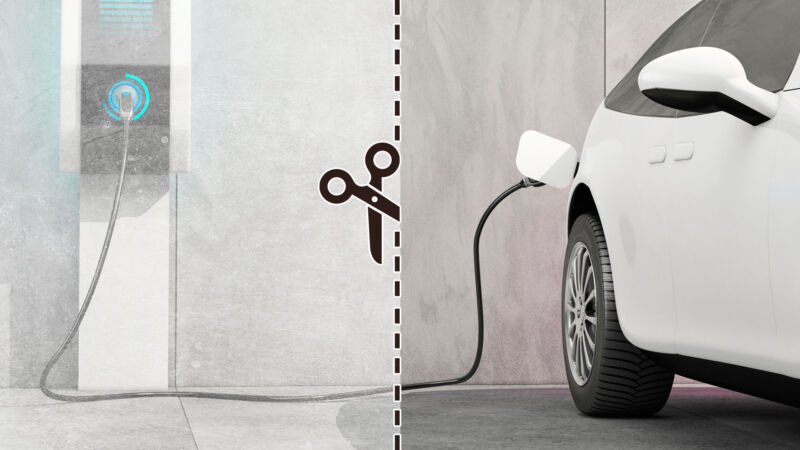

For much of the automobile’s existence, speed was the statistic that sold. But the move to electric vehicles is emphasizing range over performance—ironic given the EV’s inherent performance advantage here. While range remains a barrier to EV adoption, it takes second place to charging logistics. For about two-thirds of US drivers, the answer is simply to charge at home, parked in a garage or carport. But for the remaining third, that’s not possible, and that’s a problem.

From the post-war decades, a win at the racetrack or a new speed record translated to showroom success, both in the US and Europe. In turn, horsepower wars between automakers erupted every few years, steadily making our cars quicker and quicker. That trend is arguably accelerating—the near-instant torque of an electric motor means even SUVs that aren’t supposed to be that sporty are capable of 0-to-60 times that would rival a supercar not too long ago.

But when every EV can launch from a stoplight fast enough to give you whiplash, pretty soon everyone needs a new reason to one-up each other. The range fixation makes plenty of sense, given the long charging times and the difficulty that would ensue from completely running out of charge while out in the world. But in practice, most of us drive fewer than 30 miles a day, and many EVs fill their days running errands and commuting, returning home to recharge to 100 percent overnight.

That amounts to about 1.6 million homes, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation, and those numbers will increase as building codes are starting to require that new builds—both single- and multifamily—include some provision for EV charging. This is fine and dandy for people moving into new builds, but that still leaves people who street-park in the cold, as well as those of us who live in older multifamily developments with parking lots.

“The biggest headache is electrical upgrades, because many times you’ve got a client that’s waited a long time to make the decision, they’ve made the decision to invest in charging units, and then it’s a nine-month delay waiting for the utility to bring a new transformer and new panels or new switch plates or what have you,” said Mark LaNeve, president of Charge Enterprises, an infrastructure company.

“We’re dealing with a lot of owners, managers of multi-unit housing, condos, apartments, and it’s not only [the electrical delays], but it gets to ‘what’s the model going to be?’ If you have 100 residents, do you put in 10 level two chargers? And then who’s paying for it—do all residents pay for it, or just the residents who use it?” LaNeve asked.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1870902