As July came to a close, the Atlantic Ocean was absolutely sizzling, particularly in areas where hurricanes commonly form.

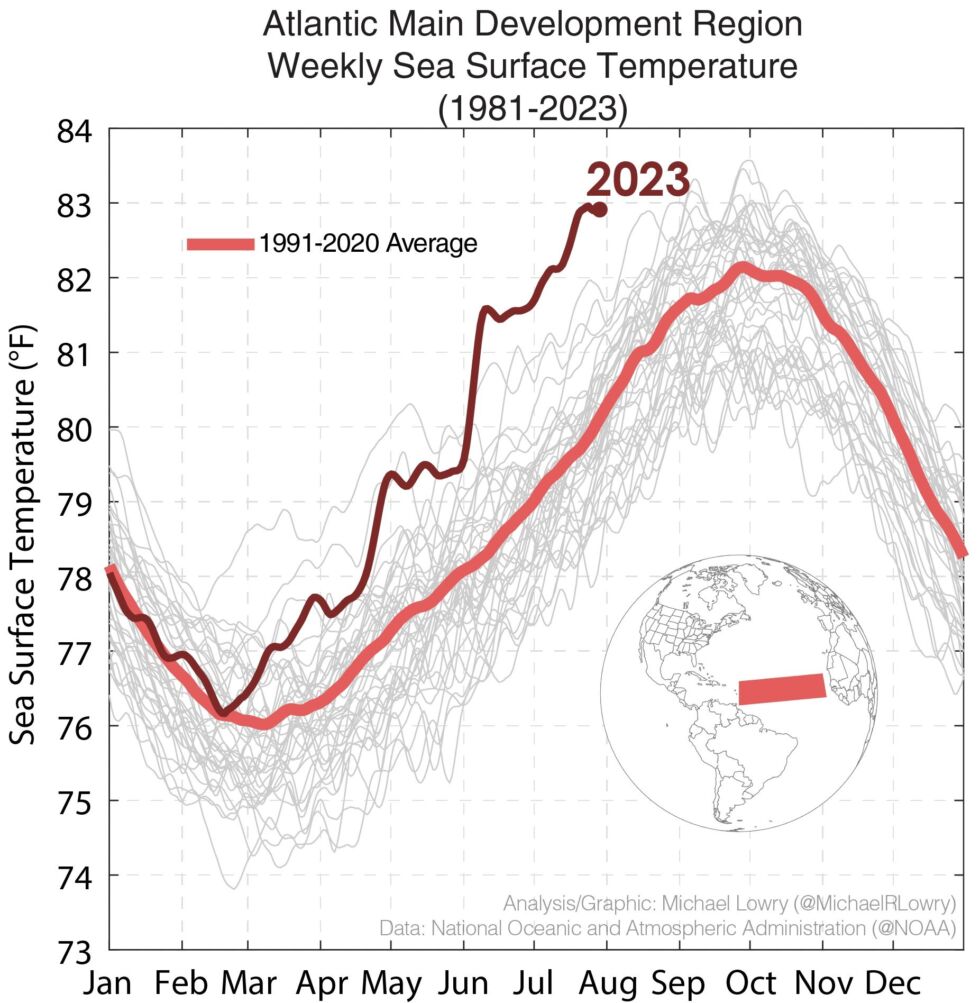

In the “main development region,” a stretch of tropical water between Africa and the Caribbean Sea where most major Atlantic hurricanes develop, the sea surface temperature averaged 82.4° Fahrenheit, a full degree above any previous July.

This kind of temperature, at least partly fueled by a changing climate, has only rarely been seen in past hurricane seasons—and then only during September or early October, when temperatures in the tropical Atlantic typically reach their peak.

And yet, overall, July was a fairly quiet month in the Atlantic tropics. There was just a single named storm, Don, in the middle of the month in the middle of the Atlantic—and it was of no consequence to anyone. Don was a hurricane, that is true. But it barely achieved hurricane status, at 75 mph for 12 hours, before rapidly weakening.

So if the Atlantic tropics are a bathtub capable of supporting major hurricanes, where are the storms? And what does this mean for the remainder of the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, which usually peaks in September?

Shearing the storms

The reality is that the Atlantic tropics are usually fairly quiet during June and July, and the overall activity this year is slightly above normal levels. Sea surface temperatures are one factor why hurricane season doesn’t really get spinning in a big way until August and September, but there is another factor to consider as well—wind shear.

