GPS is now a mainstay of daily life, helping us with determining locations, navigation, tracking, mapping, and timing across a broad spectrum of applications. But it does have a few shortcomings, most notably not being able to pass through buildings, rocks, or water. That’s why Japanese researchers have developed an alternative wireless navigation system that relies on cosmic rays, or muons, instead of radio waves, according to a new paper published in the journal iScience. The team has conducted their first successful test, and the system could one day be used by search and rescue teams, for example, to guide robots underwater, or help autonomous vehicles navigate underground.

“Cosmic-ray muons fall equally across the Earth and always travel at the same speed regardless of what matter they traverse, penetrating even kilometers of rock,” said co-author Hiroyuki Tanaka of Muographix at the University of Tokyo in Japan. “Now, by using muons, we have developed a new kind of GPS, which we have called the muometric positioning system (muPS), which works underground, indoors and underwater.”

As previously reported, there is a long history of using muons to image archaeological structures, a process made easier because cosmic rays provide a steady supply of these particles. Muons are also used to hunt for illegally transported nuclear materials at border crossings and to monitor active volcanoes in hopes of detecting when they might erupt. In 2008, scientists at the University of Texas, Austin, repurposed old muon detectors to search for possible hidden Mayan ruins in Belize. Physicists at Los Alamos National Laboratory have been developing portable versions of muon imaging systems to unlock the construction secrets of the dome (Il Duomo) atop the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Flower in Florence, Italy, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi in the early 15th century.

In 2016, scientists using muon imaging picked up signals indicating a hidden corridor behind the famous chevron blocks on the north face of the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. The following year, the same team detected a mysterious void in another area of the pyramid, believing it could be a hidden chamber, which was subsequently mapped out using two different muon imaging methods. And just last month, scientists used muon imaging to discover a previously hidden chamber at the ruins of the ancient necropolis of Neapolis, some 10 meters (about 33 feet) below modern-day Naples, Italy.

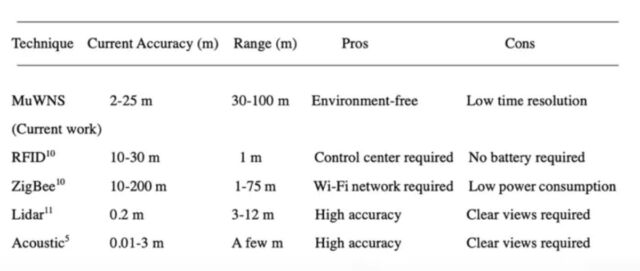

Autonomous robots and vehicles could one day be commonplace in homes, hospitals, factories, and mining operations, as well as for search and rescue missions, but there is not yet a universal means of navigation and positioning, per Tanaka et al. As noted, GPS can’t penetrate underground or underwater. RFID technologies can achieve good accuracy with small batteries, but require a control center with servers, printers, monitors, and so forth. Dead reckoning is plagued by chronic estimation errors without an external signal to provide correction. Acoustic, laser scanner, and Lidar approaches also have drawbacks. So Tanaka and his colleagues turned to muons when developing their own alternative system.

