Forget all those amusing memes of Anya Taylor-Joy’s Beth Harmon from The Queen’s Gambit facing off against Spock in Star Trek‘s infamous 3D chess. We want to see Beth take on challengers in a quantum chess tournament. The world’s first such tournament was held December 9 as part of the virtual Q2B conference on quantum computing, with Amazon’s Aleksander Kubica emerging victorious, New Scientist reports.

What exactly is quantum chess? It’s a complicated version of regular chess that incorporates the quantum concepts of superposition, entanglement, and interference. “It’s like you’re playing in a multiverse but the different boards [in different universes] are connected to each other,” said Caltech physicist Spiros Michalakis during a livestream of the tournament. “It makes 3D chess from Star Trek look silly.”

Quantum chess (as played in the tournament) is the brainchild of Chris Cantwell of Quantum Realm Games. When he was a graduate student in quantum computing at the University of Southern California, he got the idea while working on a project for a class on creativity and invention. “My initial goal was to create a version of quantum chess that was truly quantum in nature, so you get to play with the phenomenon,” Cantwell told Gizmodo back in 2016. “I didn’t want it to just be a game that taught people quantum mechanics.” By playing the game, the player slowly develops an intuitive sense of the rules governing the quantum realm. In fact, “I feel like I’ve come to more intuitively understand quantum phenomena myself, just by making the game,” he said.

To help launch a Kickstarter campaign for a commercial version of quantum chess, Alex Winter (i.e., Bill of Bill and Ted), directed a short video, Anyone Can Quantum (embedded below), in which Paul Rudd—who went subatomic and visited the quantum realm in Ant Man—challenged the late Stephen Hawking to a game of quantum chess. The video featured not only Rudd and Hawking matching wits but also an amusing voiceover by Keanu Reeves (i.e., Ted of Bill and Ted). It made its debut in January 2016 at One Entangled Evening, a special event to kick off a Caltech conference on the future of quantum computing. The 12-minute video has since racked up more than 8 million views.

You don’t need to be a quantum physicist to play quantum chess, per Cantwell, although it does help to already know the rules of regular chess. In quantum chess, there are multiple boards on which the pieces exist, and their number is not fixed. Players can perform “quantum moves” as well as regular chess moves; players just need to indicate which type of move they’re performing. Any quantum move will create a superposition of boards (doubling the number of possible boards in the superposition with each quantum move), although the player will see a single board representing all boards at the same time. And any individual move acts on all boards at the same time.

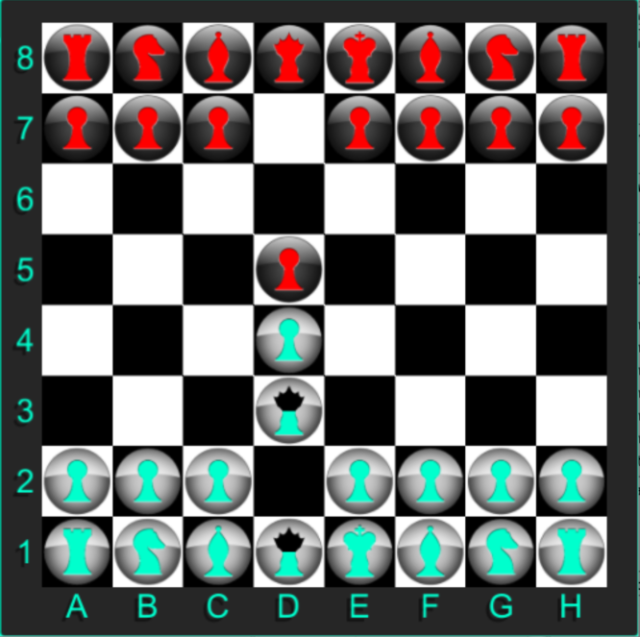

Pawns move the same as in regular chess, but other pieces can make either standard moves or quantum moves, such that they can occupy more than one square simultaneously. In a 2016 blog post, Cantwell offered the example of a white queen performing a quantum move from D1 to D3:

We get two possible boards. On one board the queen did not move at all. On the other, the queen did move. Each board has a 50 percent chance of “existence”. Showing every possible board, though, would get quite complicated after just a few moves. So, the player view of the game is a single board. After the same quantum queen move, the player sees this:

The teal colored “fill” of each queen shows the probability of finding the queen in that space; the same queen, existing in different locations on the board. The queen is in a superposition of being in two places at once. On their next turn, the player can choose to move any one of their pieces.

Pieces can also be entangled with each other—critical to Rudd’s strategy against Hawking. In order to determine where the entangled piece is actually located, a player must make a measurement. In fact, that’s the only way to win a game of quantum chess, since there is no check or check mate possible. A player must capture their opponent’s king as they make a quantum measurement of its location. The tournament games were timed, however, which is how Kubica eventually prevailed over his opponent, Google’s Doug Strain. Strain simply ran out of time.

And yes, Alex Winter remains a fan of quantum chess. “This idea of bridging quantum with something that’s a more understandable, practical game that people still invest a lot of thought into is, I thought that was really incredible,” he said during a surprise visit to the tournament livestream last week.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1729594