There’s a popular myth that divides people into “left brain” and “right brain” categories, whereby the former are analytical and logical, while the latter are creative and innovative. The reality, of course, is much more complicated than that, and a new brain-imaging study of improvisational jazz guitarists is a useful case in point. Researchers at Drexel University found that while the right hemisphere is associated with creativity in fairly inexperienced jazz musicians, experts with high mastery of improvisational skills actually rely primarily on the left hemisphere of the brain. They described their results in a recent paper in the journal NeuroImage.

Co-author David Rosen is a musician and scientist who started playing the piano at age eight before picking up the bass guitar in high school. (Rosen’s band, Nakama, has just released a new EP, for those looking to explore some new musical vibes while we’re all under isolation orders.) Because improvisation—defined as “the spontaneous invention of melodic solo lines or accompaniment parts”—is a defining feature of jazz, Rosen thought it would provide an excellent opportunity to explore the brain’s role not just in creativity, but more broadly in musical perception and expression.

“I think there are a lot of interesting questions to ask about [musical] perception, both for people who are listening to music and people who are performing music,” Rosen told Ars. “The brain is the part that makes us most human and lets us feel those emotions. It’s almost not possible to quantify the altered state we get into when we’re performing or listening to the music we like the most and that means the most to us as individuals. Ultimately, we’re trying to ask very focused scientific questions about pieces of what it means to share in that musical experience.”

In the zone

Jazz musicians often talk about moments during live performances when all the band members are “in the zone,” so to speak, reacting and responding to each other, instead of being more internally focused on their own independent creative choices. That, for Rosen, is the essence of improvisation.

“Mastery in jazz is very much dependent on one’s ability to improvise in all different kinds of scenarios with different musicians all the time,” said Rosen. “And improvising in jazz is really difficult because of how many different chords there are. The chord sequences can be pretty complex, with changes happening really fast.” From a neuroscience perspective, that’s the sort of task that places a heavy cognitive load on the brain, yet master jazz musicians can perform this demanding task in real time thanks to years and years of rigorous training.

Exactly how does one go about measuring a nebulous concept like “creativity” with any degree of robustness? Rosen et al. used a well-established method known as the “consensual assessment technique” for their study, in which experts review material—whether it is music, film, and so forth—on different kinds of scales. In this case, a panel of four expert musicians and teachers assessed how creative the subjects’ improvisations were, the aesthetic appeal of the performances, and the subjects’ technical proficiency.

All three measurements were collected independently and proved to be highly correlated, giving the team a measurable quality score for the experiment. As for the expert panelists, their “inter-rater reliability” across all three scales was very high. “So we have some indication that these people are consistent in their measures,” said Rosen. “Without that reliability, we would just be saying, ‘OK, score random people’s opinions.'”

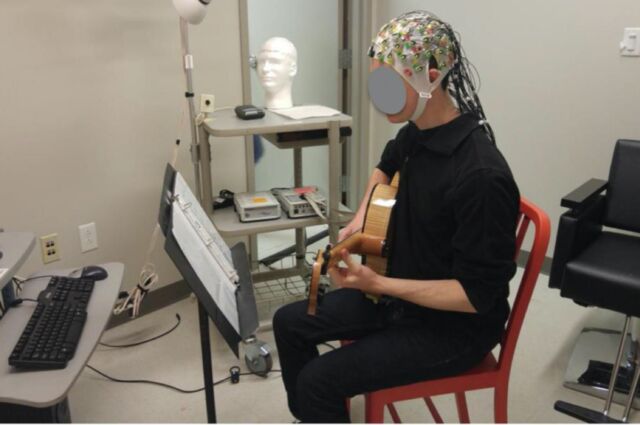

Thirty-two jazz guitarists—some highly experienced, some relative novices—participated in the study. Each subject was asked to improvise to six jazz lead sheets while hooked up to an EEG machine. Their playing was accompanied by programmed drums, bass, and piano. The resulting 192 recordings were then played back to the expert panel, who evaluated them for creativity and other associated qualities. Then Rosen et al. compared the highest and lowest rated recordings with the recorded EEGs to see which areas of the brain showed more activity.

