Compared to fossil fuel plants, renewable power facilities cover a lot of ground. That ground can be put to additional uses; many wind farms are also regular farms, and even solar plants can work well with agriculture. But these sorts of developments are definitely not compatible with conserving sensitive habitats for wildlife or plants. Even wind farms, which have a relatively small on-ground footprint, require access roads and regular servicing.

Early studies on the matter suggest this might be a serious problem, as they found that a number of renewable power facilities had been built on land that had been identified as a sensitive habitat. But new work from researchers at the University of Southampton indicates that the problem isn’t as severe as it seems. The actual footprint of existing wind and solar farms on sensitive habitats is small and should be able to be kept small in most countries.

Carbon-free footprints

To understand present problems, you must have an idea of what land has been developed and what needs to be conserved. The researchers used two different sources to identify the footprints of current renewable power facilities. For sensitive habitats, the team started with a database of all existing protected areas. It supplemented that with maps of the ranges of all land vertebrates listed as threatened on the “Red List” as well as the World Wildlife Fund’s list of ecoregions. The protected areas were considered a starting point, and areas for potential expansion were identified based on their ability to protect the most threatened species.

Sufficient data wasn’t available for every region, notably all of Africa and Australia and countries like Indonesia and Mexico.

Based purely on overlap, the numbers are consistent with the earlier analyses: about 15 percent of the existing facilities occur within conservation areas. Most of this overlap occurs in Europe, where undeveloped habitat is often rare and renewables have been pursued aggressively.

Separately, however, the researchers looked at the total footprints of both the renewable sites and key habitats within each country. This allowed them to estimate how much overlap between the two (sites and habitats) we’d expect to see if both were distributed randomly. This helps address the question of whether sensitive habitats are especially vulnerable to being developed for renewable power.

In Europe, only Spain, Portugal, and France saw any indication of elevated overlap between renewables and sensitive habitats. Outside of that, the United States saw high levels of overlap, but these mostly occurred in the Great Plains, where other areas provided significant habitat protections. More concerning is Brazil, where high species densities make it difficult to find places where development isn’t problematic.

To get a sense of whether problems were arising from existing developments, the researchers checked for areas that had been de-listed as reserves or identified as having degraded habitats. There was no indication that these changes were driven by renewable energy development.

Ready to expand

Obviously, existing renewable energy facilities don’t come anywhere close to allowing us to hit our climate goals, so we’re going to have to expand them dramatically. Efforts are also underway to dramatically expand the protected habitats in many areas of the globe. How likely are those expansions to collide in the future?

To find out, the researchers looked into locations where renewable resources are being developed currently and projected those developments into the future. The researchers found that wind farms tend to be developed in areas with the best wind resources. By contrast, other considerations (such as proximity to road infrastructure) were the biggest factor for the siting of solar power installations. Expansion of protected habitats was modeled based on maximizing the number of protected species within them.

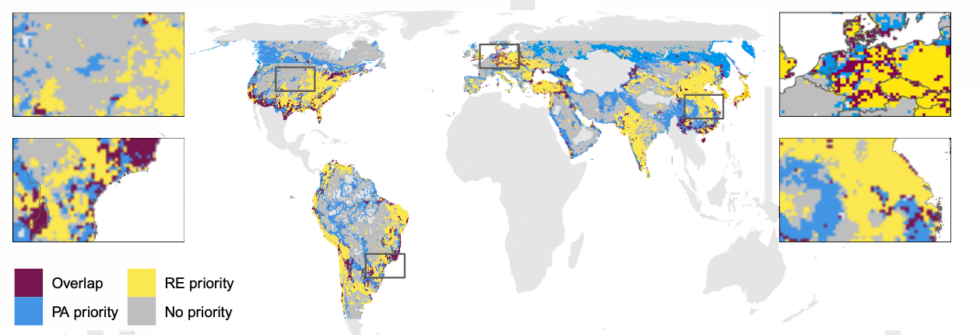

Based on these criteria, the researchers identified the top 30 percent of the regions that were likely to see renewable power development, as well as the top 30 percent that were likely to see habitat protection. These were compared to identify conflicts.

Overall, the news is pretty good; there are large regions around the globe where conflict is unlikely. In many other areas, like Southern India and the US Great Plains, potential conflicts can be easily avoided because only a small portion of the area suited for renewable power development ends up overlapping with areas that should be prioritized for habitat preservation.

That said, a number of areas sit where conflicts are almost inevitable. Large areas of Southern Brazil and Southeast Asia are likely to see conflicts, as is the area bordering the Red Sea. Solar power in Central Europe is already on the verge of running into limits on development.

Of course, all this assumes that the trends for future renewable power siting will be an extension of the present trend, which is not guaranteed. And there are some highly specific conflicts that may be difficult to resolve, such as the risk posed to birds and bats from smaller on-shore wind turbines. On the more positive side, greater international integration of power grids may allow some smaller countries to benefit from renewable power without developing their own protected areas.

PNAS, 2022. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2104764119 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1830907