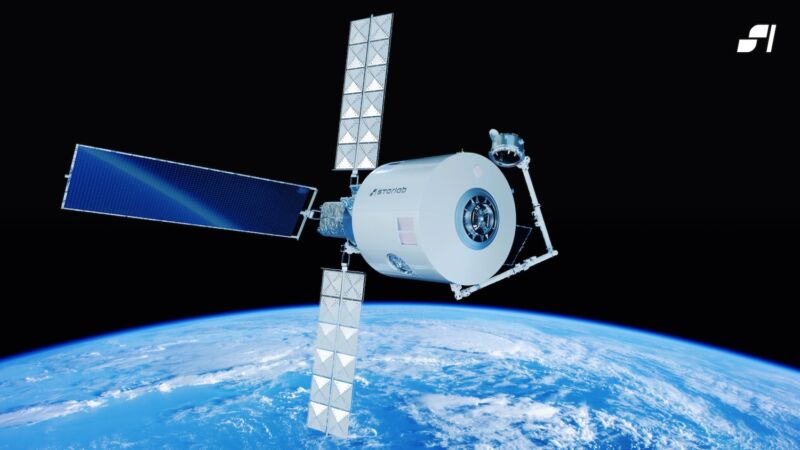

Voyager Space, one of several US companies formulating concepts for new commercial space stations, has established a joint venture with Airbus to co-develop an Earth-orbiting research outpost called Starlab.

The companies announced the joint venture Wednesday, saying they plan to field a successor to the International Space Station. “The US-led joint venture will bring together world-class leaders in the space domain, while further uniting American and European interests in space exploration,” the two companies said in a joint statement.

Voyager has been managing the development of a privately-owned space station called Starlab for several years. The Starlab station concept was one of three selected by NASA for funding in 2021, alongside with projects from separate industry teams led by Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman. Voyager’s proposal took home the largest NASA funding award—$160 million—to go toward design and engineering work for the Starlab station through a cost-sharing public-private partnership arrangement.

The European aerospace giant Airbus is now taking a larger role in the Starlab program. Following an announcement in January that Airbus was joining Voyager’s Starlab team, the joint venture unveiled this week cements Airbus as a co-owner of the space station. “With a track record of innovation and technological firsts, Airbus prides itself on partnering with companies that are looking to change history,” said Jean-Marc Nasr, head of space systems at Airbus, in a press release.

On station

Voyager is a Colorado-based holding company with a portfolio that includes Nanoracks, which helps facilitate access to the International Space Station for scientific experiments and technology demonstration payloads. Nanoracks also owns a commercial pressurized airlock module at the ISS to enable payloads to pass between the lab’s internal cabin and the outside environment of space.

NASA wants to have at least one commercial space station flying by the time the International Space Station is due for retirement in 2030, ensuring US astronauts and researchers can continue working continuously in low-Earth orbit. This strategy, NASA says, will allow government resources to focus on deep space exploration, such as the Artemis lunar program and eventual human missions to Mars.

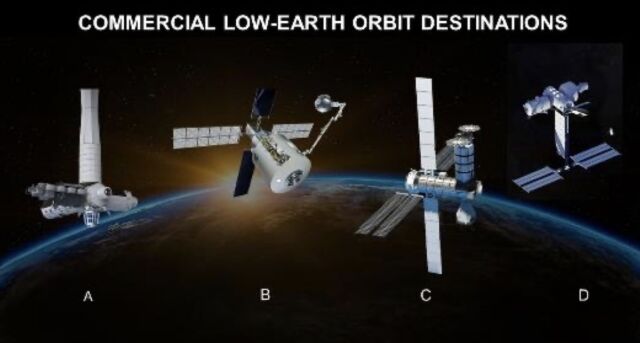

Aside from its agreements with Voyager, Blue Origin, and Northrop Grumman, NASA also has a partnership with Axiom Space, which is building a privately-owned module to be attached to the International Space Station in the next few years. Axiom envisions that module will eventually become the centerpiece of its own independent space station in orbit.

NASA plans to hold a competition in 2025 and 2026 for these would-be space station developers to submit final proposals to the space agency, which will select one or more winners for firm-fixed price service contracts. That’s a procurement model that is similar to the one NASA used to work with SpaceX and Boeing to develop private space taxis through the commercial crew program.

