When you hear the name Crash Bandicoot, you probably think of it as Sony’s platformy, mascoty answer to Mario and Sonic. Before getting the full Sony marketing treatment, though, the game was developer Naughty Dog’s first attempt at programming a 3D platform game for Sony’s brand-new PlayStation. And developing the game in 1994 and 1995—well before the release of Super Mario 64—involved some real technical and game design challenges.

In our latest War Stories video, coder Andy Gavin walks us through a number of the tricks he used to overcome some of those challenges. Those include an advanced virtual memory swapping technique that divided massive (for the time) levels into 64KB chunks. Those chunks could be loaded independently from the slow (but high-capacity) CD drive into the scant 2MB of fast system RAM only when they were needed for Crash’s immediate, on-screen environment.

The result allowed for “20 to 30 times” the level of detail of a contemporary game like Tomb Raider, which really shows when you look at the game’s environments. Similar dynamic memory management techniques are now pretty standard in open-world video games, and they all owe a debt of gratitude to Gavin’s work on Crash Bandicoot as a proof of concept.

-

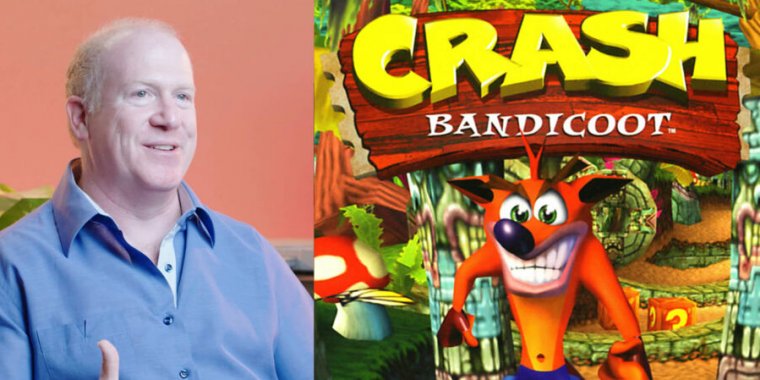

Behind the scenes at the video shoot with Crash Bandicoot creator Andy Gavin.

-

A camera-operator’s-eye-view of the shooting process.

-

Our Crash set, sans Andy.

-

Revel in Ars Creative Director Aurich Lawson’s latest glorious Ars logo photochop!

Squeezing memory for stretchy animation

Getting expressive, stretchy Warner Bros.-style animation was also a priority for Gavin and partner Jason Rubin—so much so that Crash himself used up 600 of the 1,500 polygons they got the PlayStation to render for every animation frame. But those characters would still look too stiff if they used the standard “skeletal” 3D animation of the day, which layered body part on top of virtual “bones” that moved a bit robotically.

To get around that, the Naughty Dog team pre-baked and stored positional animation data for all of Crash’s 500 different vertices across every in-game animation. Getting all that data to fit on the PlayStation’s limited hardware, though, involved writing a custom compression algorithm that threw out unnecessary data for vertices that didn’t move as much. The result was a “50 or 80 to 1 compression,” Gavin recalls, a huge savings that allowed for much more fluid and cartoonish animations.

Watch the full video for more stories about how Naughty Dog hacked the PlayStation’s built-in code libraries to their bone to maximize the available memory and mathematical speed on the largely untested hardware. Also tune in to figure out which dimension the team decided to restrict in order to avoid the “empty space” problem inherent in many early 3D platformers (hint: it’s a dimension the characters in Doctor Who have a lot of experience manipulating).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1656632