SpaceX’s new-generation Starship rocket, the most powerful and largest launcher ever built, flew halfway around the world following liftoff from South Texas on Thursday, accomplishing a key demonstration of its ability to carry heavyweight payloads into low-Earth orbit.

SpaceX’s third towering Starship rocket, standing some 397 feet (121 meters) tall and wider than the fuselage of a 747 jumbo jet, lifted off at 8:25 am CDT (13:25 UTC) Thursday from SpaceX’s Starbase launch facility on the Texas Gulf Coast east of Brownsville. SpaceX delayed the liftoff time by nearly an hour and a half to wait for boats to clear out of restricted waters near the launch base.

Hitting its marks

The successful launch builds on two Starship test flights last year that achieved some, but not all, of their objectives and appears to put the privately funded rocket program on course to begin launching satellites, allowing SpaceX to ramp up the already-blistering pace of Starlink deployments.

“Starship reached orbital velocity!” wrote Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder and CEO, on his social media platform X. “Congratulations SpaceX team!!”

SpaceX scored several other milestones with Thursday’s test flight, including a test of Starship’s payload bay door, which would open and shut on future flights to release satellites into orbit. A preliminary report from SpaceX also indicated Starship transferred super-cold liquid oxygen propellant between two tanks inside the rocket, a precursor to more ambitious in-orbit refueling tests planned in the coming years. Future Starship flights into deep space, such as missions to land astronauts on the Moon for NASA, will require SpaceX to transfer hundreds of tons of cryogenic propellant between ships in orbit.

Starship left a few other boxes unchecked Thursday. While it made it closer to splashdown than before, the Super Heavy booster plummeted into the Gulf of Mexico in an uncontrolled manner. If everything went perfectly, the booster would have softly settled into the sea after reigniting its engines for a landing burn.

A restart of one of Starship’s Raptor engines in space—one of the three new test objectives on this flight—did not happen for reasons SpaceX officials did not immediately explain.

Part rocket and part spacecraft, Starship is designed to launch up to 150 metric tons (330,000 pounds) of cargo into low-Earth orbit when SpaceX sets aside enough propellant to recover the booster and the ship. Flown in expendable mode, Starship could launch almost double that amount of payload mass to orbit, according to Musk.

Starship is the vehicle Musk says is needed to make real his ambition to make human life multi-planetary. It is central to Musk’s goal of building a settlement on Mars. In the near-term, Starship will be useful for SpaceX to launch satellites. NASA also has multibillion-dollar contracts with SpaceX to develop a version of Starship to land humans on the Moon through the space agency’s Artemis program.

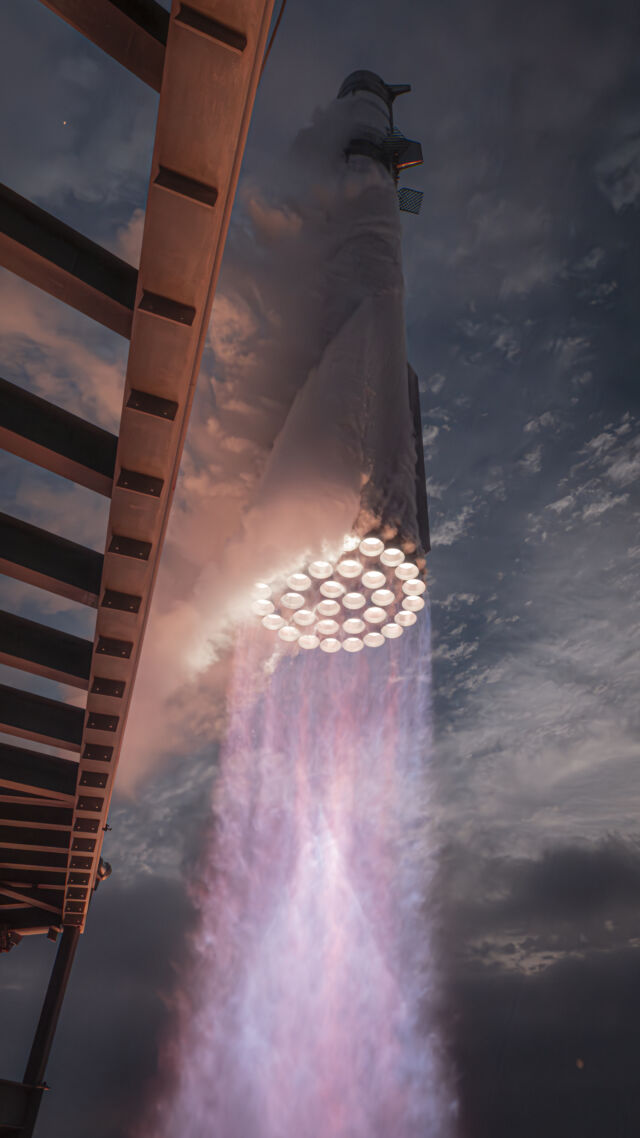

For the first time, SpaceX’s Starship hit all of its marks on the climb into space Thursday. All 33 methane-fueled Raptor engines on the rocket’s massive Super Heavy booster appeared to function as expected, generating a deep rumble heard for miles around. Burning 20 tons of propellant per second, the engines produced more than 16 million pounds of thrust to power the stainless-steel rocket on an initial vertical climb off its launch pad, then steered it east on a trajectory arcing over the Gulf of Mexico.

About 2 minutes and 42 seconds into the flight, the Super Heavy booster began shutting down most of its engines. Hot-staging occurred about two seconds later, with the nearly simultaneous ignition of six Raptor engines on the upper stage, or ship, and the separation of the Super Heavy booster.

This hot-staging technique, previously used on Russian launchers, is designed to allow the rocket to more efficiently haul payloads into orbit, without the brief interruption in thrust most rockets experience during stage separation. SpaceX first tested Starship’s hot-staging technique on the previous test flight in November.

The ship’s six Raptor engines burned for about six minutes and accelerated the vehicle to nearly 16,500 mph (about 26,500 kilometers per hour). As planned, this speed was just shy of the velocity required to enter a stable orbit around the Earth. While Starship coasted to a maximum altitude of 145 miles (234 kilometers), the low point, or perigee, of the ship’s orbit was inside the atmosphere, ensuring aerodynamic drag would bring it back to the ground before completing a full circuit of the planet.

SpaceX’s first three Starship orbital test flights have followed a steady curve of progress. The first test launch last April suffered several Raptor engine failures and damaged the launch pad in Texas; then, on its second flight in November, none of the engines failed, and the rocket nearly reached its targeted velocity before a propellant leak caused it to self-destruct over the Gulf of Mexico.

The Raptors now have a perfect record on two consecutive flights, proving the design of SpaceX’s complex new engine, similar in performance to the space shuttle’s main engine, is maturing after earlier concerns about its reliability.

Cameras aboard the Super Heavy booster and Starship captured dazzling video of each event on Thursday’s test flight. One camera view showed the rocket’s fiery hot-staging from a perspective unseen on the last Starship test flight. In space, Starship could be seen slowly spinning as it cruised halfway around the planet, first over the Gulf of Mexico, then the Atlantic Ocean, and Africa.

One camera shot inside the ship showed light reflected off the spacecraft’s stainless-steel structure, apparently from sunlight shining through the open payload bay door.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=2010195