For centuries, Western scholars have touted the fate of the native population on Easter Island (Rapa Nui) as a case study in the devastating cost of environmentally unsustainable living. The story goes that the people on the remote island chopped down all the trees to build massive stone statues, triggering a population collapse. Their numbers were further depleted when Europeans discovered the island and brought foreign diseases, among other factors. But an alternative narrative began to emerge in the 21st century that the earliest inhabitants actually lived quite sustainably until that point. A new paper published in the journal Science Advances offers another key piece of evidence in support of that alternative hypothesis.

As previously reported, Easter Island is famous for its giant monumental statues, called moai, built some 800 years ago and typically mounted on platforms called ahu. Scholars have puzzled over the moai on Easter Island for decades, pondering their cultural significance, as well as how a Stone Age culture managed to carve and transport statues weighing as much as 92 tons. The first Europeans arrived in the 17th century and found only a few thousand inhabitants on a tiny island (just 14 by 7 miles across) thousands of miles away from any other land. Since then, in order to explain the presence of so many moai, the assumption has been that the island was once home to tens of thousands of people.

But perhaps they didn’t need tens of thousands of people to accomplish that feat. Back in 2012, Carl Lipo of Binghamton University and Terry Hunt of the University of Arizona showed that you could transport a 10-foot, 5-ton moai a few hundred yards with just 18 people and three strong ropes by employing a rocking motion. In 2018, Lipo proposed an intriguing hypothesis for how the islanders placed red hats on top of some moai; those can weigh up to 13 tons. He suggested the inhabitants used ropes to roll the hats up a ramp. Lipo and his team later concluded (based on quantitative spatial modeling) that the islanders likely chose the statues’ locations based on the availability of fresh water sources, per a 2019 paper in PLOS One.

In 2020, Lipo and his team turned their attention to establishing a better chronology of human occupation of Rapa Nui. While it’s generally agreed that people arrived in Eastern Polynesia and on Rapa Nui sometime in the late 12th century or early 13th century, we don’t really know very much about the timing and tempo of events related to ahu construction and moai transport in particular. In his bestselling 2005 book Collapse, Jared Diamond offered the societal collapse of Easter Island (aka Rapa Nui), around 1600, as a cautionary tale. Diamond controversially argued that the destruction of the island’s ecological environment triggered a downward spiral of internal warfare, population decline, and cannibalism, resulting in an eventual breakdown of social and political structures.

Challenging a narrative

Lipo has long challenged that narrative, arguing as far back as 2007 against the “ecocide” theory. He and Hunt published a paper that year noting the lack of evidence of any warfare on Easter Island compared to other Polynesian islands. There are no known fortifications, and the obsidian tools found were clearly used for agriculture. Nor is there much evidence of violence among skeletal remains. He and Hunt concluded that the people of Rapa Nui continued to thrive well after 1600, which would warrant a rethinking of the popular narrative that the island was destitute when Europeans arrived in 1722.

For their 2020 study, the team applied a Bayesian model-based method to existing radiocarbon dates collected from prior excavations at 11 different sites with ahu. That work met with some mixed opinions from Lipo’s fellow archaeologists, with some suggesting that his team cherry-picked its radiocarbon dating—an allegation he dismissed at the time as “simply baloney and misinformed thinking.” They filtered their radiocarbon samples to just those they were confident related to human occupation and human-related events, meaning they analyzed a smaller subset of all the available ages—not an unusual strategy to eliminate bias due to issues with old carbon—and the results for colonization estimates were about the same as before.

The model also integrated the order and position of the island’s distinctive architecture, as well as ethnohistoric accounts, thereby quantifying the onset of monument construction, the rate at which it occurred, and when it likely ended. This allowed the researchers to test Diamond’s “collapse” hypothesis by building a more precise timeline of when construction took place at each of the sites. The results demonstrated a lack of evidence for a pre-contact collapse and instead offered strong support for a new emerging model of resilient communities that continued their long-term traditions despite the impacts of European arrival.

