks], which suggests it is a systemic problem rather than a uniquely Robinhood problem.”

But Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) pointed out that “when Robinhood prohibited it customers from purchasing additional shares of certain stocks, other brokerages merely adjusted margin requirements on these stocks.” That, she suggests, might mean that “the issue isn’t clearinghouses but that you simply didn’t manage your own margin rules or failed to manage your own internal risks.”

Some on the committee also focused on Robinhood’s business model, which generates a majority of its revenue by selling its “order flow” to market makers like Citadel (who then shave a little bit of profit off of the price improvement they can provide over the exchanges). “When you’re not paying for it, it’s not free,” Rep. Brad Sherman (D-Calif.) said regarding Robinhood’s commission-free trades. “You’re the product, someone else [i.e., Citadel] is the customer.”

“If removing revenues from payment for order-flow would cause the removal of commission-free trade, doesn’t that mean trading on Robinhood isn’t actually free to begin with, because you’re just hiding the cost?” Ocasio-Cortez added in some pointed questioning.

Deregulate or re-regulate?

While Tenev was apologetic for the mistakes Robinhood made, he also placed some blame on what he called outdated and moribund trade settlement rules that place a lot of pressure on the system. Under the current T+2 timeline for stock settlement, market makers actually have two full days to officially settle a trade (i.e., transfer the shares/cash) after it’s made. When a stock’s price is especially volatile, the clearinghouse needs more collateral to cover the potential price changes that could happen on either side of the trade in that two-day interval.

“The existing two-day period to settle trade exposes investors and the industry to unnecessary risk,” Tenev said. “There is no reason why the greatest financial system in the world can not settle trades in real time…. If we had real-time settlement capability and infrastructure was modernized, we wouldn’t have seen similar problems.”

Ken Griffin, CEO of Citadel, stopped short of asking for real-time trade settlement in his testimony to the committee. But he said that relaxing the rules to a one-day turnaround would “reduce counter-party risk holistically.” While instant or same-day clearing of trades would be nice, Griffin said it would essentially require “all systems… to function at all times every day with no room for error.”

Rep. Andy Barr (R-Ky.) pointed out through his questioning that the current capital requirements were put in place in 2010’s Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform bill. “If anyone has a problem with [Robinhood]’s decision, their frustration should be with federal regulations,” he said. Rep. William Timmons (R-S.C.) added that Dodd-Frank is “arguably to blame for this exorbitant capital requirement that you weren’t able to meet… Well-intentioned legislation is somewhat responsible.”

Other House members, like Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) argued forcefully for a 0.1 percent financial transactions tax, which would discourage speculative betting on meme stocks and limit algorithm-driven high-frequency trading. She noted that Hong Kong implemented a financial transactions tax that’s twice as large, limiting high-frequency trading without hurting that market’s significant growth.

But Jennifer Schulp, director of Financial Regulation Studies at the free-market-focused Cato Institute, told the committee such taxes “often fail to raise money and distort trading in a way that’s unforeseen. A financial-transaction tax might seem like a small imposition, but it often hurts individual investors’ long-term goals by affecting institutions that do the trading.”

While Schulp allowed that a financial-transactions tax might decrease total volatility in the market, she added that she doesn’t think it would have had that effect in the particular case of GameStop’s recent stock moves, which were driven primarily by heavy buying.

Diamond hands

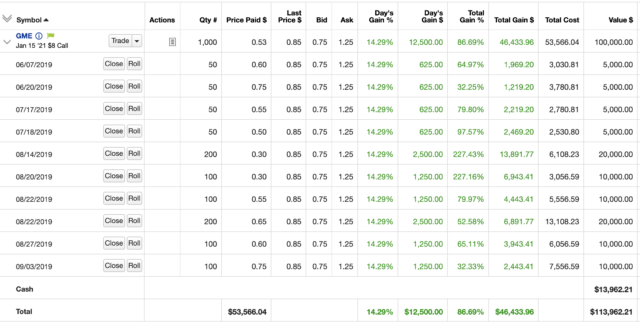

To represent the retail traders who helped drive the GameStop bubble, the committee heard from Keith Gill, aka DeepFuckingValue on Reddit. He first invested in GameStop in mid-2019 (when the stock was valued at under $10) and heavily hyped the stock’s value on the WallStreetBets subreddit. “The market was underestimating the prospects of GameStop’s legacy business and overestimating the risks of bankruptcy,” he said. “I grew up playing video games and shopping at GameStop, and I plan to keep shopping there. GameStop stores provide real value to gamers and real revenue to GameStop.”

Gill, who has now made millions off an initial investment of about $50,000, said he still thinks GameStop is an attractive investment at its current price of about $40 a share. His optimism is thanks in large part to GameStop’s potential to pivot to a more focused e-commerce strategy. “As for me, I like the stock,” he said. “I’m as bullish as I’ve ever been on a potential turnaround, and I remain invested in the company.”

Less represented at the hearing were the many other investors who bought into the stock at or near its peak in late January, only to see their investments crumble in days. Rep. Jim Himes (D-Conn.) brought up the case of Salvador Vergara, who took out a $20,000 personal loan to invest in GameStop only to see his stock’s value go down 80 percent in days. “We need to be thoughtful about this,” Himes said, regarding how to deal with retail investors’ access to the market.

The committee also heard from Reddit co-founder and CEO Steve Huffman, who said Reddit had found no evidence of bots or foreign agents playing a significant role in trying to unduly pump up any stock through the WallStreetBets subreddit. “We will comply with requests from regulators, but we believe the community was well within bounds of our own policies,” he said.

“It’s a real community,” Huffman continued, regarding WallStreetBets. “The self-deprecating jokes, memes, and crass at times language reflect that. There’s a significant depth to the community based on the affinity users show for each other.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1743729