Severed heads. Skulls on stakes. Surfers in a gun battle. A bridge rebuilt and blown up every night. Painted faces. A jungle swallowed in flame. Wagner. The Doors. Sweat. Malaria. And so many helicopters, their blades pounding relentlessly. Only Crazy Grenade-Launcher man knows “who’s in charge here,” and he ain’t saying.

Yes, Apocalypse Now is back. For its 40th anniversary, the movie has been remastered in 4K digital and re-edited before heading to Blu-ray and 4K/Ultra HD discs. The nightmarish Vietnam War epic is the quintessential example of the “cinema of endurance”: long, grueling, magnificent, and LOUD. When Apocalypse Now first hit theaters in 1979, it ran about 2.5 hours, but its 2001 re-release (dubbed Apocalypse Now Redux and presented in 35mm) clocked in at a whopping 3 hours and 22 minutes. The newest version, Apocalypse Now Final Cut, comes in at about 3 hours.

-

Martin Sheen stars as Captain Willard. Sheen is best known for being Paula Abdul’s father-in-law from 1992 to 1994.

-

The roar of these birds will be drilled into you.

-

Robert Duvall as Lt. Col. Kilgore commands his subordinates.

-

The Patrol Boat, River, (or PBR) codenamed Street Gang that carries Our Guys upriver.

-

Duvall, Sheen, and Albert Hall (as Chief Phillips) relax for a bit.

-

This dude did not come to play.

-

Dennis Hopper at maximum Dennis Hopper-ness.

-

Marlon Brando as my neighbor Totoro.

-

Snazzy new poster.

The Sony 4K Laser

Before heading to home video, Final Cut gets a brief theatrical run so you can watch it the way God and Director Francis Ford Coppola intended: on a huge screen in a dark room with no ability to hit pause and escape. Many theaters are also showing it on Sony’s cutting-edge 4K Laser Cinema Projectors, which only hit the market about a year ago. Although most cinema projectors are already 4K, the 4K Laser replaces the xenon bulbs used by most projectors with a longer-lasting, brighter, and more-consistent laser.

I hadn’t seen Apocalypse Now all the way through since Redux in 2001, and I’d never seen a movie in 4K Laser or even heard those words put together before. So I leapt at the opportunity to see the movie again in a newer fidelity. And not only did I get to see Final Cut at the Alamo Drafthouse LaCenterra just outside Houston, but manager Robert Saucedo and projectionist Noah Fife were generous enough to show me their Sony 4K Laser. And while the 4K Laser may lack the old-school romance of Alamo Austin’s 70mm projector, I learned plenty about modern digital cinema presentation.

Like the vast, vast majority of big-budget productions from the 20th century, Apocalypse Now was shot on 35mm film, whereas more and more movies today are being shot on a combination of 2K, 4K, and even 8K digital cameras. Anyone who has suffered through five minutes of conversation with me knows that I’m sniffy about movies shot on film being projected digitally. So let’s find out more about the 4K Laser before we see how well it can manage the smell of napalm in the morning.

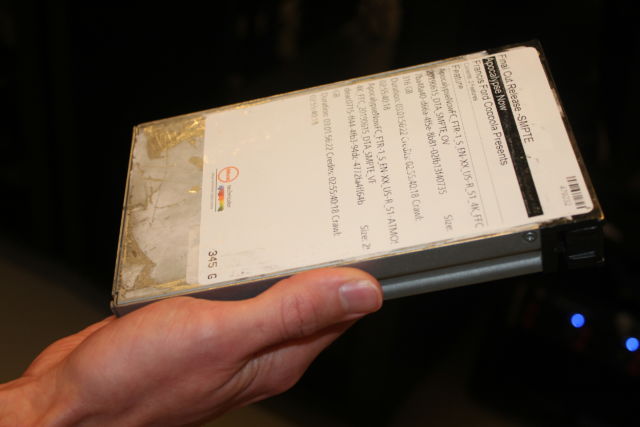

Apocalypse Now Final Cut (yes, the official title has no colon) arrived on the single hard drive pictured above. “This one’s about 345GB, which is pretty big, partly because it’s 4K,” says projectionist Noah Fife. “Usually a 2K movie, they average about 150GB. [4K] is four times the resolution of a 1080p or 2K image. It’s gonna be a much larger file. Lots of detail and plot in there.”

