A fossilized cranium of an extinct species of stargazer fish was stuffed with tiny fecal pellets known as coprolites, according to a recent paper published in the journal Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia—the first known skull in the fossil record to be completely filled with fecal pellets. This is a joint study by paleontologists at the University of Pisa in Italy, and the Calvert Marine Museum in Maryland, who proposed that tiny scavenging worms ate their way into the dead fish’s skull and pooped out the pellets.

It was a 19th century British fossil hunter named Mary Anning (recently portrayed by Kate Winslet in the 2020 film Ammonite) who first noticed the presence of so-called “bezoar stones” in the abdomens of ichthyosaur skeletons around 1824. When she broke open the stones, she often found the fossilized remains of fish bones and scales. A geologist named William Buckland took note of Anning’s observations five years later, suggesting that the stones were actually fossilized feces. He dubbed them coprolites.

Coprolites aren’t quite the same as paleofeces, which retains a lot of organic components that can be reconstituted and analyzed for chemical properties. Coprolites are fossils, so most organic components have been replaced by mineral deposits like silicate and calcium carbonates. It can be challenging to distinguish the smallest coprolites from eggs, for example, or other kinds of inorganic pellets, but they typically boast spiral or annular markings, and, as Anning discovered, often contain undigested fragments of food.

For archaeologists keen on learning more about the health and diet of past populations—as well as how certain parasites evolved in the evolutionary history of the microbiome—coprolites and paleofeces can be a veritable goldmine of information. For instance, last year we reported on an analysis of preserved paleo-poop revealing that the ancient Iron Age miners in what is now Austria were quite fond of beer and blue cheese.

In 2020, we reported on a new method (dubbed coproID) for determining whether fecal samples are human or were produced by other animals, particularly dogs. (Dog poo bears a strikingly close resemblance to human feces in both size and shape, is frequently found at the same archaeological sites, and has a similar composition). The method combines host DNA and gut microbiome analysis with open source machine-learning software.

If a coprolite contains bone fragments, chances are the animal who excreted it was a carnivore, and if there are tooth marks on those fragments, it can tell us something about how the animal may have eaten its prey. The size and shape of coprolites can also yield useful insights. If it’s spiral-shaped, for instance, the coprolite might have been excreted by an ancient shark, since some modern fish (like sharks) have spiral-shaped intestines.

This new joint study examined several fossil samples the museum’s collection containing coprolites. The fossils were recovered from the Calvert Cliffs in Maryland, with rocks formed from the sediment of the coastal ocean that once covered the region. The so-called Calvert Formation is a rich trove for fossil hunters, and while the cliffs are closed to the public, people regularly comb the beach for fossilized shark teeth, which are especially plentiful.

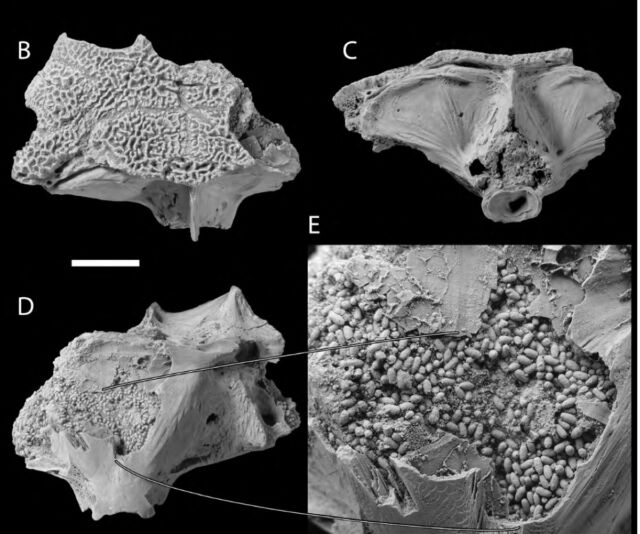

The most exciting of the fossils the scientists examined was the skull of an extinct species of stargazer fish called Astroscopus countermani, found in 2011 and dating back to the Miocene epoch. Today’s surviving Astroscopus species are venomous and can produce electric shocks. They hunt by camouflaging themselves and ambushing prey, and have been called “the meanest things in creation” by ichthyologist William Leo Smith.

The team identified two types of coprolites. The first were tiny micro-coprolites about 1/8th of an inch long and gray or brownish black in color. They were found in snail shells, clamshells, barnacles, and burrows, as well as the stargazer fish skull, usually stuffed into tiny spaces that shelled invertebrates wouldn’t have been able to access. So it’s likely they were deposited by small, soft-bodied worms—probably an annelid worm like a polychaete—who could have navigated those tight spaces.

There were also much larger coprolites found along the Calvert Cliffs, most likely fossilized crocodile dung, which showed evidence of tunneling by other animals. The authors suggest that the animals engaged in “coprophagy“: i.e., feces-eating, which sounds gross, but would have been an efficient means of recycling any nutrients present in the feces, as well as ensuring that the ocean floor wasn’t completely buried in feces.

The pellet-stuffed fish skull will be prominently featured at the Calvert Marine Museum’s inaugural Universal Coprolite Day on Sunday, February 20, 2022, described as a celebration of “excrement excitement.” Also on display: shark and fish-bitten coprolites, a coprolite preserving the impression of a baby turtle shell, and partially eaten coprolites, all demonstrating “the importance of coprolites in the fossil record and in the study of prehistoric life.”

DOI: Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 2022. 10.54103/2039-4942/17064 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1831979