Most of what we know about ancient Egyptian mummification techniques comes from a few ancient texts. In addition to a text called The Ritual of Embalming, Greek historian Herodotus, in his Histories, mentions the use of natron to dehydrate the body. But there are very few details about the specific spices, oils, resins, and other ingredients used. Fortunately, science is helping fill in the gaps. A team of researchers used molecular analysis to identify several basic ingredients used in mummification, according to a new paper published in the journal Nature.

Egyptian embalming is thought to have started in the Predynastic Period or even earlier, when people noticed that the arid heat of the sand tended to dry and preserve bodies buried in the desert. Eventually, the idea of preserving the body after death worked its way into Egyptian religious beliefs. When people began to bury the dead in rock tombs, away from the desiccating sand, they used chemicals like natron salt and plant-based resins for embalming.

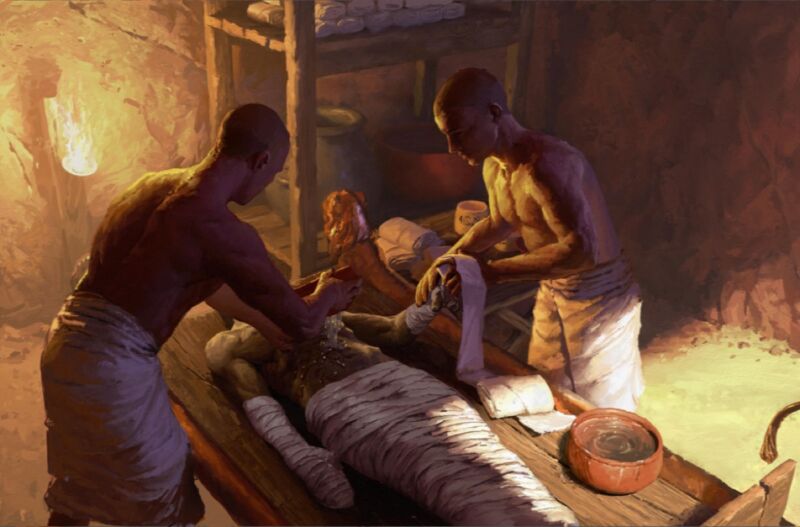

The procedure typically began by laying the corpse on a table and removing the internal organs—except for the heart. Per Herodotus, “They first draw out part of the brain through the nostrils with an iron hook, and inject certain drugs into the rest” to liquefy the remaining brain matter.

Next, they washed out the body cavity with spices and palm wine, sewed the body back up, and left aromatic plants and spices inside, including bags of natron. The body was then allowed to dehydrate over 40 days. The dried organs were sealed in canopic jars (or sometimes put back into the body cavity). Then the body was wrapped in several layers of linen cloth, with amulets placed within those layers to protect the deceased from evil. The fully wrapped mummy was coated in resin to keep moisture out and placed in a coffin (also sealed with resin).

Back in 1994, a pair of archaeologists memorably tried to replicate the mummification process, which is how they discovered that it was easier to remove the brain from the cranium if the organ was allowed to liquefy and drain naturally with the help of gravity rather than using a hook to yank the brain matter out. This was confirmed in 2008, when CT scans revealed the remains of a rod-shaped tool inside a mummy’s cranial cavity, sans hook, contradicting the account of Herodotus.

This new work builds on a 2018 study in which University of Tübingen Egyptologist Stephen Buckley and his colleagues analyzed organic residues from the mummy’s wrappings with a technique called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The method sorts vaporized chemical compounds by their mass so scientists can analyze the chemical composition of a sample. As we reported at the time, they found that the wrappings were saturated with a mixture of plant oil, an aromatic plant extract, a gum or sugar, and heated conifer resin. Those ingredients were essentially the same ones used to treat the bodies of New Kingdom royalty 2,500 years later. These compounds helped ensure that decay-causing bacteria couldn’t recolonize the body once it had been dried out.

The findings supported an earlier 2001 study by Buckley (then at the University of Bristol) and his colleague, Richard Evershed, in which they found evidence of very similar embalming compounds on fragments of linen wrappings that had come from a Predynastic burial in Mostagedda, about 374 km (232 miles) north of the Turin mummy’s long-lost grave. Some of those wrappings dated to as early as 4300 BCE (about 600 years older than the Turin mummy), and others dated to as late as 3100 BCE, but none were still associated with an actual mummy. The 2018 study was the first to identify Predynastic embalming materials in an intact mummy.

Now Buckley is back with a new team of colleagues, this time analyzing the residues on a collection of 31 ceramic vessels excavated from the Saqqara necropolis near Cairo—specifically from an embalming workshop dated between 664-524 BCE (the 26th Dynasty). Saqqara served the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis and boasts numerous pyramids, including the Step pyramid of Djoser, whose design and construction is usually attributed to Imhotep, chancellor to the Pharaoh Djoser. Over the years, archaeologists have unearthed many tombs, artifacts, and mummies while excavating the site: a rare gilded burial mask, for instance, several dozen caches of mummies, and, most recently, a new papyrus of the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1913572