Men often judge women by their appearance. Turns out, computers do too.

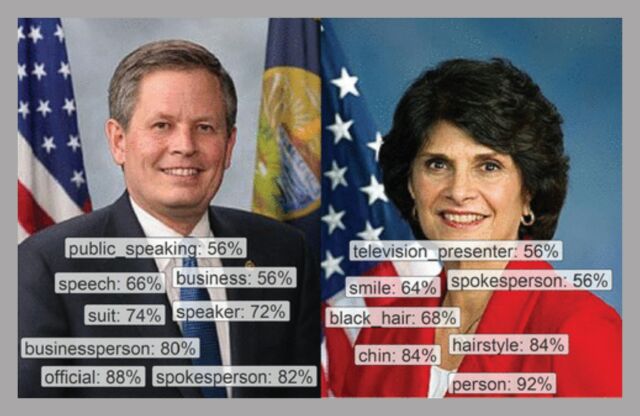

When US and European researchers fed pictures of members of Congress to Google’s cloud image recognition service, the service applied three times as many annotations related to physical appearance to photos of women as it did to men. The top labels applied to men were “official” and “businessperson”; for women they were “smile” and “chin.”

“It results in women receiving a lower-status stereotype: that women are there to look pretty and men are business leaders,” says Carsten Schwemmer, a postdoctoral researcher at GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences in Köln, Germany. He worked on the study, published last week, with researchers from New York University, American University, University College Dublin, University of Michigan, and nonprofit California YIMBY.

The researchers administered their machine vision test to Google’s artificial intelligence image service and those of rivals Amazon and Microsoft. Crowdworkers were paid to review the annotations those services applied to official photos of lawmakers and images those lawmakers tweeted.

The AI services generally saw things human reviewers could also see in the photos. But they tended to notice different things about women and men, with women much more likely to be characterized by their appearance. Women lawmakers were often tagged with “girl” and “beauty.” The services had a tendency not to see women at all, failing to detect them more often than they failed to see men.

The study adds to evidence that algorithms do not see the world with mathematical detachment but instead tend to replicate or even amplify historical cultural biases. It was inspired in part by a 2018 project called Gender Shades that showed that Microsoft’s and IBM’s AI cloud services were very accurate at identifying the gender of white men but very inaccurate at identifying the gender of Black women.

The new study was published last week, but the researchers had gathered data from the AI services in 2018. Experiments by WIRED using the official photos of 10 men and 10 women from the California State Senate suggest the study’s findings still hold.

All 20 lawmakers are smiling in their official photos. Google’s top suggested labels noted a smile for only one of the men, but for seven of the women. The company’s AI vision service labeled all 10 of the men as “businessperson,” often also with “official” or “white collar worker.” Only five of the women senators received one or more of those terms. Women also received appearance-related tags, such as “skin,” “hairstyle,” and “neck,” that were not applied to men.

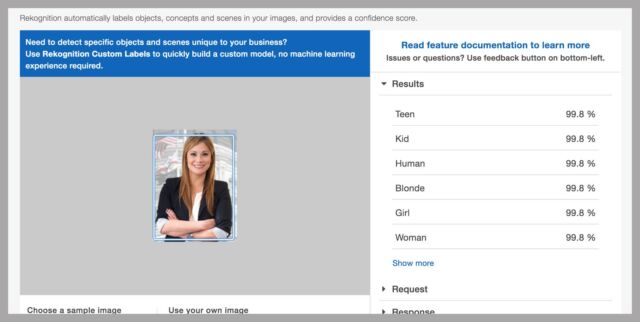

Amazon and Microsoft’s services appeared to show less obvious bias, although Amazon reported being more than 99 percent sure that two of the 10 women senators were either a “girl” or “kid.” It didn’t suggest any of the 10 men were minors. Microsoft’s service identified the gender of all the men but only eight of the women, calling one a man and not tagging a gender for another.

Google switched off its AI vision service’s gender detection earlier this year, saying that gender cannot be inferred from a person’s appearance. Tracy Frey, managing director of responsible AI at Google’s cloud division, says the company continues to work on reducing bias and welcomes outside input. “We always strive to be better and continue to collaborate with outside stakeholders—like academic researchers—to further our work in this space,” she says. Amazon and Microsoft declined to comment; both companies’ services recognize gender only as binary.

