When RMS Titanic struck an iceberg on April 14, 1912, crew members sent out numerous distress signals to any other ships in the vicinity using what was then a relatively new technology: a Marconi wireless telegraph system. More than 1,500 passengers and crew perished when the ship sank a few hours later. Now, in what is likely to be a controversial decision, a federal judge has approved a salvage operation to retrieve the telegraph from the deteriorating wreckage, The Boston Globe has reported.

Lawyers for the company RMS Titanic Inc.—which owns more than 5,000 artifacts salvaged from the wreck—filed a request in US District Court in Alexandria, Virginia, arguing that the wireless telegraph should be salvaged because the ship’s remains are likely to collapse sometime in the next several years, rendering “the world’s most famous radio” inaccessible. US District Judge Rebecca Beach Smith concurred in her ruling, noting that salvaging the telegraph “will contribute to the legacy left by the indelible loss of the Titanic, those who survived, and those who gave their lives in the sinking.”

However, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is fiercely opposed to the salvage mission. The agency argues in court documents that the telegraph should be left undisturbed, since it is likely to be surrounded “by the mortal remains of more than 1500 people.” Judge Smith countered in her decision that the proposed expedition meets international requirements: for instance, it is justified on scientific and cultural grounds and has taken into account any potential damage to the wreck.

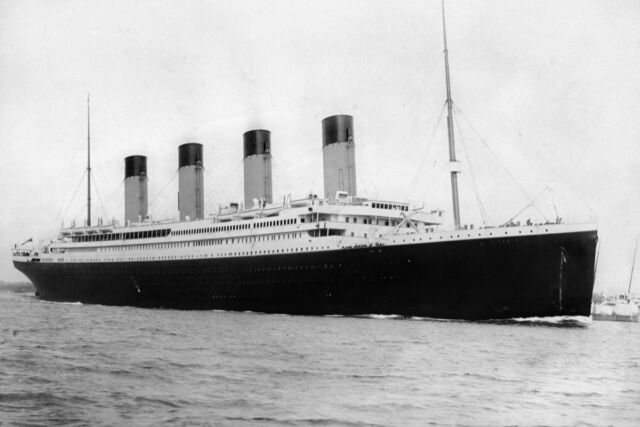

Titanic is by far the most famous historical shipwreck—even before James Cameron’s blockbuster 1997 film. Something about the tragedy holds an enduring fascination in the popular imagination. The ship set out on her maiden voyage to much fanfare on April 10, 1912. Cameron’s film recreated with impressive detail many of the liner’s luxurious features, including the grand staircase, opulent dining room, and gymnasium.

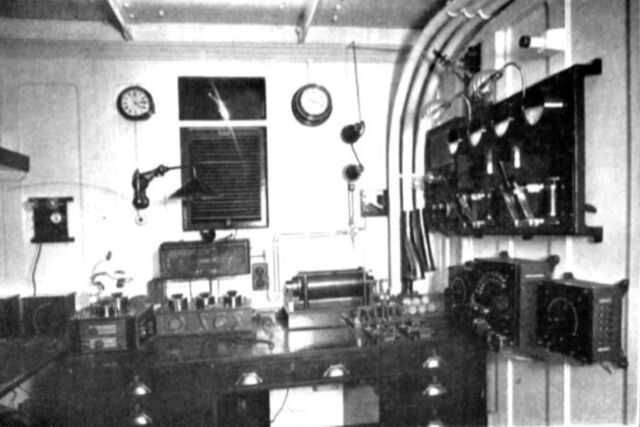

There was also a wireless telegraph system on board, courtesy of the Marconi International Marine Communication Company, capable of transmitting radio signals over a radius of 350 miles (563 kilometers). Although its purpose was mostly to send so-called “marconigrams” for the ship’s wealthiest first-class passengers, operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride also handled any messages from other ships—notably weather reports and ice warnings.

Radiotelegraphy was very much still a novelty at the time, although the very first rudimentary telegraph dates back to 1837. That’s when British physicists William F. Cooke and Charles Wheatstone developed a simple electrical switch with a pair of contact wires, controlled by a metal key. Pressing up and down on the key connected or disconnected the electrical circuit, transmitting the signal as a series of electric pulses, according to a predetermined code.

Within two years, their system was being used to send messages between local railway stations as much as 29 kilometers apart. (British police relied on the telegraph to help capture fugitive murderer John Tawell in 1845.) The Cooke-Wheatstone approach was ultimately superseded by the telegraph system created by the American inventor Samuel Morse, who also invented Morse Code.

But the Morse telegraph still required cables to function. The discovery of radio waves—first predicted by James Clerk Maxwell in 1867 and experimentally generated by Heinrich Hertz in 1887—opened up a whole new era for the telegraph. Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi was among the most noteworthy pioneers, developing practical radio transmitters (initially simple spark-gap transmitters) and receivers in 1894-1895.

Marconi kept improving on his devices, achieving ever-greater distances, and eventually moved to England to continue his work when it failed to attract attention and funding from the Italian government. Marconi successfully sent the first wireless telegraphic signals across the Atlantic Ocean in 1901.

That brings us back to Titanic, which met its doom just four days into the Atlantic crossing, roughly 375 miles (600 kilometers) south of Newfoundland. (In an odd historical twist, Marconi had been offered free passage on Titanic‘s maiden voyage but opted to travel on the Lusitania a few days earlier.) Phillips and Bride had been receiving ice warnings from other ships all day, beginning at 9:00am with reports of “bergs and growlers.” Captain Edward Smith shifted course a bit further south in response, but he didn’t reduce speed.