This competition will not be limited to the likes of Voyager, Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, and Axiom—which already have NASA funding agreements—any interested US company is able to apply. Other bidders could include SpaceX and Vast, which have their own concepts for privately-owned space stations. All of these orbiting outposts would be serviced with commercial crew and cargo vehicles, with NASA serving as an anchor customer along with commercial clients.

While there are lofty projections of a thriving commercial market in low-Earth orbit supporting everything from pharmaceutical research to space tourism, NASA’s competition is expected to cinch the business case for the winners. It could be a death knell for some of the losers.

Cornering the European market

With this partnership, Airbus is betting that Voyager will be one of the winners.

Matthew Kuta, Voyager’s president, told Ars that the Starlab joint venture will be US-led, making it eligible to compete for the NASA commercial space station contract. But the companies have not divulged their exact ownership shares.

Kuta said it’s important to maintain the trans-Atlantic partnership between NASA and ESA, particularly as their ties with Russia fray after the invasion of Ukraine. “I think, given what’s going on with Russia and Ukraine, and China is the only other country with a space station in orbit, this is a time that we should be getting closer to our partners and allies, not going with the US only,” Kuta said.

The European Space Agency is one of NASA’s biggest partners on the ISS. One of Airbus’ roles on Starlab will be to attract interest from ESA, which will also face a potential gap in low-Earth orbit research after the demise of the International Space Station.

“We think by partnering with Airbus in a private commercial space station where Voyager and Airbus own it, it’s a great way for us to continue the partnership that exists today between ESA and NASA, except in a commercial sense,” Kuta said in an interview. “The foundation is with Voyager and Airbus to expand that partnership. We do intend to bring in additional partners as well over the course of time.”

“This trans-Atlantic venture with footprints on both sides of the ocean aligns the interests of both ourselves and Voyager and our respective space agencies,” Airbus’s Nasr said in a statement. “This pioneers continued European and American leadership in space that takes humanity forward.”

“Voyager has a great relationship with ESA and many of the member states’ space agencies,” Kuta said. “But certainly, Airbus, as the largest aerospace and defense company in all of Europe, would have much better relationships than Voyager would. We think it’s a great opportunity for Airbus to be leading that, and really helping us figure out how we can best meet the customer demand of ESA and the other space agencies.”

Airbus was the prime contractor for ESA’s Columbus module at the International Space Station, and also owns an external research platform outside Columbus called Bartolomeo.

“There’s never been a Starlab built,” Kuta said. “It’s the first of its kind, just like any of the commercial space stations will be, but it’s definitely leveraging a lot of our joint heritage.”

Exit Lockheed, enter Airbus

Airbus will build the primary habitation module for the Starlab space station, replacing Lockheed Martin in this role. The change is not just a swap of contractors. It’s a shift in design philosophy.

Lockheed Martin originally was to have built an inflatable pressurized habitat for the Starlab space station, similar to the expandable modules once developed by the now-defunct Bigelow Aerospace. The Airbus-built module will be metallic and rigid in form.

Kuta said the redesign to the metallic module will result in a quicker development schedule and lower costs. The metallic habitat will be similar to those that already make up the International Space Station.

“One of the things that’s really important is speed,” Kuta said. “Metal modules are just much more proven out, they’re much more cost effective … An inflatable as a primary habitat has never flown in space.”

Although Voyager made the change to a rigid metal module several months ago, Kuta compared the uncertainties about the strength of an inflatable module to the engineering shortcomings that led to the fatal implosion of the Titan submersible on an expedition to the Titanic in June. “The safety certification standards for a primary living habitat, whether it’s a module that is metal or a kevlar inflatable, it’s a much higher certification safety standard, which means costs,” Kuta said. “Similar to the Titan, it’s very difficult to calculate the strength of an inflatable habitat because it’s multiple layers of kevlar. You don’t really know if one strand breaks, if it’s OK, or if it’s not.”

Lockheed Martin will remain a supplier in other areas for the Starlab station, Kuta said, without naming specifics. Officials are not done selecting subcontractors and manufacturers for all of Starlab’s elements.

The Starlab station is designed to accommodate a permanent crew of four people, plus a few more on a short-term basis. NASA anticipates requiring capacity for at least two astronauts permanently in low-Earth orbit in the 2030s after the decommissioning of the ISS, which currently supports a permanent crew of seven.

Voyager says the Starlab station could be ready for launch in 2028. The entire station will launch on a single heavy-lift rocket. Kuta said the Starlab team will announce a launch provider for the space station in the next couple of months.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1958766