“False image of reality”

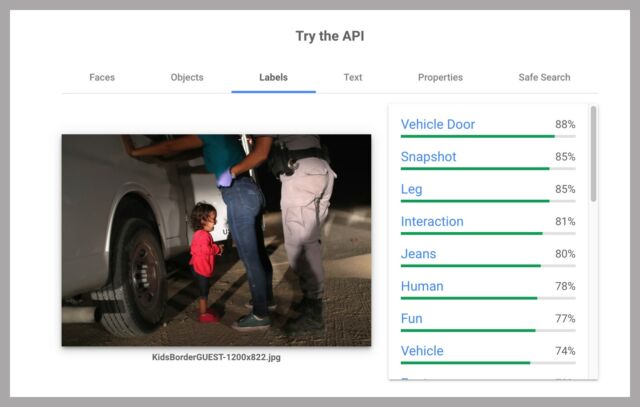

The US-European study was inspired in part by what happened when the researchers fed Google’s vision service a striking, award-winning image from Texas showing a Honduran toddler in tears as a US Border Patrol officer detained her mother. Google’s AI suggested labels including “fun,” with a score of 77 percent, higher than the 52 percent score it assigned the label “child.” WIRED got the same suggestion after uploading the image to Google’s service Wednesday.

Schwemmer and his colleagues began playing with Google’s service in hopes it could help them measure patterns in how people use images to talk about politics online. What he subsequently helped uncover about gender bias in the image services has convinced him the technology isn’t ready to be used by researchers that way and that companies using such services could suffer unsavory consequences. “You could get a completely false image of reality,” he says. A company that used a skewed AI service to organize a large photo collection might inadvertently end up obscuring women businesspeople, indexing them instead by their smiles.

Prior research has found that prominent datasets of labeled photos used to train vision algorithms showed significant gender biases, for example showing women cooking and men shooting. The skew appeared to come in part from researchers collecting their images online, where the available photos reflect societal biases, for example by providing many more examples of businessmen than businesswomen. Machine-learning software trained on those datasets was found to amplify the bias in the underlying photo collections.

Schwemmer believes biased training data may explain the bias the new study found in the tech giant’s AI services, but it’s impossible to know without full access to their systems.

Diagnosing and fixing shortcomings and biases in AI systems has become a hot research topic in recent years. The way humans can instantly absorb subtle context in an image while AI software is narrowly focused on patterns of pixels creates much potential for misunderstanding. The problem has become more pressing as algorithms get better at processing images. “Now they’re being deployed all over the place,” says Olga Russakovsky, an assistant professor at Princeton. “So we’d better make sure they’re doing the right things in the world and there are no unintended downstream consequences.”

-

An academic study and tests by WIRED found that Google’s image recognition service often tags women lawmakers like California state Sen. Cathleen Galgiani with labels related to their appearance…Wired staff via Google

-

… but sees men lawmakers like her colleague Jim Beall as businesspeople and elders.Wired staff via Google

One approach to the problem is to work on improving the training data that can be the root cause of biased machine-learning systems. Russakovsky is part of a Princeton project working on a tool called REVISE that can automatically flag some biases baked into a collection of images, including along geographic and gender lines.

When the researchers applied the tool to the Open Images collection of 9 million photos maintained by Google, they found that men were more often tagged in outdoor scenes and sports fields than women. And men tagged with “sports uniform” were mostly outdoors playing sports like baseball, while women were indoors playing basketball or in a swimsuit. The Princeton team suggested adding more images showing women outdoors, including playing sports.

Google and its competitors in AI are themselves major contributors to research on fairness and bias in AI. That includes working on the idea of creating standardized ways to communicate the limitations and contents of AI software and datasets to developers—something like an AI nutrition label.

Google has developed a format called “model cards” and published cards for the face and object-detection components of its cloud vision service. One claims Google’s face detector works more or less the same for different genders but doesn’t mention other possible forms that AI gender bias might take.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1724806