Update, 4:45 pm ET: Well, they did it.

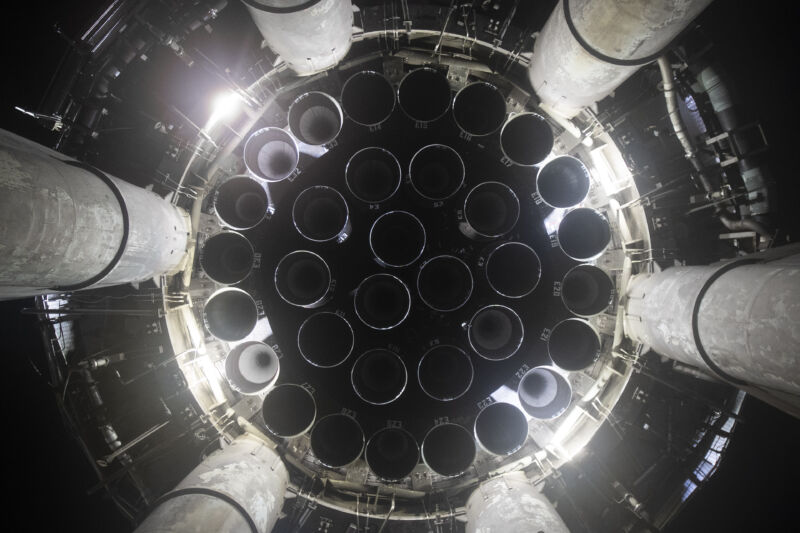

At around 3:15 pm local time in South Texas, SpaceX ignited its Super Heavy rocket for a “full duration” test of its Raptor engines. According to SpaceX founder Elon Musk, the launch team turned off one engine just prior to ignition, and another stopped itself. Still, he said 31 of 33 engines would have provided enough thrust to reach orbit. This is a huge milestone for SpaceX that potentially puts the company on track for an orbital test flight during the second half of March or possibly early April.

This is the most engines ignited on a rocket ever. The thrust output of these engines, too, was likely nearly double that of NASA’s Saturn 5 rocket or Space Launch System. The good news for SpaceX is that, at least from early views, the launch infrastructure in South Texas looked mostly unscathed.

Bringing the HEAT 🔥

–@NASASpaceflight pic.twitter.com/TLeJASNLlV

— Nic Ansuini (@NicAnsuini) February 9, 2023

Original post: After years of preparatory work, SpaceX plans to ignite all 33 of the main engines on its massive Super Heavy rocket booster today. This is the first stage of the company’s Starship rocket, which is intended to be fully reusable, to help power NASA’s return to the Moon and one day possibly help humans settle on Mars.

No rocket has ever used so many engines before. The closest comparison is the Soviet Union’s N1 rocket, which had a first stage powered by 30 NK-15 liquid-fueled engines. However, each of these engines was only about two-thirds as powerful as the Raptor 2 rocket engines bolted to the Super Heavy rocket.

And, oh yeah, the N1 was a massive failure. Intended to compete with NASA’s Saturn V rocket and form the backbone of a Soviet Moon program, the N1 rocket attempted four launches from 1969 to 1972. All were busts, including one—the second launch, just two weeks before the Apollo 11 Moon landing in July 1969—that destroyed its launch complex as the rocket failed shortly after liftoff.

Such is the history before SpaceX today as it tests the Super Heavy booster by igniting all its Raptor engines for a few seconds, with the rocket held firmly to the ground.

Speaking Wednesday at a commercial space conference in Washington, DC, SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell said Thursday would be a “big day” for the company. “Keep in mind, this first one is really a test flight,” said Shotwell, who knows her spaceflight history. “The real goal is to not blow up the launch pad, that is success.”

In truth, after a rapid-fire test campaign in 2020 and 2021 of Starship prototypes, the company has moved more cautiously at its development and test facility in South Texas, known as Starbase. This is because the company has likely invested more than $1 billion in a massive launch-and-catch tower to support Starship and Super Heavy, as well as ground systems to support fueling of the massive vehicles.

Because so many assets are clustered in a small area near the Gulf of Mexico, SpaceX really does not want to take the risk of destroying infrastructure it has spent more than a year building and testing. This would set the Starship launch campaign back months, at least, as the area is rebuilt. It would also probably redouble regulatory concerns that were raised as part of the Federal Aviation Administration’s process to clear the South Texas location for experimental orbital launches.

So Shotwell is correct when she says the main goal today is to not blow up the launch pad. After that, SpaceX will work to glean data about the performance of the Raptor engines on the rocket and replace those that show deviations from expected behavior.

If this test goes reasonably well, it would put SpaceX on a path toward its first orbital launch attempt, now likely to occur no earlier than the second half of March or perhaps in April.

There is no set time for today’s test. The road closure for the Boca Chica area runs from 8 am CT (14:00 UTC) to 8 pm CT (02:00 UTC Friday) local time. It is also not known whether SpaceX will broadcast the test. However, there are several streamers (such as NASASpaceflight and LabPadre) expected to provide uninterrupted coverage of whatever happens on the launch pad.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1916372