Archaeologists found the bones of three young African men in a 500-year-old mass grave in what is now Mexico City. The chemical makeup of their bones sheds light on their earlier lives in Africa, and forensic analysis reveals hard, painful lives and young deaths.

How the dead speak

Archaeologists unearthed the mass grave in 1992 while digging a new subway line in Mexico City. Five hundred years earlier, the site had been the grounds of the Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales. The Spanish colonizers had built the hospital to treat indigenous people—that’s what “los Naturales” means in Spanish—but these three men were African, not North or Central American. Their bones radiocarbon-dated to the 1500s CE, which makes them part of an important but often anonymous group of people: the first African people abducted in their homelands and brought across the Atlantic Ocean to European colonies in the Americas.

Of the 10 to 20 million people transported to the Atlantic over the next 300 years, nearly 150,000 of them ended up, like these three men, in the colony of New Spain. Like countless other oppressed and otherwise overlooked people throughout human history, they left behind no written accounts, no artifacts to hint at their lives, and no names. Only their bones tell their stories.

And the stories they tell are difficult to witness, even now. All three men died young, in their mid-20s; their skeletons bore the marks of years of brutally hard labor, bone-breaking injuries, and a starvation diet. In their teeth, archaeologists found traces of DNA from two pathogens that probably left the men with painful chronic illnesses. But their bones also tell the story of where they came from, written in chemical isotope ratios and DNA.

Hard, painful lives

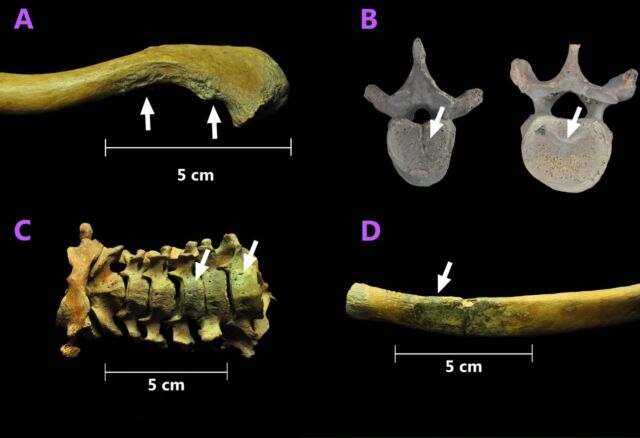

All three men were around 25 years old when they died, but brutal physical strain had worn their bodies down. One man, by his mid-20s, already had five herniated discs in his back, and his left collarbone had been reshaped by years of carrying heavy loads on his shoulders—probably the same loads that had wrecked his back. Another had osteoarthritis in at least one knee and a lower spine full of degenerative bone damage usually only found in much older people. The third man bore the same evidence of backbreaking toil.

Sometime before his death, the man with the bad knee had taken a cut to the forehead, a blow that cut into the bone and had only begun to heal when he died. His leg had also been broken and never set properly, leaving the bones to heal at an angle. The man with the collection of herniated discs had traces of green discoloration on two ribs and the vertebrae of his neck.

“It is likely that this individual had been shot and buried with the fragments in his body, thus resulting in the green coloration,” wrote archaeologist Rodrigo Barquera, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and his colleagues.

And all three showed signs of poor health: spongy, porous bone in the vaults of their skulls and the tops of their eye sockets, called cribra orbitalia. Bone forms like this when a person is badly malnourished; usually it’s caused by iron-deficiency anemia from poor nutrition, intestinal parasites, or a chronic infection.

Young and far from home

But it’s likely that their lives weren’t always so full of misery and pain. None of these three men was born into slavery in New Spain; they came from sub-Saharan Africa.

When plants grow, they take up nutrients from the soil and rock, including an element called strontium. The body uses strontium to help build bone, so the ratio of different strontium isotopes in your bones and teeth carries the signature of the places you’ve lived. The strontium in all three men’s teeth suggests that they grew up far away from Mexico, probably in West Africa.

The world they left behind

When they were captured and hauled to New Spain, the men brought elements of their own cultures with them. One of the first things that tipped off Barquera and his colleagues that these men might have come from Africa was their teeth, which had been filed and decorated. Many groups of people around the world have sharpened, shaped, or removed their teeth. Sometimes it’s part of a ritual with spiritual significance, but often it’s just about their culture’s view of looking good—not so different from tattoos, body piercings, or any of the other ways we try to customize how we look.

The man with the bad knee and the third man both had their upper incisors filed into a T-shape, which looks a lot like the way people of the modern D’zem group, who now live in Cameroon, file their incisors. Meanwhile, the same man who had so many herniated discs had, at some point in his life, filed his upper incisors into a V-shape. Today, several groups of people living in Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and northern Gabon file their incisors into a similar shape, and several other groups did so in the past.

But many groups in Africa have moved and in a few cases died out entirely over the last few centuries (thanks largely to European colonization and slavery). And several groups, today and in the past, have filed their teeth in similar ways. That makes it impossible to definitely link these three men to a modern group of people, or the place they came from, based on how they styled their teeth.

So Barquera and his colleagues compared the three men’s DNA with a database of genomes from modern people. The man with the herniated discs was more closely related to the modern Mende people of West Africa than to any other group of people alive today. The other two were more closely related to the Wambo people of Southern Africa than to anyone else.

But all three men shared some of their ancestry with several groups of people in sub-Saharan Africa, including some who now live in Central Africa. Barquera and his colleagues say centuries of slavery, colonization, and displacement have changed the demographic landscape of Africa. DNA from the three men in Mexico City may help tell not just their stories but the story of how colonization and slavery changed a continent.

The microbes they carried

In the same way, two of the three men are helping tell the story of how diseases, not just people, moved between continents. Barquera and his colleagues found DNA from the hepatitis B virus in one man’s tooth (the man with the herniated discs), and it’s a strain of the virus that’s only found in Africa and Haiti today. It’s the first trace of this hepatitis B strain ever found in the Americas.

In another man’s teeth (the one with the bad knees), Barquera and his colleagues found DNA from a bacterium called Treponema pallidum pertenue, a close relative of syphilis; it causes a disease called yaws. People with yaws suffer from painful inflammation in their bones, joints, and skin, and this man’s skeleton showed the scars of his life with the disease.

Yaws is a very contagious disease, easily spread by poor hygiene. And a European colonist who died in the 1600s in what is now Mexico City—not terribly far from the Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales—had been infected with the same strain. So along with their captive slaves, the Spanish colonists had imported a debilitating disease and suffered the consequences.

Humanizing the past

Several people enslaved in British colonies and the United States in the 1700s and 1800s wrote down their stories. Those slave narratives are tough, heartbreaking reads, but it’s something else entirely to confront the broken bodies of the victims. The story is no longer a story; it becomes real. And archaeological methods are, more and more often, allowing us to see that reality—and allowing the overlooked dead to speak for themselves.

“Interdisciplinary studies like this will make the study of the past a much more personal matter in the future,” said study coauthor Thiseas C. Lamnidis.

Current Biology, 2020 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub/2020.04.002 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1673582