When a German data recovery firm recently made a study of the failed flash storage drives it had been sent, it noticed some interesting, and bad, trends.

Most of them were cheap sticks, the kind given away by companies as promotional gifts, but not all of them. What surprised CBL Data Recovery was the number of NAND chips from reputable firms, such as Samsung, Sandisk, or Hynix, found inside cheaper devices. The chips, which showed obvious reduced capacity and reliability on testing, had their manufacturers’ logo either removed by abrasion or sometimes just written over with random text.

Sometimes there wasn’t a NAND chip at all, but a microSD card—possibly also binned during quality control—scrubbed of identifiers and fused onto a USB interface board. On “no-name” products, there is “less and less reliability,” CBL wrote (in German, roughly web-translated). CBL did find branded products with similar rubbed-off chips and soldered cards but did not name any specific brands in its report.

-

While most chips had their manufacturer’s name scratched off their seals, one cheap USB stick simply stamped enough capital-letter text over the name to make it unintelligible.

-

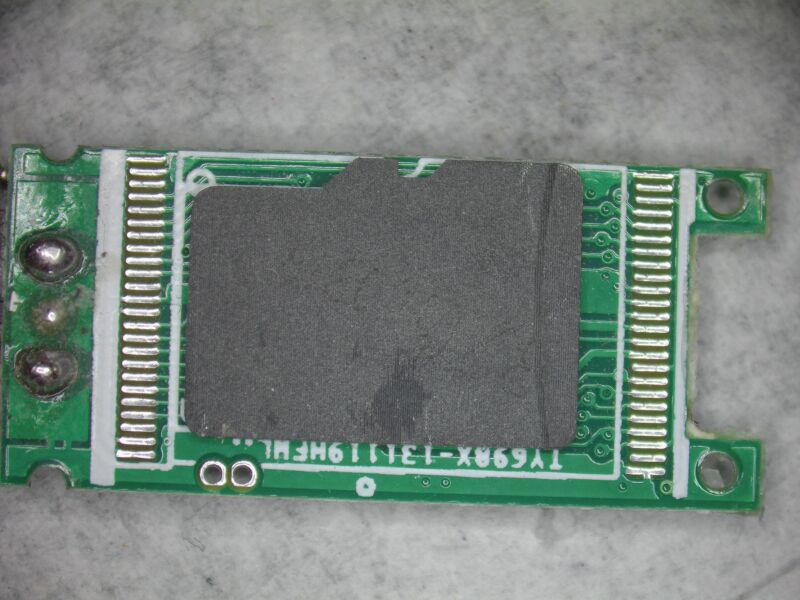

Detail on a NAND chip that has its make and original name removed by abrasion (look for the circular pattern in a pre-defined area on the chip cover).

Beyond obvious physical corner-cutting, a general trend in NAND storage cells has contributed to a lower overall reliability, according to CBL. SLC, or single-level cell storage, has one bit per cell, 1 or 0, which are two different voltage levels. A QLC (quadruple-level) chip uses four bits per cell, which means 16 voltage levels that must be correct. QLC allows for denser storage, but, as we noted previously: “As the data density of NAND cells goes up, their speed and write endurance decreases—it takes more time and effort to read or write one of eight discrete voltage levels to a cell than it does to get or set a simple, unambiguous on/off value.”

With high-quality chips, there’s a lot of work put in to correct errors and control temperatures. With chips that are not actually chips or were grabbed from the quality-control discard bin and scrubbed of their logo, “data loss is not surprising,” CBL writes.

All told, CBL’s report makes the case for never putting anything you really need to keep stored long-term on a USB stick. This might not be a revelation for those who have read up on proper storage practices, but CBL has further recommendations for those keeping anything at all on USB sticks:

- Keep them stored somewhere cool

- Don’t use promotional sticks for anything of any importance

- Write and read to a USB stick once or twice a year, to engage error correction (at least in higher-quality sticks)

- Don’t stuff the disk full, if you can avoid it, to give data maintenance and error correction a fighting chance.

The market for affordable, pocket-sized storage has proven itself to be a messy one over the last few years. High-capacity storage is, in fact, getting cheaper, but not in every corner—at least, not when you look closely. In mid-2022, a “30TB” external SSD was listed on Walmart and AliExpress for just over $30. Inside were two microSD cards, hot-glued to a USB 2.0 board and loaded with firmware that both misrepresents itself to Windows and simply rewrites its limited space over and over as you copy to it.

Similarly, a “16TB” SSD, listed for a relatively reasonable $70 and sporting dozens of five-star reviews, seemed to be actually 64GB worth of microSD cards, as Review Geek discovered. We noted a plethora of similar cons when we wrote about it, along with the problem of Amazon sellers’ ability to disappear as soon as the jig is up, only to reappear soon after with a new batch of microSD cards upsold with exponentially more faux-capacity.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=2001639