The state of Alabama has filed an Admiralty claim for ownership of the wreckage of the last ship to smuggle enslaved people from Africa to the United States. Archaeologists identified the wreck in an arm of the Mobile River earlier this summer. The new claim could help provide some legal protection for the wreck, but the details of its future remain to be decided.

Burned and sunk in 20 feet of water

In 1860, the US had long since outlawed the import of slaves (but not the practice of slavery itself or the sale of enslaved people born on US soil). Wealthy Mobile landowner Timothy Meaher hired ship captain William Foster to smuggle 110 captives from West Africa into Alabama—mostly to make a profit, of course, but reportedly also partly just to prove that he could. In total, 109 men, women, and children survived the crossing in the hold of the schooner Clotilda.

After offloading his human cargo onto Meaher’s brother’s riverboat, Foster sailed up a bayou, where (according to his own handwritten account) he burned and sunk the Clotilda in 20 feet of water. It was the only way to destroy the evidence of his crime: the unmistakable stench of human waste that permeated the very wood of the ship. The 109 people who survived endured four years of slavery before the end of the Civil War, and they never returned home. Today, many of their descendants still live near Mobile.

“I think they all grew up hearing the stories, but as we’ve seen with other archaeological discoveries, the reality of locating the physical remains very much brings it forward into the present,” nautical archaeologist James Delgado of Search, Inc. told Ars.

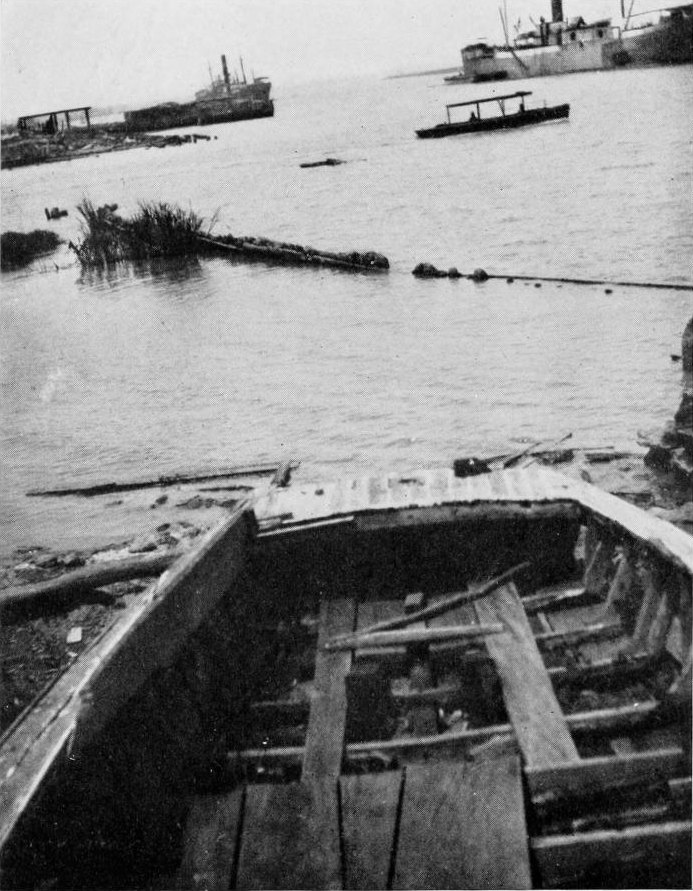

Finding the ship was a daunting task. It started when local investigative reporter Ben Raines spotted a wreck sticking out of the water at low tide in January 2018, a find that made its way to National Geographic. At that point, the search was on in earnest. A team of archaeologists from the National Geographic Society, the Alabama Historical Commission, private firm Search, Inc., and other institutions surveyed an arm of the Mobile River that had never been dredged and had a long history as a dumping ground for defunct ships.

The river is muddy and littered with fallen trees and at least 14 other shipwrecks, but with side-scan sonar, magnetometers, a sub-bottom profiler, and hours of diving in the dark, rushing water, eventually the team narrowed its focus to one wreck in particular. Most of the hull below the ship’s waterline survived intact, along with parts of the upper hull. The whole wreck lay half-buried in river sediment, which revealed only the bow and the middle of the ship, but that was enough to let the archaeologists reconstruct its dimensions.

Archaeology by Braille

Delgado and his colleagues spent hundreds of hours combing through historical archives, looking at registries for over 1,500 schooners working in the Gulf in the mid-1800s. Based on the archaeologists’ careful measurements of the wreck, it would have been a good match for Clotilda‘s 120-ton hold and 86-foot length. And the wood type was right. “The insurance documents said Clotilda had white oak frames and southern yellow pine planks, and that’s exactly what the analysis showed in multiple samples,” Delgado told Ars.

Those details made the wreck a likely match, but they weren’t conclusive proof. Other evidence, however, also pointed to Clotilda. Archaeologists found heat-warped metal fasteners with charred bits of white oak frame still clinging to them, clearly suggesting that the ship had burned. And it lay in 20 feet of water, exactly where Foster’s account said it should be.

Sometime in its history, someone had blasted the starboard side of the wreck apart with dynamite, bending sturdy timbers outward like porcupine spines and blowing a heavy cast-iron piece of the ship’s bilge pump 20 feet away. That damage also lined up well with historical documents the team dug up in local archives, which recorded that the Meaher family had dynamited the wreck to remove its copper hull sheathing, apparently in an attempt to recoup more of their investment in outfitting the ship for its journey.

“Ultimately, what we had is a very strong line of circumstantial evidence that ultimately passed beyond the point of reasonable doubt,” Delgado said.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1544967