A new study describes the complex ecosystems of bacteria and fungi that live and feast on a 17th-century painting—and how other species of bacteria may one day help art conservators fight back.

If you could zoom in for a microscopic look at an oil painting on canvas, you would see many thin, overlapping layers of pigments—powdered bits of insects, plants, or minerals—held together with oils or glue made from animal collagens. Many of those pigments and binding materials are surprisingly edible to bacteria and fungi. Each patch of color and each layer of paint and varnish in an oil painting offers a different microbial habitat. So when you look at a painting, you’re not just looking at a work of art; you’re looking at a whole ecosystem.

Microbes’ artistic taste

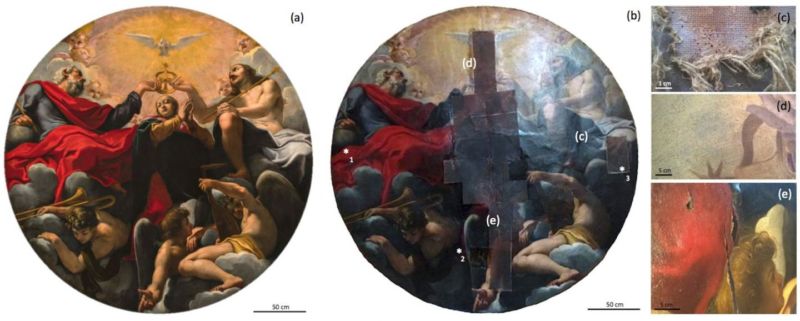

To better understand these microscopic art vandals, University of Ferrara microbiologist Elisabetta Caselli and her colleagues turned to a Renaissance painting called “Incoronazione della Virgine,” by painter Carlo Bononi. The painting once adorned the ceiling of the Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado, Italy. When an earthquake damaged the church in 2012, staff took down the 2.8 meter (9.18 foot) round canvas from where it had hung since 1620 and leaned it against the wall in an inner niche of the church.

The team took a small 4mm (0.16 inch) square sample from alongside an area of the painting that had already been damaged over the centuries. Using X-ray fluorescence, they studied the chemical makeup of the layers of pigment and varnish Bononi used to create the image.

The results reveal the complex chemistry of an oil painting: copper oxides in the blues and greens, lead and tin in the whites and bright yellows (one of the many reasons you shouldn’t lick Renaissance artwork), cinnabar in some bright reds, and iron oxides in the reds, browns, and yellows. And the red paint in the upper layers of the painting bears the chemical signature of red lac (or red lake), a dye made from the laccaic acid found in parts of plants or insects. Under the right conditions, some of those materials can provide the perfect nutrients for microbial communities to thrive.

Previous studies found that some species of bacteria and fungi did, in fact, chow down on pigments made from laccaic acid and ochres. Over time, the painting’s bright colors appeared to fade because the microbes were literally eating them away.

Still life with microbes

There was no sign of microbial damage to “Incoronazione,” but Caselli and her colleagues found a thriving ecosystem on the 400-year-old canvas. In layers of dark brown and red paint, they found mold species of Aspergillus and Penicillium, which are common nuisances in libraries and museums thanks to their fondness for paper and paintings. In some yellow and pink areas, microscopic examination revealed spores of fungi from the genus Cladosporium. Several species of bacteria from the genus Staphylococcus also turned up, which helped settle a longstanding debate among art conservators.

“Our results confirmed that [Staphylococci] could be found at a high frequency on oil paintings, providing evidence that Staphylococci are painting-colonizing and were not just human skin contaminants transported accidentally to the canvas,” Caselli and her colleagues wrote. And on the back side of the canvas, several species of Bacillus bacteria had set up housekeeping, apparently feeding on paste and glue.

The results showed that different species of fungi and bacteria feed on different pigments and thrive in different environmental conditions. Caselli and her colleagues say it’s likely that fungi and bacteria might lie dormant, hidden away between paint layers, for centuries, but if the temperature and humidity are just right, a priceless painting can be a fertile breeding ground for the destructive microbes. Understanding which species might grow and feed on different areas of a painting can help museums preserve artwork against the ravages of time and microbiology.

And one tool in the fight against destructive microbes might be… other microbes. In the lab, Caselli and her colleagues attacked cultures of bacteria and fungi from the “Incoronazione” samples with spores from three Bacillus species. The Bacillus spore mixture has already been tested against destructive microbes eating away at stonework on a 20th-century building, and Caselli and her colleagues say the results gave them reason to think biological warfare might be the answer for preserving oil paintings, too.

The Bacillus spores out-competed the art-munching microbes well enough to almost completely stop them from growing. But that doesn’t mean it’s time for art museums to douse their masterpieces with spores. Caselli and her colleagues say they need to follow up with several more studies to make sure the Bacillus spores won’t eventually damage the paintings they’re trying to save.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1426223