Shear measures the variation in the velocity and direction of wind flow at various levels of the atmosphere. The more shear there is, the more turbulent the atmosphere. And the more turbulent the atmosphere, the more difficult it is for storms to form and strengthen. If wind shear is strong enough, it can literally shear the top of a hurricane off.

Shear levels are often fairly high during June and July in the Atlantic basin, and this also explains why tropics seasons often start slowly. When we look at wind shear values over the last month, they have been about normal across much of the Atlantic and particularly high in the Caribbean Sea, where storms historically have developed during July.

So in terms of activity, this year has been progressing pretty much as expected. Because we are in El Niño, we are seeing Atlantic wind shear levels near or above normal levels. That tends to suppress activity, which has happened despite the sizzling seas.

All well and good, but what happens now?

Looking into the future

That’s the big question. We’ve discussed sea surface temperatures, which are certain to remain sizzling for the coming season. This would support the notion of a historically active and dangerous hurricane season.

Then there is wind shear. Typically this would be higher during an El Niño year, but there is no guarantee. Indeed, as forecaster Michael Lowry pointed out in his Eye on the Tropics newsletter, some modeling indicates shear may relax toward the end of August. This is exactly what we don’t want to happen, as it likely would signal a burst in Atlantic hurricane activity.

Another impact of an El Niño year is sinking air, which inhibits the formation of storms because they’re fueled by moisture rising from the ocean. So far, we have seen plenty of sinking air in the Atlantic this year. But there is no reason to believe that will necessarily continue during the critical months of August and September.

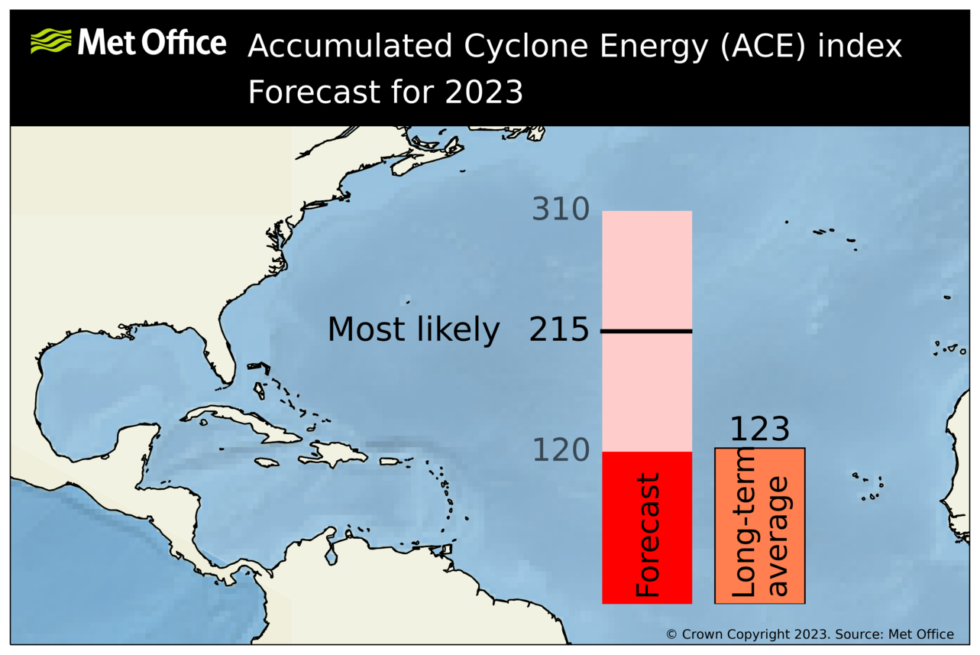

As a meteorologist and a Gulf Coast resident, I will say that I am watching the approach of the peak of this Atlantic hurricane season warily. The water temperatures are historically high, and the analog years like 2005—the year of major hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma—are sobering. Noted seasonal forecasters like Phil Klotzbach, of Colorado State University, have also been raising their expectations of activity this year. And just on Tuesday, the United Kingdom’s Met Office released a forecast calling for a very busy season indeed.

Putting all of this together, I am concerned, very concerned, about the next two months.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1958160