For the last several years, the Pew Research Center has been tracking the US public’s views on scientists and science-related issues. This year’s survey finds a continuation of a worrisome trend: the US public has a rising trust in scientists, but it’s mostly due to an increased respect among Democrats.

The timing of the survey was such that Pew was able to add a number of questions about the COVID-19 pandemic and the policy response to it. The parties also showed differences in their view of policy responses, as you’d expect. But they also differ in how they view basic, easily confirmable facts.

Some good news, some bad news

Pew has been surveying a group of over 10,000 US residents, balanced to reflect the country’s demographics, for four years now. The number is high enough to provide a very good representation of public opinion, and the length of time is now sufficient to see consistent trends rise above annual fluctuations. This makes it a fantastic resource for tracking the public’s changing views of science and its role in society.

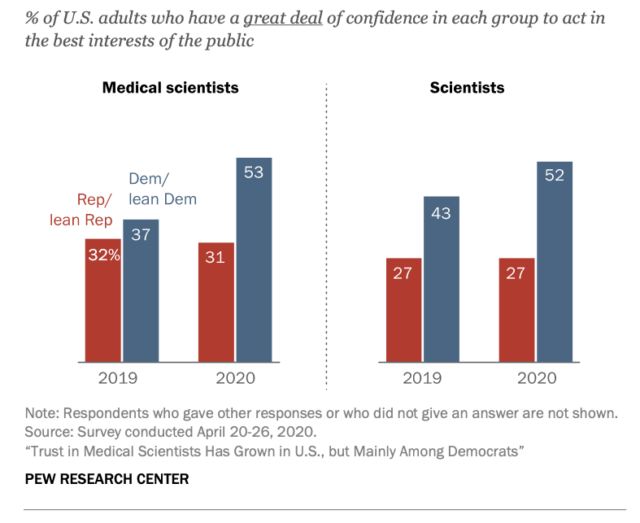

Some of that change is clearly positive. When asked about whether they had confidence that scientists would act in the public’s interest, 39 percent had a great deal, and another 48 a fair amount. That’s up from 21 percent/55 percent just four years ago. When asked the same question about medical researchers, 43 percent had a great deal of confidence, and another 46 percent a fair amount, up from 24/60 in 2016. The growth over that time has been steady, indicating that this wasn’t a one-off surge due to the pandemic.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the shift was powered entirely by people who identify as Democrats or lean in that direction. Republicans are not part of the growing support for the research community.

Accompanying those positive views is a shift on the role of science and scientists in policy issues related to the field. Just a year ago, slightly over half the public felt that public opinion should play an important role in guiding science-related policy decisions. This year, 55 percent of the survey group felt that public opinion shouldn’t have an important role, largely choosing the answer “because these issues are too complex.” Accordingly, 60 percent of the participants felt that scientists should play an active role in shaping these policy decisions.

But again, this view was much more common among Democrats. Seventy-five percent of them advocated scientists take part in policy decisions, and 60 percent felt scientific experts are better at making these decisions. By contrast, only a third of Republicans felt that scientists are better.

Pandemics and facts

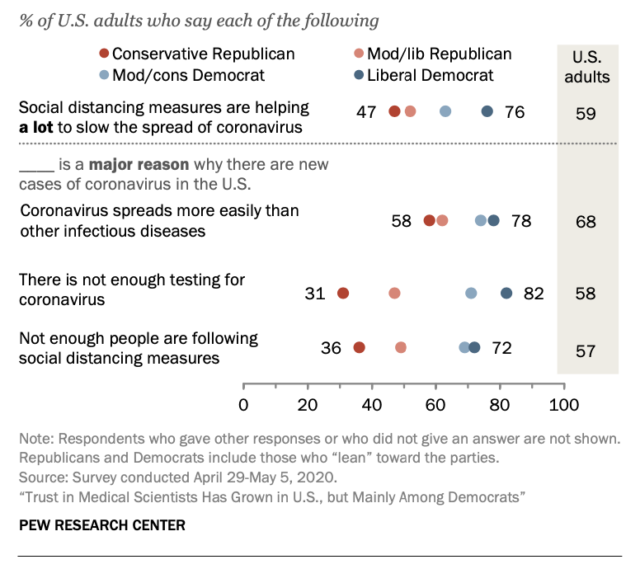

Obviously, the ongoing pandemic has made science-focused policy decisions a major concern. But here, as elsewhere, people are filtering their decision-making through the lens of partisanship. There’s now strong evidence that social distancing policies cut the rate of new infections. But fewer than half of Republicans think that’s the case; by contrast, nearly 70 percent of Democrats do. On testing, the gap is similar but even larger. Seventy-five percent of Democrats feel our testing capacity is too low, a conclusion shared by many experts. Only a bit over a third of Republicans do.

More generally, Republicans are hesitant to assign any reasons for the continued spread of the pandemic in the US. By contrast, most Democrats cite the virus itself, our lack of testing, and the lack of effective social distancing.

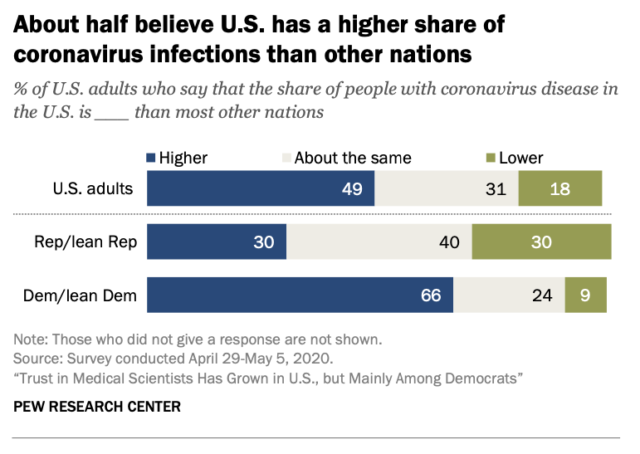

But the most striking feature of the partisan divide is that it extends to basic facts. It has been widely reported that the US has the most cases of any country so far. Even adjusting to a per-capita measurement places the US above any country other than Spain, which it’s poised to eclipse. Among Democrats, two-thirds accept that the number of cases in the US is higher than in most other countries, with acceptance rising among those with higher levels of education. Among Republicans, however, only 30 percent do, and there’s no change as education levels rise.

About the only place there’s general agreement among the two parties is that state governments have had more science-focused policy responses than the federal government.

So overall, the big picture is good: the public continues to trust that scientific experts have the public’s best interests in mind and is generally supportive of an increased role of science in policy-making. These trends existed before the pandemic, and the crisis has done little to change them. But underneath that picture is a disturbing trend, with only one party growing increasingly comfortable with scientific input on policy issues and an increasing gap in the willingness to accept information generated through scientific analysis.

But there is some good news, in that younger Republicans are much more moderate in their views toward scientists, falling somewhere between their elders and Democrats.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1677877