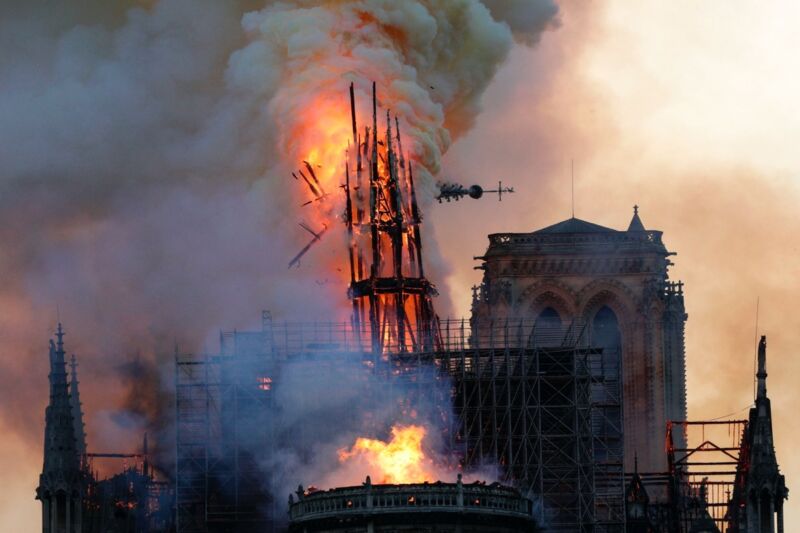

On April 15, 2019, the world watched in horror as the roof of the famed Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris caught fire. The blaze spread rapidly, and for several nail-biting hours, it seemed this 850-year-old Gothic masterpiece might be destroyed entirely. Firefighters finally gained the upper hand in the wee hours of the following morning. Almost immediately after the fire had been extinguished, French President Emmanuel Macron vowed to rebuild Notre Dame.

But first, the badly damaged structure had to be shored up and stabilized and interdisciplinary teams of scientists, engineers, architects, and master craftspeople assembled to determine the best way to proceed with the restoration. That year-long process—headed up by Chief Architects Philippe Villeneuve and Remi Fromont— is the focus of a new NOVA documentary premiering tonight on PBS. Saving Notre Dame follows various experts as they study the components of the cathedral’s iconic structure to puzzle out how best to repair it.

Director Joby Lubman was among those transfixed in horror when the fire broke out, staying up much of the night as the cathedral burned, until it became clear that the structure would ultimately survive, albeit badly damaged. In the office the next morning, “Everyone was a bit shell-shocked talking about it,” he told Ars. “And it might sound opportunistic, but I thought, ‘The restoration of this icon is going to be quite something to document.'”

Lubman and his development team reached out to the appropriate authorities, and within a few weeks they were sitting in on meetings with scientists, architects, engineers, and others combining their expertise to restore Notre Dame to its former glory. “It’s the ultimate restoration and a perfect synergy between science and history,” he said.

While Lubman never felt he and his crew were in any real danger, filming on-site was a challenge because of the strict safety protocols in place. Nobody was allowed to work under the vaulting, which was cordoned off. And one scene in the documentary depicts an alarm going off on the very first day of filming because the 550 tons of badly mangled scaffolding towering over the restoration site had shifted precariously in the wind.

“We all had to leave the site,” he said, scientists included. “That set the tone for our filming, which was highly unpredictable. It was very much, we get what we get [on film] when we go on site.”

The original engineers

Notre Dame is an architectural masterpiece, a testament to the collective expertise of centuries of craftspeople. “They were the original engineers, before engineering as a term existed,” said Lubman. “You couldn’t go to school to learn engineering, it was passed down from father to son over many, many generations. It is rather lovely to think that these buildings are the product of thousands of years of experience. I think so much of that knowledge is imprinted in the materials themselves that have been used. People today can look at the craftsmanship and at the tool marks, and understand exactly how they did it.”

Among the experts featured in Saving Notre Dame is glass scientist Claudine Loisel, who was relieved to find that the cathedral’s famed stained glass windows were intact and not too badly damaged. There were microcracks in some panels from the thermal shock of the fire, and most windows were coated with the toxic lead dust that was emitted when the lead roof burned. She figured out an effective decontamination plan involving a tiny precision vacuum cleaner, followed by removal of any further residue with cotton balls soaked in distilled water. X-ray spectroscopy analysis helped her determine just how many wipes were needed to remove the lead without damaging the paint underneath.

For that segment, Lubman also took his film crew to York, where conservationists have adopted a new preservation approach to the stained glass windows of York Minster Cathedral. The cathedral caught fire in 1984, shattering the glass of the South Transept rose window, although the lead held it together, allowing it to be taken down and painstakingly reassembled. The new approach involves installing protective clear glass external frames before replacing the original stained glass windows. The gap between them improves ventilation and prevents condensation from building up on the original stained glass, as well as protecting it from damaging UV rays.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1725261