By late afternoon, the SS Californian had sent messages regarding “much heavy pack ice and great number large icebergs.” Alas, Captain Smith never received those later messages, apparently because an overworked Phillips was frantically trying to catch up on passenger marconigrams after a breakdown of the equipment the day before. In fact, Phillips’ response to the Californian‘s final warning was a frustrated, “Shut up! Shut up! I’m working Cape Race!” (referring to the relay station at Cape Race, Newfoundland). The Californian‘s radio operator then shut the system down for the night and retired to quarters.

At 11:40pm ship’s time on April 14, Titanic hit that infamous iceberg and began taking on water, flooding five of its 16 watertight compartments, thereby sealing its fate. As the lower compartments of the ship filled with water and the crew rushed to evacuate as many passengers as possible into the limited number of lifeboats before the ship sank, the wireless telegraph operator sent out a series of increasingly frantic Morse Code messages, including what has become the world’s best known distress signal: dot dot dot dash dash dash dot dot dot (SOS). Only around 710 of those on board survived the sinking.

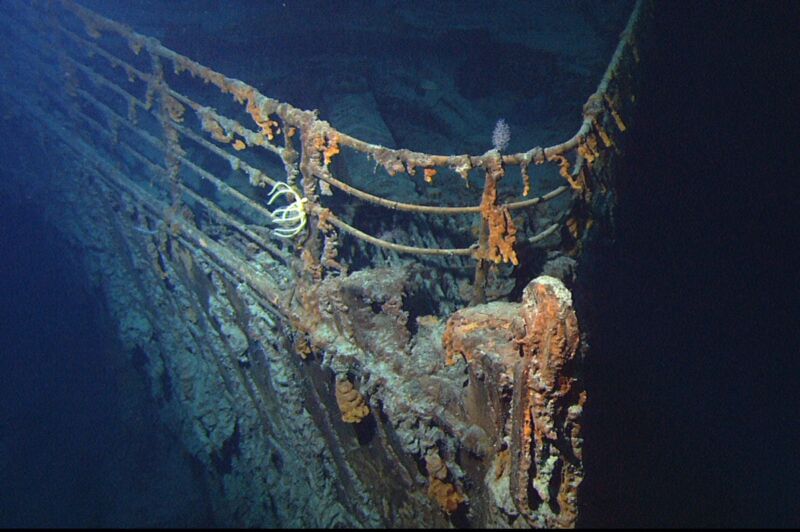

Titanic remained undiscovered at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean until an expedition led by Jean-Louis Michel and Robert Ballard reached the wreck on September 1, 1985. The ship split apart as it sank, with the bow and stern sections lying roughly one-third of a mile apart. The bow proved to be surprisingly intact, while the stern showed severe structural damage, likely flattened from the impact as it hit the ocean floor. There is a debris field spanning a 5×3-mile area, filled with furniture fragments, dinnerware, shoes and boots, and other personal items.

Many thousands of surviving artifacts have been salvaged over the years by various groups and have subsequently featured in touring expeditions. But this practice is not without controversy, particularly concerning the salvaging activities of RMS Titanic Inc. There are those who want to recover and preserve as many artifacts as possible for posterity (“conservationists”), while a rival group, including Ballard, considers any disturbance of the wreck to be a disrespectful violation (“protectionists”).

The conservationists have won out in recent years, despite the fact that RMS Titanic Inc. apparently destroyed the ship’s crow’s nest when it retrieved Titanic‘s bell. But the wreck has been deteriorating badly, and not just from accidental damage by salvage operations. (A two-person submersible crashed into the wreck just last year.) Deterioration is also due to iron-munching bacteria feasting on the ship’s hull. So there’s a sense of urgency driving salvage efforts.

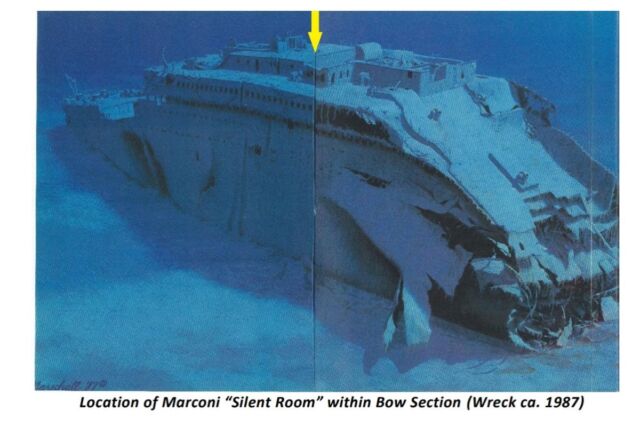

This latest ruling is bound to generate more controversy, given that the expedition’s plans call for “surgically” removing the telegraph from the hull, risking further damage. (It’s believed that the telegraph is located in a deck house near the grand staircase.) According to an Associated Press report, the company’s 60-page plan calls for an uncrewed submersible to pass through a skylight. If that doesn’t work, the expedition would cut through the roof, which is already heavily corroded. Then a “suction dredge” will remove any loose silt, and the submersible’s arms will cut through any electrical cords.

Slated for August of this year, the team intends to take the opportunity to evaluate how well the wreckage is holding up, with particular attention on that part of the wreck housing the Marconi telegraph, according to oceanographer and Titanic expert David Gallo. Now retired from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Gallo is a consultant to RMS Titanic Inc.

“Previously, entering the hull of Titanic, cutting into the hull, or removing items from the hull were strictly prohibited,” Gallo told The Boston Globe. “If we agree that the telegraph is in imminent danger of being lost forever, and if we agree that the telegraph can be extracted surgically without unnecessary damage to the Titanic, we will be prepared to do so.”

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1679252