On Friday, the World Health Organization officially named a new version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus a variant of concern, and attached the Greek letter omicron to the designation. The Omicron variant is notable for the sheer number of mutations in the spike protein of the virus. While Omicron appears to have started spreading in Africa, it has already appeared in European countries like Belgium and the UK, which are working to limit its spread through surveillance and contact tracing.

As of now, the data on the variant is very limited; we don’t currently know how readily it spreads compared to other variants, nor do we understand the degree of protection against Omicron offered by vaccines or past infections. The new designation, however, will likely help focus resources on studying Omicron’s behavior and tracing its spread.

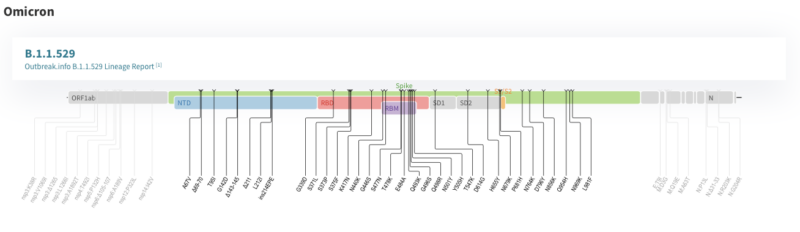

Many changes

While the Delta variant’s version of spike has nine changes compared to the virus that started the pandemic, Omicron has 30 differences. While many of these haven’t been identified previously, a number of these have been seen in other strains, where they have a variety of effects. These include increasing infectiveness of the virus, as a number of the changes increase the affinity between the spike protein and the protein on human cells that it targets when starting a new infection.

Others changes in the spike occur in areas of the protein that are frequently targeted by antibodies that neutralize the virus. Changes here can mean that an immune response generated to vaccines or earlier versions of the virus are less able to target Omicron.

While these mutations are suggestive, understanding how they and the previously undescribed mutations in Omicron alter its behavior will depend on getting real-world data on its spread. Right now, however, we just don’t have much of that.

We are lucky in the sense that it’s relatively easy to detect Omicron. According to the WHO, some of the large collection of mutations in the gene that encodes the spike protein interfere with the gene’s recognition by common versions of PCR tests. Those tests continue to recognize the presence of the virus by also targeting other areas of the genome. So a PCR test that comes back spike-negative but virus-positive is suggestive of the presence of Omicron, which can then be confirmed by genome sequencing.

These tests have shown Omicron is spreading rapidly within a number of countries in southern Africa, although the total cases in Botswana and South Africa remain relatively low at the moment, so the significance of this spread is unclear. Vaccination rates in these countries also remain low, making it difficult to determine how much of a risk Omicron poses to those who have been immunized.

Some constants

The cases identified outside of southern Africa so far have all been in travelers who spent time in this region. Public health authorities in those countries are currently engaged in contact tracing to try to limit the variant’s spread outside of those already infected. and a number of countries (including the US) have already limited travel from countries in the region.

Testing and contact tracing are part of the now-familiar suite of public health measures that can limit the impact of Omicron while we’re learning more about it. A statement from the CDC provides a reminder of the rest: social distance, mask when indoors, and get a vaccine if you are eligible. While we remain uncertain how much protection vaccines provide against Omicron, it’s quite certain that their effectiveness against it is considerably greater than zero.

Listing image by Aurich Lawson / Getty

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1816265