The fermented spicy cabbage known as kimchi is a staple of Korean cuisine, traditionally made in earthenware vessels known as onggi. These days most Korean households have kimchi refrigerators for that purpose, while on a commercial scale, kimchi is made via mass fermentation in glass, steel, or plastic containers. But is the kimchi made with these modern contraptions of equal quality to the traditional fermentation method? Many kimchi aficionados would argue that it is not, and now the pro-onggi faction has some science to back up that assertion.

It turns out that the porosity of the onggi’s walls help the most desired bacteria proliferate during the fermentation process, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. “We wanted to find the ‘secret sauce’ for how onggi make kimchi taste so good,” said co-author David Hu of Georgia Tech. “So we measured how the gases evolved while kimchi fermented inside the onggi—something no one had done before.”

The handmade clay vessels known as onggi have long been used by Korean chefs to ferment foods, including ganjang (soy sauce), gochujang (red pepper paste), and doenjang (soy bean paste), as well as kimchi. The cabbage or daikon is sliced into small uniform pieces, which are coated with salt as a preservative. The salt draws out the water and inhibits the growth of many undesirable microorganisms. Then the excess water is dried and seasonings are added, often including sugar, which further serves to bind any remaining free water. Finally the brined cabbage is placed into an airtight canning jar, where it remains for the next 24 to 48 hours at room temperature. The jar is “burped” occasionally to release carbon dioxide formed during the fermentation process.

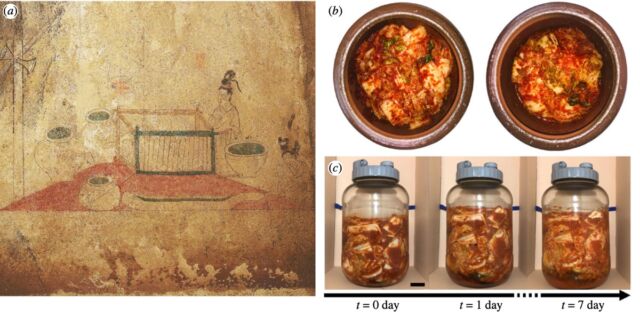

There are many varieties of kimchi, however, and the winter variety was traditionally made in large quantities to last the season, stored in the ground in large pots. Prior studies have found that kimchi fermented in onggi over a month had significantly higher growth of the desired salt-loving lactic acid bacteria than kimchi fermented in plastic or steel containers, while slowing the growth of unwanted aerobic bacteria that can impart a foul taste to the final product. Onggi have also been shown to increase the acidity and antioxidant activity of kimchi, according to Hu et al.

Hu and his team wanted to learn more about the connection between the material properties of the onggi and the growth of bacteria during kimchi fermentation, and they turned to fluid mechanics for guidance. They purchased a large onggi from a village on Jeju Island in Korea, sufficiently tall and wide to accommodate the addition of airborne carbon dioxide sensors. The onggi was made in the traditional way by hand-pressing and slapping raw mud (made up of water, silt, and clay) and picking out any pebbles. The clay was then formed into long rods and the final jar shaped on a spinning wheel before drying out. The final step involved sintering the onggi inside a kiln for a day before it was cooled down. This particular onggi was not glazed, which, the authors noted, could hamper permeability.

Hu et al. first used a scanning electron microscope and CT scanner to examine the pore structure of their onggi. Then they tested the permeability of the onggi by observing how water evaporated through the container over time. Next, they conducted experiments of the actual fermentation process by making their own kimchi—three trials each using the onggi they’d purchased and a hermetically sealed glass jar (the better to capture the process with time-lapsed video footage). Both vessels were outfitted with carbon dioxide and pressure sensors, which measured and compared the changes in carbon dioxide, since that is a key signature of fermentation.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1931767