The initial results showed that there was more left-brain activity for highly rated performances on the creativity scale, with greater right-hemisphere activity for those performances with lower ratings. According to Rosen, that finding makes sense once one factors in a musician’s degree of experience.

While the right brain is associated with things like conscious control and motor planning, the left side of the brain is generally more engaged during habitual or routine tasks. “If you do something over and over and over again, you’re going to become really good at that task,” said Rosen. “But that might not necessarily tell us when the expert is having a novel or creative experience while they’re doing the task. In our behavioral models, we saw that expertise was contributing quite a bit of variance in predicting the scores of the improvisation ratings.”

-

SPM topographic significance maps from the jazz improv study.D.S. Rosen et al./Drexel University

-

Brain activity maps showing areas associated with high-creativity performances compared with lower-creativity performances. Each map shows a top view of the head.Drexel University

If expertise was the primary driver behind the observed effect, then when the team statistically controlled for level of expertise (particularly when it came to public performance), they should have found little difference in the brain scan data. Instead, there were significant differences in the right-hemisphere brain activity (especially the frontal region) between performances rated highly creative and those that received lower creativity ratings.

In short, experts were rated the highest by the panel even though they were approaching the task of jazz improvisation with the most habitual routines. Rosen attributes this in part to the fact that a novice must go through 16 bars of music on a lead sheet quarter by quarter, for instance, whereas an expert will be able to find patterns, like a two-five-one progression. “That allows them to approach the test with a reduced level of that cognitive control,” he said. So creativity is associated with the right hemisphere when we’re dealing with an unfamiliar situation and associated with the left hemisphere when we are highly experienced with the task at hand.

“If creativity is defined in terms of the quality of a product, such as a song, invention, poem, or painting, then the left hemisphere plays a key role,” said Rosen’s co-author, John Kounios, director of Drexel’s applied and cognitive brain sciences program. “However, if creativity is understood as a person’s ability to deal with novel, unfamiliar situations, as is the case for novice improvisers, then the right hemisphere plays the leading role.”

A dual process

This experiment will feed into a growing body of research at Rosen’s new music technology startup venture, Secret Chord Laboratories, which develops software to predict the response listeners will have to a given piece of music. The company is currently targeting the recording industry, which is always looking for the next hit single. (Rosen describes its mission as “an interdisciplinary exploration of the neuroscience of music.”)

The core technology grew out of an earlier study Rosen did with Georgetown University’s Scott Miles on music perception examining what, if any, patterns of sound produce a pleasure response in the brain. They looked at Hot 100 songs on the Billboard charts, from “Johnny B. Goode” in 1958 through Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” in 1991. “We analyzed every single chord of every one of those songs, and we did a statistical test to see if those charting in the top quartile had a different level of what we call ‘familiar surprise,’ in terms of the harmonic structure,” said Rosen.

They found that the most popular songs had a high level of harmonic surprise, defined as points where the music deviates from listener expectations—the use of relatively rare chords in verses, for example, instead of just sticking with, say, the standard C-major chord progression (C, G, F). The best songs follow up that harmonic surprise with a catchy common chorus. The resulting patents—since expanded to include rhythm, melody, timbre, and lyrics, as well as harmonies—led to the formation of the company.

Rosen and his colleagues next plan to analyze the jazz guitarist data to examine the neural correlates of so-called “flow states.” He also thinks it might be possible to design an experiment to test his hypothesis that jazz musicians engage in a form of “switching,” amassing various tricks and techniques they can use if they become momentarily at a loss during an improvisational performance. “Once we can have people back in the labs again, we could throw in really weird chords, or have music that doesn’t match the lead sheet, to see how quickly they respond to being thrown off,” he said.

“My hypothesis is that [experts] would be able to revert back to the brain state they were in before more quickly than a novice would be able to,” said Rosen. “The dual process is not just that novices use all control and executive functioning and that experts use none. It’s about the interaction of those systems, and which ones are predominant in the different levels of expertise.”

DOI: NeuroImage, 2020. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116632 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1666696