Engineer Ken Keiter recently came into possession of one SpaceX Starlink user terminal, the satellite dish that SpaceX nicknamed “Dishy McFlatface.” But instead of plugging it in and getting Internet access from SpaceX’s low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, Keiter decided to take Dishy apart to see what’s inside.

The teardown process destroyed portions of the device. “I would love to actually test out the [Starlink] service and clearly I didn’t get a chance to, as this went a little bit further than I was intending,” Keiter said toward the end of the 55-minute teardown video he posted on YouTube last week.

Keiter, who lives in Portland, Oregon, was impressed by the Starlink team’s work. “It’s rare to see something of this complexity in a consumer product,” he said in reference to the device’s printed circuit board (PCB), which he measured at 19.75″ by 21.5″.

Let’s take a look at what Keiter found inside Dishy.

The first layer

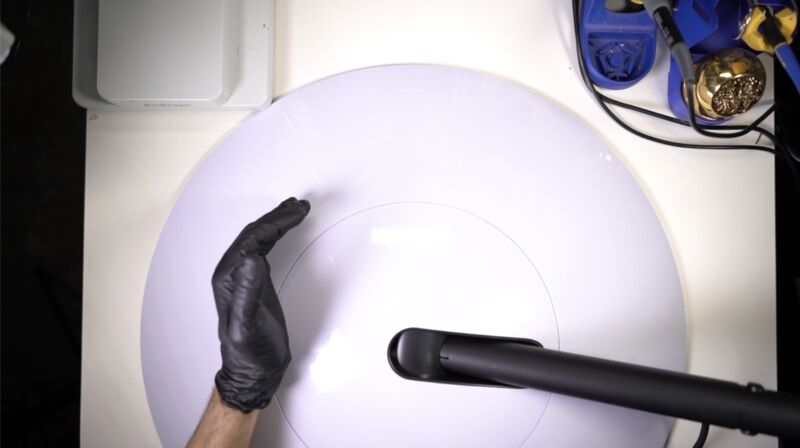

With the satellite dish face down, Keiter pulled off the back panel and found the motor assembly that Dishy uses to reposition itself to get a direct view of SpaceX satellites:

-

Pulling off the bottom part reveals two rotating motors that allow the satellite dish to reposition itself.

-

Keiter holds an Ethernet cable that was connected inside the satellite dish.

-

The motor assembly after being removed completely from Dishy.

-

Keiter rotates the motors by hand.

Keiter was intrigued by the Ethernet cable. “A lot of people have been asking why you can’t replace the cable on your own, ‘why can’t I just have a jack that I plug my own cable into in the back of Dishy?’ Well, there’s a really interesting reason for this and it has to do with power delivery,” Keiter said.

Power over Ethernet is usually limited to about 30 watts, but new standards allow for greater power delivery that can meet Dishy’s need for about 100 watts, Keiter said. Dishy uses a thick, “well-shielded” Ethernet cable that can deliver data and the required power without over-heating, he said.

Dishy suffers harm

Inside the satellite dish, Keiter found Dishy’s PCB and phased-array antenna assembly, all in one large disc protected by a metal shield. “This is the entire brains of Dishy and look how thin it is. it’s insane,” he said. He also noted that “there are really good RF reasons for having a massive shield over the whole back of it.” The metal shield was attached to the PCB by lots of glue, and Keiter had to damage the shield in order to detach it:

-

From inside the satellite dish, a metal shield covers the antenna and printed circuit board (PCB), the “brains” of Dishy.

-

Keiter was impressed by the thinness of the large disc.

-

Keiter uses a knife to cut through the glue holding the metal shield to the PCB and antenna array.

-

Removing the metal shield was difficult, and it was damaged in the process.

-

On the shield’s opposite side, blue dots made of a thermally conductive material are used to conduct heat from the PCB into the metal shield.

-

Close-up of the blue dots.

PCB and antenna array

After removing the shield, Keiter examined the PCB and antenna array:

-

Dishy’s PCB after being detached from the metal shield.

-

Close-up view of RF components.

-

Close-up of the user terminal’s application processor.

-

Close-up of the GPS receiver.

-

Close-up of connectors that are normally exposed through an opening in the metal shield.

-

The phased antenna array, which was slightly damaged in the teardown.

-

Close-up of the antenna components.

As Hackaday wrote in an article on Keiter’s teardown, it “appears that the antenna is a self-contained computer of sorts, complete with ARM processor and RAM to run the software that aims the phased array. Speaking of which, it should come as no surprise to find that not only are the ICs that drive the dizzying array of antenna elements the most numerous components on the PCB, but that they appear to be some kind of custom silicon designed specifically for SpaceX.”

Generally speaking, Dishy obviously is not user-repairable. But Keiter said he can imagine some people putting the PCB and antenna array into a different enclosure. “You could design, realistically, your own base for Dishy pretty easily and I’m guessing that is in fact what some people may choose to do,” he said.

With a Starlink beta having recently begun, SpaceX is seeking US permission to deploy up to 5 million user terminals and is already authorized to deploy 1 million. SpaceX is charging $499 for the user terminal and $99 a month for broadband service.

For the full teardown experience, including Keiter’s analysis, you can watch his video here or on YouTube:

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1726788