There’s a steady flow of reports regarding the failures of the US education system. Read the right things and you’ll come away convinced that early grades fail to teach basic skills, later grades fail to prepare students for college, and colleges students fail so much that they can’t cope with the world outside the campus walls. But this week brought a bit of good news for one particular area: college-level computer science programs appear to be graduating some very competitive students.

This comes despite the fact that US students enter colleges behind their peers in other countries.

The work, done by an international team of researchers, compares US college seniors to those of three countries where US companies have outsourced some of their work: China, India, and Russia. All of these countries have a reputation for first-rate computing talent, with India and China developing large internal markets as well. Many students from these countries also come to study in the US, while Russia and China have been involved in cyber attacks against the United States and/or companies based here.

All of those factors makes them relevant countries to study. The research, however, doesn’t include other developed liberal democracies, which most closely resemble the United States. So the exact place of the US within the global landscape isn’t clear.

The reason so few countries were examined is that the researchers put so much effort into the countries they did look at. For the three countries, the researchers identified a total of 85 schools, a random mix of elite and less-than-elite schools. At these schools, they got students in their final year of a computer science undergraduate program to sit for a two-hour exam. The exam was translated into the local language and based on materials from the company responsible for administering the GRE tests used for graduate school admissions. All told, 678 Chinese students, 364 Indians, and 551 Russians took the exam.

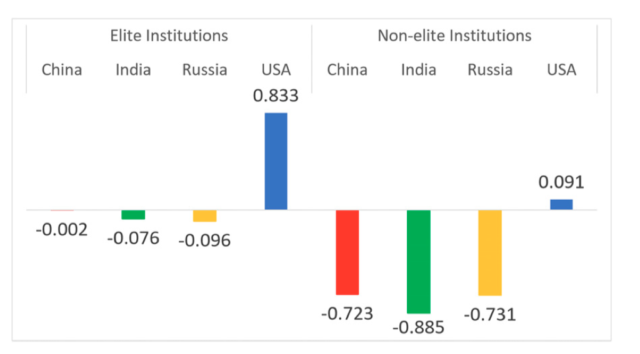

For US-based students, the results are promising. A comparison of undergraduate data indicates that US students enter college with lower math and physics scores as well as fewer physics classes than their counterparts overseas. By the time they graduate with computer science degrees, however, the US students score significantly better, coming about 0.76 standard deviations ahead of their international peers. There were no statistically significant difference among the students from other countries. The gap actually grows if students from elite universities are analyzed separately. (Students at these elite universities also outperformed their peers at lower-profile universities.)

One concern here is that the US is benefitting from getting some of the best foreign students, who inflate its scores. But the researchers corrected for this by separating out anyone who didn’t list English as their native language; the gap was unaffected.

Another issue the researchers looked at was the gap between males and females. In all countries, males tend to outperform females. But US-educated women outperformed everyone but US males. Even if you selected only males at elite colleges, the US-educated women did better. All of which suggests that both cultural and educational factors play significant roles in influencing the gender disparity. The authors also suggest that the small gap between male and female US graduates means that the reason for their subsequent pay disparities has to lie elsewhere.

In addition to the above caveat regarding the countries chosen for this analysis, there’s the issue of the tests themselves. The authors took great pains to ensure the translation of the test materials are top-notch. But the test questions themselves are focused on the US education system, as the GRE questions are designed based on surveys of US graduate and undergraduate programs. Thus, there’s a chance that some of these questions are skewed to favor the products of the US education system. The fact that Chinese, Indian, and Russian students all performed at similar level, however, suggests this probably wasn’t a major issue.

All told, the US produces about 65,000 students with computer science degrees each year, a number that’s gone up dramatically over the past few decades. That number is dwarfed by either China (185,000 students) or India (215,000 students). But the new research suggests those students are extremely well-prepared compared to those in other countries.

PNAS, 2019. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1814646116 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1479225