Fresh evidence

Now Lipo is back with fresh findings in support of his alternative theory, having analyzed the landscape to identify all the agricultural areas on the island. “We really wanted to look at the evidence for whether the island could in fact support such a large number of people,” he said during a media briefing. “What we know about the pre-contact people living on the island is that they survived on a combination of marine resources—fishing accounted for about 50 percent of their diet—and growing crops,” particularly the sweet potato, as well as taro and yams.

He and his co-authors set out to determine how much food could be produced agriculturally, extrapolating from that the size of a sustainable population. The volcanic soil on Easter Island is highly weathered and thus poor in nutrients essential for plant growth: nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium primarily, but also calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. To increase yields, the natives initially cut down the island’s trees to get nutrients back into the soil.

When there were no more trees, they engaged in a practice called “lithic mulching,” a form of rock gardening in which broken rocks were added to the first 20 to 25 centimeters (about 8 to 10 inches) of soil. This added essential nutrients back into the soil. “We do it ourselves with non-organic fertilizer,” said Lipo. “Essentially we use machines to crush rock into tiny pieces, which is effective because it exposes a lot of surface area. The people in Rapa Nui are doing it by hand, literally breaking up rocks and sticking them in dirt.”

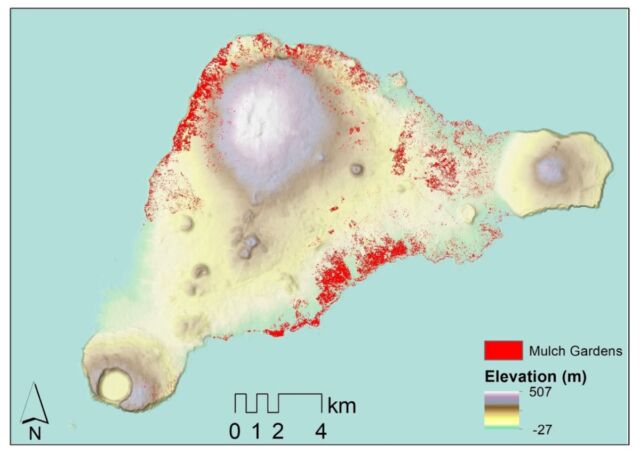

There had been only one 2013 study aimed at determining the island’s rock-garden capacity, which relied on near-infrared bands from satellite images. The authors of that study estimated that between 4.9 and 21.2 km2 of the island’s total area comprised rock gardens, although they acknowledged this was likely an inaccurate estimation.

Lipo et al. examined satellite imagery data collected over the last five years, not just in the near-infrared, but also short-wave infrared (SWIR) and other visible spectra. SWIR is particularly sensitive to detecting water and nitrogen levels, making it easier to pinpoint areas where lithic mulching occurred. They trained machine-learning models on archaeological field identifications of rock garden features to analyze the SWIR data for a new estimation of capacity.

The result: Lipo et al. determined that the prevalence of rock gardening was about one-fifth of even the most conservative previous estimates of population size on Easter Island. They estimate that the island could support about 3,000 people—roughly the same number of inhabitants European explorers encountered when they arrived. “Previous studies had estimated that the island was fairly covered with mulch gardening, which led to estimates of up to 16,000 people,” said Lipo. “We’re saying that the island could never have supported 16,000 people; it didn’t have the productivity to do so. This pre-European collapse narrative simply has no basis in the archaeological record.”

“We don’t see demographic change decline in populations prior to Europeans’ arrival,” Lipo said. “All the [cumulative] evidence to date shows a continuous growth until some plateau is reached. It certainly was never an easy place to live, but people were able to figure out a means of doing so and lived within the boundaries of the capacity of the island up until European arrival.” So rather than being a cautionary tale, “Easter Island is a great case of how populations adapt to limited resources on a finite place, and do so sustainably.”

DOI: Science Advances, 2024. 10.1126/sciadv.ado1459 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/?p=2031900