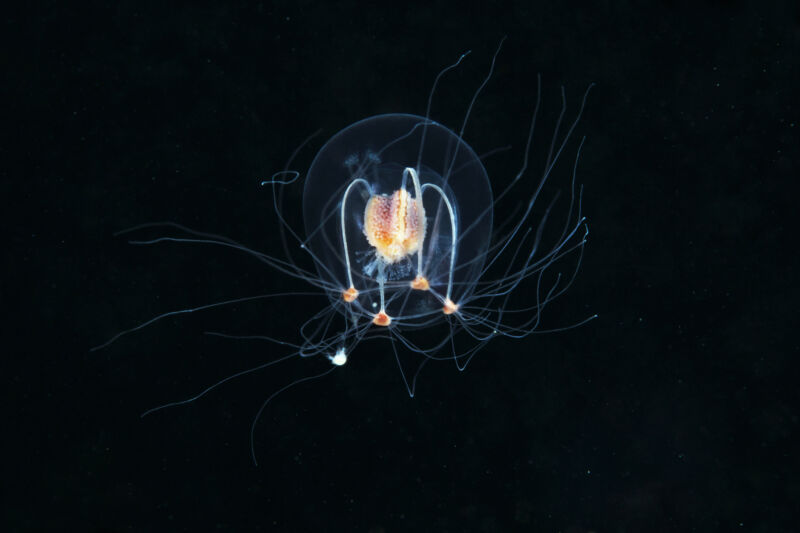

In the past, scientists thought of the deep ocean as a cold, dead place. While the region—generally considered to be everything between 200 and 11,000 meters in depth—is undoubtedly cold, it actually holds unexpected biodiversity.

“Back in the 1970s, there was this myth of the deep sea as this empty desert wasteland with nothing alive. For many years, we’ve known this is absolutely false,” Julia Sigwart, a researcher at the Senckenberg Research Institute in Germany, told Ars.

However, the abyss and the life within it remain poorly understood, despite making up around three-quarters of the area covered by the ocean. At this year’s United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15), Sigwart and her international colleagues presented a policy brief that urges more support for research into the biodiversity of the deep ocean, particularly as the region begins to be threatened by human activities.

Under the sea

According to the brief, around 28,000 deep-sea creatures have been identified and named, but its authors estimated that there are 2.2 million species that scientists have yet to identify—some of which are deep-sea species and/or are facing extinction. Some of them may go extinct before humans can even discover them.

“This is a huge portion of the Earth’s biological diversity that’s undiscovered and unnamed,” she said.

This is particularly worrying since the loss of some of these species could impact their respective habitats and other important biological functions in the ocean. The deep sea stores a great deal of the world’s carbon, so ecosystem upsets can have widespread consequences.

This is why Sigwart and her colleagues urged for more funding to understand and identify these species as the first and most obvious part of helping to conserve this area of the ocean. The first part of this program would simply be more expeditions, sending more missions with automated subs, cameras, etc., into the deep sea—an effort that doesn’t currently get a great deal of research funding or support, she said.

“Exploration is important, because there’s a lot of ocean, and there’s not so many of us doing the exploring,” she said.

Often, when deep-sea expeditions find new species, they’re quite small, like various worms or other critters that live in the sediment of the ocean floor. They’re small enough that they can’t necessarily be seen at a high enough resolution to determine what species they are—if they are even documented—on a hi-res camera or with the naked eye. And they lack the odd charisma that many other deep-sea species have, such as the angler fish or any of the other nightmarish creatures that glow in the deep. These somewhat less Lovecraftian creatures require more attention, she said.

Further, there’s little understanding of the natural range of deep-sea creatures. Quite often, knowledge of these species comes from a limited number of specimens, often taken from only a few sites. As such, it’s difficult to say how far these creatures may travel in their lives, creating an additional knowledge gap, Sigwart said.

“It’s the hard work part”

Discovering and tracking species, however, is only part of the equation. Sigwart noted that this is the exciting part of deep-sea research, so it gets a relatively high amount of support. But a good deal of work also takes place in the lab. The process of examining, dissecting, and describing these creatures, along with sequencing their DNA and determining if they are a distinct species, can take many lab hours and a lot of expertise, Sigwart said. She added that funding for this kind of work is also lacking. “It’s not the sexy part. It’s the hard work part,” she said.

Sigwart noted that furthering our understanding of the deep ocean is essential, particularly considering the rate at which humans are encroaching on the ecosystem. For instance, there’s now research looking into garbage like plastics, cloth, rubber, and fishing gear sinking to the depths.

Additionally, there’s a growing interest in deep-sea mining to gather various minerals such as nickel, copper, zinc, cobalt, and others used to create consumer electronics. It’s unknown how much this could impact deep-sea life and its ecosystems, but it possibility underlines the importance of better understanding these parts of the ocean.

“The reason we have a biodiversity crisis is because we as humans are so fixated on resources as something that’s there to exploit, not a part of the planet that it’s our moral obligation to protect,” she said.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1904138