In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica revelations regarding the exposure of profile data for millions of users, Facebook is now facing an investigation into its data-collection practices by the Federal Trade Commission. In a statement issued on March 26, FTC Consumer Protection Bureau Acting Director Tom Pahl said that the FTC “takes very seriously recent press reports raising substantial concerns about the privacy practices of Facebook. Today, the FTC is confirming that it has an open non-public investigation into these practices.”

The FTC investigation will likely focus on what data Facebook shares with third parties. But third parties aren’t the only entity hoping to win “friends” and influence people on this social platform. Facebook collects a great deal of information about users for use by its internal algorithms. Those algorithms govern who and what users see, whom they get recommended to “friend,” and other aspects of how our Facebook experiences are subtly (or sometimes not-so-subtly) shaped by advertisers and others leveraging the platform.

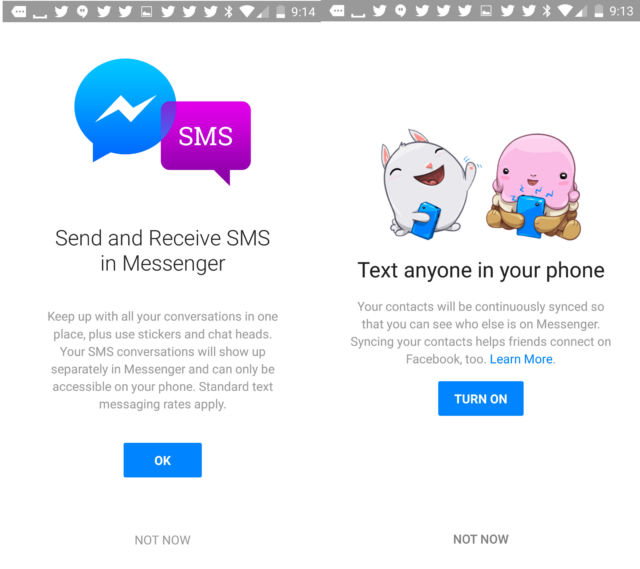

As Ars reported, Facebook has pushed users to allow access to SMS messages and call logs with its Messenger and Facebook Lite applications under the auspices of providing a service. “Keep up with all your conversations in one place” by using the app as the default SMS application on Android phones, Facebook offers. Previous versions of the Facebook mobile app on Android (in versions of Android prior to 4.1) were able to read SMS and call logs simply by asking for access to contacts, which Facebook has described as standard practice for applications. This allowed Facebook to keep track of the time, length, and contact information for any call made or received by the Android device by uploading it to Facebook’s data centers. Facebook could also access metadata about text and multimedia messages sent via SMS.

Facebook asserts that it does all of this tracking with users’ consent. The requests given for that consent, however, may be confusing and misleading, though they have become more explicit over the last two years.

Tinfoil hats not required

Some Facebook users have said that Facebook did more than just collect metadata from messages. Multiple individuals recounted to Ars occasions when they had the content of text message conversations nearly immediately affect advertisements they were shown on Facebook. These users say they saw ads that were specific to locations or services that were discussed via SMS, but those subjects were never the focus of Facebook posts or other Facebook content.

Other users reported that Facebook suggested friends after being in the same place as another person despite not having any friends or contacts in common—suggesting this is because of location data collected by Facebook. (Facebook had experimented with using location data for friend suggestions, but the company has claimed that it does not use specific location data.) And there are plenty of other cases of eerie coincidences in Facebook content, like some people even insisting that Facebook is surreptitiously recording their conversations.

Facebook probably doesn’t need to go that far. Much of that coincidence is derived from the power of Facebook’s “social graph” database and the technology Facebook developed to power its search features. Graph databases link “entities” (people, products, interests, locations) with relationships, making it possible for algorithms to crawl down the connections between different entities to uncover hidden potential affinities or relationships. And features like plugging into call and SMS data, SMS text flow, data from sites carrying Facebook-hosted advertisements or “like” and “share” buttons, and location data from mobile allow Facebook to make those sorts of connections dynamically, in near-real time.

Those sorts of connections aren’t obvious to users who download archives of their Facebook data, but they are certainly suggested by parts of it. The “Ads Topics” data that was in my personal Facebook archive included very specific terms linked to my pattern of life: specific people I have interacted with, services I have looked at websites related to (“Kitchen” is a recent high-scoring one, thanks to searches related to remodeling plans), places I have visited or may be interested in, and organizations I either have an affiliation with or a research interest in.

These could be valuable to all sorts of organizations, including nation-states; my Ads Topics of “Noam Chomsky,” “North Korea,” “US Department of Defense,” and the New York City and Baltimore Police Departments could be interpreted in all sorts of ways when taken together, for example.

Government and law enforcement agencies tap directly into Facebook’s rich store of data for just such purposes, and Facebook is legally obliged to let them. The Intercept reports that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) used Facebook data to track down immigrants by obtaining phone data and other information. Last fall, Facebook won the right to reveal when it had disclosed users’ data under a warrant when the Justice Department ended the practice of Non-Disclosure Orders for such warrants.

Google collects similar data on users. You can relive your travels courtesy of Google Timeline with sometimes disconcerting fidelity: all the places you’ve gone with your Android phone, the routes you took, the photos you took along the way in a handy Google Maps format. Google’s algorithms and cookies follow your searches and page visits to sites with Google and Doubleclick advertisements, and the bots read the contents of your emails to deliver the targeted advertisements that pay for those services.

All of this data is collected, as with Facebook’s collection, with your implied permission. And as with Facebook, the raw data is not directly readable by third parties (other than law enforcement agencies).

But the data Google collects contains significantly less direct and inferred information about an individual’s relationships, affiliations, activities, and intents. While Google has an entity database technology of its own among other “big data” systems used as part of its search and advertising services, it has not yet applied that power in a way that mirrors Facebook’s global social graph.

So, it’s important to remember one underlying truth when using any of these “free” services owned by Google, Facebook, Snap, Twitter, and the like: we users are not their customers; we’re their product.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1282673