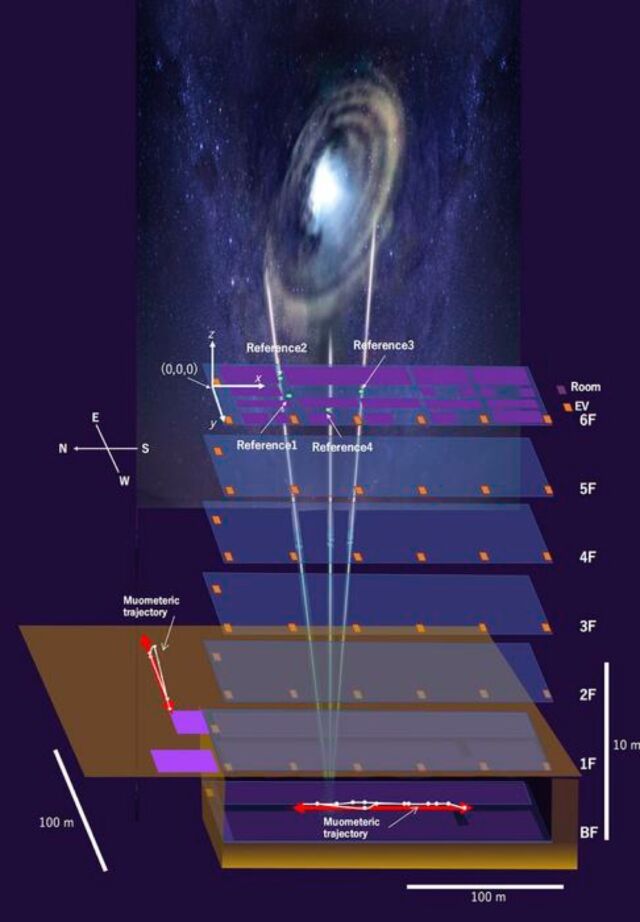

Muon imaging methods typically involve gas-filled chambers. As muons zip through the gas, they collide with the gas particles and emit a telltale flash of light (scintillation), which is recorded by the detector, allowing scientists to calculate the particle’s energy and trajectory. It’s similar to X-ray imaging or ground-penetrating radar, except with naturally occurring high-energy muons rather than X-rays or radio waves. That higher energy makes it possible to image thick, dense substance. The denser the imaged object, the more muons are blocked. The Muographix system relies on four muon-detecting reference stations above ground serving as coordinates for the muon-detecting receivers, which are deployed either underground or underwater.

The team conducted the first trial of a muon-based underwater sensor array in 2021, using it to detect the rapidly changing tidal conditions in Tokyo Bay. They placed ten muon detectors within the service tunnel of the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line roadway, which lies some 45 meters (147 feet) below sea level. They were able to image the sea above the tunnel with a spatial resolution of 10 meters (nearly 33 feet) and a time resolution of one meter (3.3 feet), sufficient to demonstrate the system’s ability to sense strong storm waves or tsunamis.

The array was put to the test in September of that same year, when Japan was hit by a typhoon approaching from the south, producing mild ocean swells and tsunamis. The extra volume of water slightly increased the scattering of muons, and that variation corresponded well to other measurements of the ocean swells. And last year, Tanaka’s team reported they had successfully imaged the vertical profile of a cyclone using muography, showing the cyclone’s cross sections and revealing variations in density. They discovered that the warm core was low-density, in contrast to the high-pressure cold exterior. In conjunction with existing satellite tracking systems, muography could improve cyclone predictions.

The team’s earlier iterations connected the receiver to the ground station with a wire, which limited movement considerably. This new version—the muometric wireless navigation system, or MuWNS—is, as the name makes clear, completely wireless, and uses high-precision quartz clocks to synchronize the ground stations with the receiver. Taken together, the reference stations and synchronized clocks make it possible to determine the coordinates of the receiver.

For the test run, the ground stations were placed on the sixth floor of a building and a “navigee” holding the receiver walked around the basement corridors. The resulting measurements were used to calculate the navigee’s route and confirm the path traveled. According to Tanaka, MuWNS performed with an accuracy of between 2 and 25 meters (6.5 to 82 feet), with a range of as much as 100 meters (about 328 feet). “This is as good as, if not better than, single-point GPS positioning aboveground in urban areas,” he said. “But it is still far from a practical level. People need one-meter accuracy, and the key to this is the time synchronization.”

One solution would be to incorporate commercially available chip-scale atomic clocks, which are twice as accurate as quartz clocks. But those atomic clocks are too pricey at the moment, although Tanaka foresees the cost decreasing in the future as the technology becomes more broadly incorporated into cellphones. The rest of the electronics used in MuWNS will be miniaturized going forward to make it a handheld device.

DOI: iScience, 2023. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107000 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1948491