Archaeologists have excavated a 5,300-year-old skull from a Spanish tomb and determined that seven cut marks near the left ear canal are strong evidence of a primitive surgical procedure to treat a middle ear infection. That makes this the earliest known example of ear surgery yet found, according to the authors of a recent paper published in the journal Scientific Reports. The Spanish team also identified a flint blade that may have been used as a cauterizing tool.

The excavation site is located in the Dolmen of El Pendón in Burgos, Spain, and consists of the remains of a megalithic monument dating back to the 4th century BCE, i.e., the late Neolithic period. The ruins include an ossuary holding the bones of nearly 100 people, and archaeologists have been excavating those remains since 2016.

In July 2018, the team recovered the skull that is the subject of this latest study. The skull was lying on its right side, facing the entrance of the burial chamber, and while most of the cranium was intact, no teeth remained. The missing teeth, plus the loss in bone density and fully ossified thyroid cartilage, indicated that this was the skull of an elderly woman aged 65 or older.

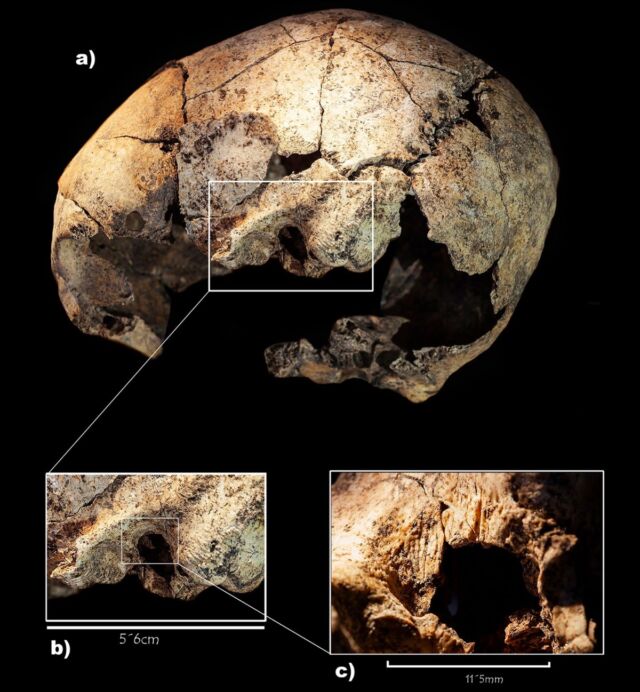

Evidence of perforations were found on both sides of the skull near the mastoid bones (located just behind the ear). The authors suggested that these perforations were the result of two surgical interventions, one on each ear, by someone with rudimentary anatomical knowledge. There was more bone remodeling on the right ear, indicting that the first surgery was performed to treat what was likely a life-threatening condition, given the risks associated with such a procedure during this period.

The woman survived the first procedure and endured a second surgery on the left ear sometime after. The authors were unable to determine whether the procedures were done back-to-back or whether months or even years passed between them. Regardless, “It is thus the earliest documented evidence of a surgery on both temporal bones and therefore, most likely, the first known radical mastoidectomy in the history of humankind,” they wrote.

This was a fairly common surgical procedure to treat acute ear infections by the 17th century, per the authors, and skulls showing evidence of a mastoidectomy have been found in Croatia (11th century), Italy (18th and 19th centuries), and Copenhagen (19th or early 20th century). Perhaps the oldest type of skull surgery is cranial trepanation—the drilling of a hole in the head—which has been well-documented along the Iberian Peninsula. Five skulls recovered from a site close to the Dolmen of El Pendón showed evidence of trepanation, and the individuals apparently survived those procedures, despite the lack of antibiotics and a high risk of complications.

What condition might have prompted such an intervention? The authors ruled out a cholesteatoma—an injury to the temporal bone that can cause hearing loss, vertigo, and other complications—even though this is one of the most well-documented diseases in pathological studies of ancient skulls. But cholesteatoma tends to erode the bony wall (scutum) separating the ear canal from the mastoid, and the scutum was intact on both sides of the woman’s skull. The authors also ruled out a bone tumor or malignant external otitis (a fast-spreading infection of the ear canal and temporal bone).

The authors concluded that the most likely condition was acute otitis media, aka a middle ear infection, which had spread to the underlying bone, specifically the mastoid bone (mastoiditis). The condition would have been easy enough to diagnose, since the infection causes visible swelling and redness as fluid and mucus build up inside the ear. If a middle ear infection spread to the mastoid bone, the bone’s honeycomb-like structure would have also filled with fluid and mucus. Untreated, this would have led to hearing loss and possibly meningitis. Mastoiditis resulting from a middle ear infection was one of the leading causes of death in children prior to the wide availability of antibiotics (and it is mercifully a rare condition today).

A modern mastoidectomy involves removing the cells in the mastoid bone’s hollow air-filled spaces. In a radical mastoidectomy, the surgeon will first make a cut behind the ear and then use a bone drill to open access to the middle ear cavity. Then the surgeon will remove any infected mastoid bone or tissue, stitch up the cut, and bandage the wound. Per the authors, their late Neolithic ear surgeon would have followed a similar (albeit much cruder) procedure, removing the affected bone to drain the middle ear and then connecting the mastoid bone with the tympanic cavity surrounding the bone of the inner ear.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1835516