Remember to tip your server

-

Movies downloaded via satellite go directly into this server located in one of the Drafthouse’s forbidden rooms. The server also accepts hard drives, or the hard drives can be copied directly to the digital projectors. Any projector can play any movie that’s on this server. (Not pictured: the two other servers that run the restaurant part of Drafthouse LaCenterra.)

-

I don’t pretend to understand what any of that stuff does.

-

These unopened boxes contain the kind of xenon bulbs that most projectors (both film and digital) use. Most commercial digital cinema projectors show 4K, but the biggest innovation with the Sony 4K Laser is that it uses a laser instead of these bulbs. (I was expecting “laser” to just be marketing, so imagine my surprise.)Joanna Opaskar

-

Here’s a peek at the software Alamo uses to schedule its showings.Joanna Opaskar

Although digital movies used to always arrive at theaters on hard drives, physical media are now mostly only used for older films. Meanwhile, new releases are plucked from the ether using the satellite dish on the theater’s roof. “We have another separate server that downloads stuff over the Internet,” Fife adds, “which saves on shipping costs, and we don’t have as many drives to worry about returning.”

Regardless of whether a movie arrives via satellite or hard drive, it shows up as an encrypted DCP (digital cinema package) file. The theater is not able to play it until the studio sends a key file that unlocks the DCP. “And once you have those keys, during the period the keys are active, you can play the movie as many times as you want,” says Fife. The studios “usually only give you keys for a week at a time. So every week we get updated keys. And they usually don’t unlock until about 24 hours before, which gives us enough time to put it on screen and tech-check it before you have any guests in the theater. But they usually don’t give it to you too early because they don’t want to have a week-early advanced screening or something like that.”

The projector itself

-

Like all the Drafthouse’s projectors, the Sony 4K Laser sits in a long corridor above the auditoriums where lighting is terrible, and photographs are a challenge. And…

-

… the professional photographer I hoped to bring with me to take pictures couldn’t make it. This image of yours truly sums up my photographic skills. Bear with me. [Editor’s note: THAT HAIR THO]Joanna Opaskar

As you can see from the picture, the Sony 4K Laser is divided into two big metal boxes. The top box is the projector.

Fife says, “The main image quality difference between older projectors and the 4K Laser is the light source.” The 4K Laser “is gonna look a lot nicer just because it can go a lot brighter than the xenon can, even though they’re both 4K… If you were to watch a dark scene in a movie on this projector and one of our older projectors, you could definitely be able to tell a difference.” That additional brightness also “makes them ready for HDR—high dynamic range.

“Since it has a laser instead of a xenon bulb, it has a much higher contrast ratio,” Fife continues. “I think it’s 15,000:1, and for our [projectors] with the xenon bulb, it’s 2,000:1. So this has five times better contrast ratio than one of our bulb projectors. What that means is that, whenever you’re watching a dark scene, it’s gonna have a lot blacker blacks than a projector with a xenon bulb would. It’s really gonna excel at showing dark scenes in movies like that. Like if you’re in the theater and the lamp is on but I don’t have anything playing, you can look at the screen and hardly even tell that the lamp is on.”

In addition to avoiding changing bulbs every couple of months, the laser will shine brightly for up to eight years. Even then, “it’s only supposed to lose 20% of its brightness,” Fife says. “[It’s a] pretty long time. Guess we’ll find out in eight years.”

The bottom box of the 4K Laser stores movies.

“You can put a hard drive in there,” says Fife. “It can load a movie in 20 minutes. Even a huge, 200GB file. On the older ones, it takes a little bit more time—like an hour or so.”

