Rocket Lab said Thursday it will attempt to recover the first stage of its Electron rocket for the first time with its next mission, scheduled for liftoff in mid-November.

This step follows a series of tests during which Rocket Lab has been building toward a full stage recovery. During these earlier tests, engineers have deployed parachutes from the first stage at maximum loads and collected data as two earlier rockets returned through “the wall,” which is what the company calls the high heat and pressure of reentry at supersonic velocity.

The company’s founder, Peter Beck, said during a conference call with reporters that he was not sure what the company would fish out of the ocean. It could be a nearly intact first stage or, he admitted, “a smoldering stump.” The key with this test, he said, was to gather data about the parachute system.

Beck announced the company’s plans to begin using its small Electron rocket a little more than a year ago, saying the goal was to effectively double production of the vehicle in the face of customer demand. “We’re seeing the production delivery times get smaller, and a stage is rolling out of the factory every 30 days now,” he said. “But really, we’re just nowhere close to keeping up with the demand from our customers.”

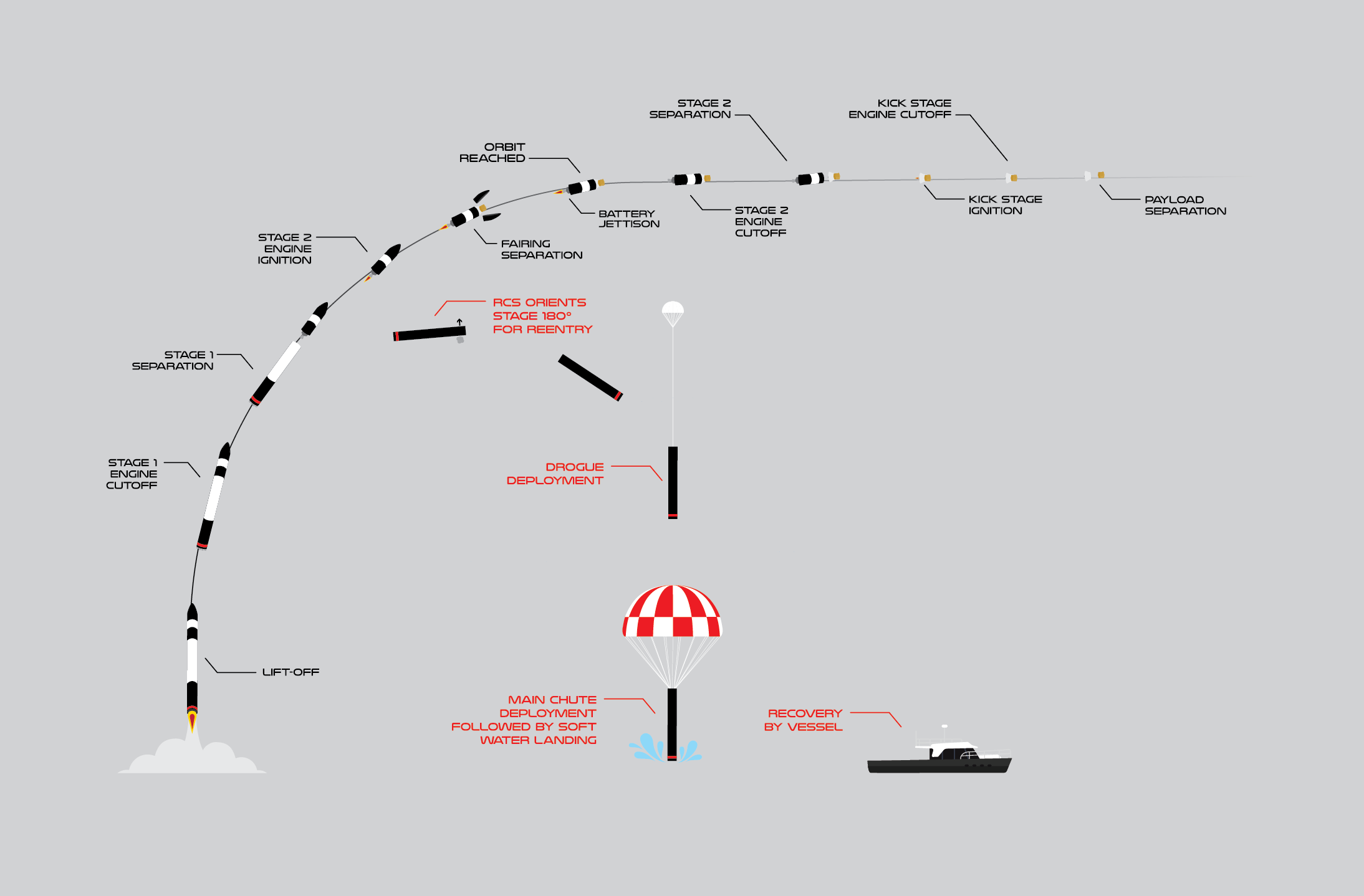

His engineers developed a plan whereby the first stage would launch and separate from the Electron second stage, as normal, at an altitude of 80km and then use reaction control system thrusters to reorient the vehicle for reentry, with the engine section leading the way. Unlike with SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, the nine first-stage engines on Electron will not fire. (SpaceX is the only company to successfully recover a first stage.)

As the Electron rocket descends lower into the atmosphere, a drogue parachute will deploy, followed by a main parachute. If all goes well, the rocket should splash into the ocean traveling less than 10 meters per second.

That is the plan, at least. With the upcoming mission, named “Return to Sender,” the company will then recover the vehicle from the ocean and return it to its factory in New Zealand to see what condition the first stage is in.

“Parachutes are not trivial things to get right,” Beck said. “Whenever you throw out a piece of fabric at just slightly under the speed of sound, it’s always a little bit interesting. I’ll stop being nervous once we get it back in the factory.”

The company will likely have to fine-tune Electron’s hardware and software, Beck said, and this should improve future recovery efforts. Once the company is able to bring the first stage back whole, the final step will be catching the vehicle mid-air, using a helicopter—this will avoid water damage to the vehicle from the ocean. The company has already successfully practiced this maneuver by capturing a mock rocket stage with a helicopter.

“I’m sure there’s going to be a ton of work on heat shields and on various bits and pieces that we’ll need to get right,” he said. “When we’ve reached the point where we have something that’s in a condition that we actually care that it doesn’t get wet, we’ll start bringing the helicopter in.”

This may take several flights, but the company has plenty of commercial missions upon which to test this technology. Beck said the cost to Electron’s payload capacity to incorporate a parachute, heat shielding, reaction control systems, and other measures is only about 15 kilograms.

The “Return to Sender” mission will deliver 30 small satellites into various orbits, and the two-week launch window opens on November 15. The down-range recovery attempt will take place about 400km from the launch site, in the Pacific Ocean.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1719581