On a night that seemed like any other, a perfectly healthy 38-year-old man in Massachusetts fell from his bed amid a violent seizure at 4 am. The commotion woke his wife, who found her husband on the floor, shaking and “speaking gibberish.” He was rushed to Massachusetts General Hospital.

There, doctors witnessed the man have a two-minute-long tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure, in which he lost consciousness and his muscles aggressively contracted. Doctors began the painstaking process of trying to piece together what was wrong by performing a battery of tests and interviewing his family.

By nearly every account, the man was in very good health. He had no history of seizures or of any cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or neurologic disorders. His toxicology screens were clear. He took no medications, prescribed or over-the-counter. He didn’t smoke and rarely drank. There was no evidence that anything had happened to him recently that would provoke a seizure; the man had spent the previous day with his children, then he had dinner with his brother, who reported nothing out of the ordinary. The only initial hint of the diagnosis to come was that the man had immigrated to Boston from a rural area of Guatemala about 20 years earlier.

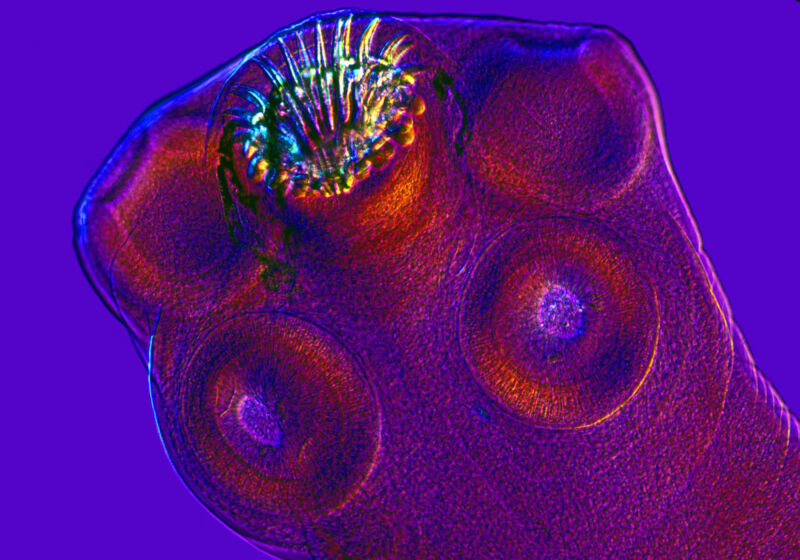

But when doctors performed a CT (computed tomography) scan of his head, they quickly narrowed the possibilities. The scan revealed three calcified lesions in his brain, and doctors homed in on the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. In other words, larval cysts from a pork tapeworm had migrated to his head years ago and nestled into various parts of his brain. The doctors documented their work on the man’s illness in a case study published on Thursday, November 11, in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Gut to brain

Learning about the path to neurocysticercosis is not for the weak of stomach; it’s a cruddy calamity as nauseating as it is dangerous. The pork tapeworms, Taenia solium, typically tuck into human intestines, where they can grow to a shocking length of two to eight meters. The worm’s victims, meanwhile, expel parasitic eggs in their feces. If that egg-laden excrement makes its way into an environment with pigs, the pigs can carry out the worm’s life cycle by ingesting the eggs.

In the pig’s stomach, gastric acid prompts the eggs to lose their protective coating and hatch into larval cysts, called oncospheres. These can penetrate the intestinal wall and take a ride through the pig’s body via the circulatory system. They eventually burrow into the pig’s muscles and lie in wait as cysticerci—which are typically not a bother for the pig.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1812394