-

Projectionist Noah Fife stands next to the water-cooling system that keeps the 4K Laser from overheating. Older projectors use an exhaust tube that goes up to the ceiling. “This is constantly pumping water through the inside of the projector to keep everything nice and cool,” Fife says. “It’s a lot quieter than some of our older projectors because it doesn’t have as many fans running.”Peter Opaskar

-

This is all used for audio. When Apocalypse Now is playing, these machines want blood coming out of your ears.Peter Opaskar

-

This small camera is “consistently feeding information back to the projector,” says manager Robert Saucedo. Fife added that the camera “fixes the uniformity. Because over time, the edges of the screen will get a little dimmer than the center of the screen. So that camera is constantly running and calibrating the projector to make sure that the edges of the picture always stay as bright as the center of the picture. So it’s nice and uniform across the whole screen. So if I were to just put up a white image, it should look like pure white all across the screen, with no dimming around the edges.”

-

The light meter in action during a showing of The Lion King. This picture might be illegal.Joanna Opaskar

-

The fun-loving folks at Alamo have shelves of props, costumes, and toys to go along with special screenings.Peter Opaskar

-

Must be Italian.Joanna Opaskar

-

Manager Robert Saucedo introduces Apocalypse Now Final Cut and reminds us to keep our fool mouths shut during the movie. The audience obeyed.Joanna Opaskar

-

Joanna Opaskar

After all that, I got a drink and a snack and found my seat.

“Operating without any decent restraint”

The plot of Apocalypse Now is the same across all three cuts: Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) is sent upriver to stop a rogue Special Forces colonel (Marlon Brando) who has gone off his rocker and set himself up as a deity in command of a private army. (Or is it downriver? Never mind.) Willard’s orders are to terminate Colonel Kurtz’s command with extreme… something, I can’t remember. As we go upriver, things get progressively more insane, and the dialogue gets more quotable. The river-cruise-into-madness and the name “Kurtz” are both lifted from Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness about the colonial ivory trade in Africa.

The result is an audio-visual bonanza told on a huge canvas, alternately psychedelic, baffling, gorgeous, soul-crushing, and hilarious. The first 30 to 45 minutes are dominated by the sound of helicopters, with explosions, opera, and incomprehensible radio voices regularly adding to the cacophony. Even in “quiet” dialogue scenes, you can still hear the choppers in the distance, beating the air and pummeling you into submission. Distant strobe lights constantly cut through the night, while daytime skies stream with the apocalyptic work of far-off explosions. Smoke is always rising from somewhere.

Critics of Apocalypse Now have decried it as an intellectual muddle, and it might be, but it’s still an incredible experience. Sometimes you aren’t looking for a cogent philosophical statement as much as you want “GRRRR, MOVIE!!!”

“This is the end”

So how do I think Final Cut did at Alamo? The last time I saw Apocalypse Now was when Redux was playing in 35mm at the AMC Dunvale. That was in 2001, and what I most remember are the oranges—the fires, the explosions, the sunlight, the sky—being deep and rich. But this is hardly a side-by-side comparison.

At the Drafthouse, the dark scenes were crisp, the audio was spectacular, the audience behaved itself, the crispy cauliflower was out of this world, and my beer was cold. As for the daylight scenes, where digital projection tends to struggle? That might come down to personal preference. Would I prefer to see a beat-up 35mm print over a pristine digital projection?

Maybe? I’m like a terrible father who will tolerate all the scratches and dirt from his favorite child but will literally criticize his other kids for being too perfect. I’m the worst.

Also, there’s every possibility that, one day, you could show me a movie in the latest cutting-edge digital projector and just tell me that it’s a new 35mm print, and I might leave saying “That looked so great! Can’t beat film!” Which I guess makes me the one with an extreme prejudice.

Anyway, I’m looking forward to returning to the Drafthouse the next time the 4K Laser is showing a movie that was shot digitally. And I spy with my little eye that A Hidden Life was shot on RED digital cameras…

Listing image by Lionsgate

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1559885