Windows 11 promises to refine window management, run Android apps, and to unify the look and feel of the operating system’s built-in apps after years of frustrating hodgepodge. But none of that matters if your computer can’t run the software, and Microsoft has only promised official Windows 11 support for computers released within the last three or four years. Anyone else will be able to run the operating system if they meet the performance requirements, but they’ll need to jump through the hoop of downloading an ISO file and installing the operating system manually rather than grabbing it through Windows Update.

This is a break from previous versions of Windows, which up until now have had more or less the same system requirements for a decade. Microsoft actually used the ability to run on older hardware as a selling point for Windows 10, making it available as a free upgrade to all computers running Windows 7 and Windows 8—if you get as many people as possible using the newest version of Windows, the reasoning went, it would be easier to get developers to take advantage of the latest features.

Microsoft’s rationale for Windows 11’s strict official support requirements—including Secure Boot, a TPM 2.0 module, and virtualization support—has always been centered on security rather than raw performance. A new post from Microsoft today breaks down those requirements in more detail and also makes an argument about system stability using crash data from older PCs in the Windows Insider program.

Drivers and stability

Microsoft says that Insider Program PCs that didn’t meet Windows 11’s minimum requirements “had 52% more kernel mode crashes” than PCs that did and that “devices that do meet the system requirements had a 99.8% crash-free experience.” According to Microsoft, this mostly comes down to active driver support. Newer computers mostly use newer DCH drivers, a way of packaging drivers that Microsoft began supporting in Windows 10. To be DCH-compliant, a driver must install using only a typical .INF file, must separate out OEM-specific driver customizations from the driver itself, and must distribute any apps that accompany your driver (like a control panel for an audio driver or GPU) through the Microsoft Store. DCH drivers are common for hardware made in the last four or five years but rare to nonexistent for hardware that shipped in the Windows 8 or Windows 7 eras.

Certainly, computers from 2012 or 2014 are going to be running outdated drivers that cause crashes—using Windows 7-era drivers on older computers running Windows 10 can lead to instability or general weirdness. But Microsoft’s numbers make no distinction between these older systems and newer computers that nearly, but don’t quite, miss the system requirements, like 6th- and 7th-generation Intel Core systems and first-generation Ryzen systems that include TPM 2.0 modules and still enjoy active DCH driver support from Intel, AMD, and (in many cases) the companies that manufactured the computers. Presumably, installing Windows 11 manually on these PCs will feel more or less as stable as installing it on an officially supported device, but it’s something we’ll need to test for ourselves.

A towering stack of security acronyms

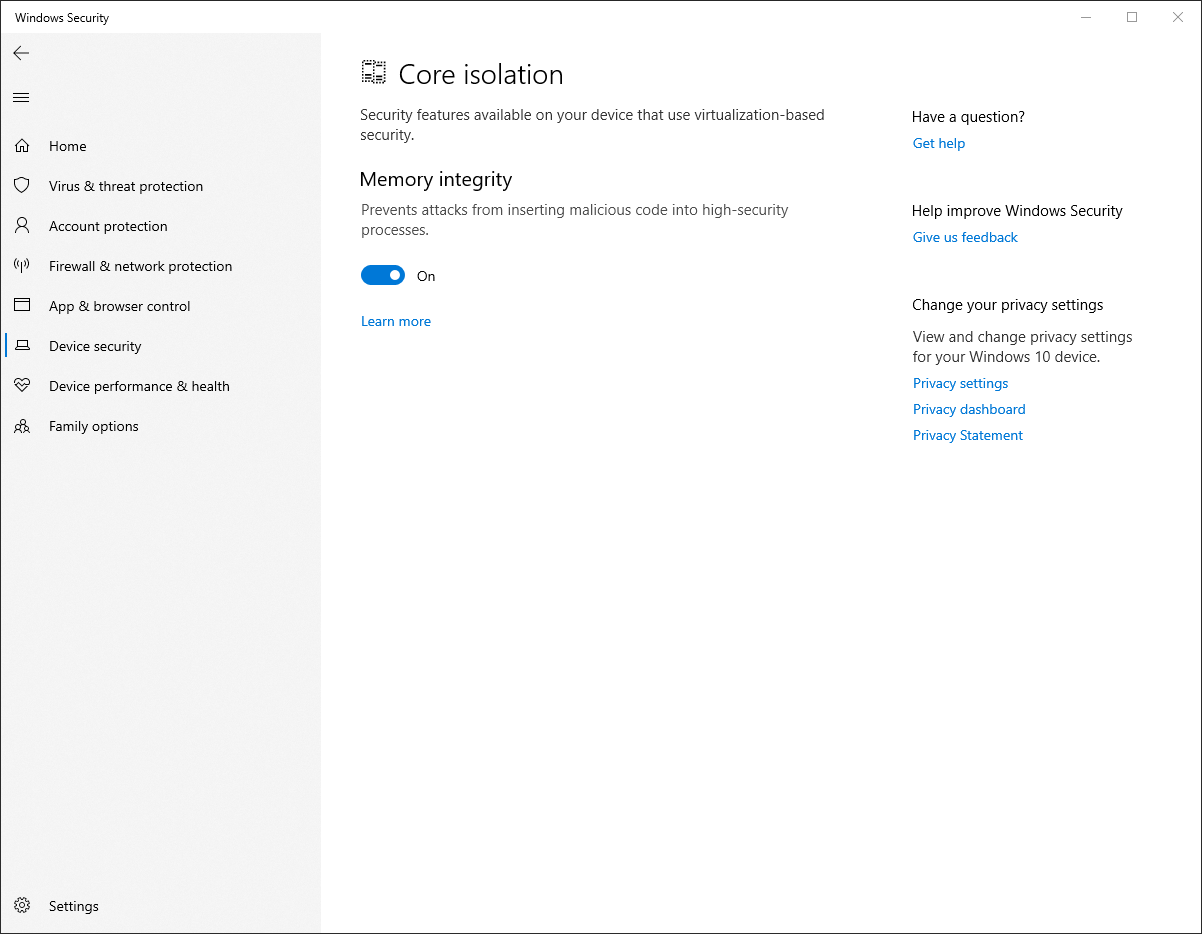

That’s where the security requirements come back into play. Microsoft goes to greater lengths to explain the benefits of using Secure Boot and TPM 2.0 modules, but the key may actually be the less-discussed virtualization requirement and an alphabet soup of acronyms. Windows 11 (and also Windows 10!) uses virtualization-based security, or VBS, to isolate parts of system memory from the rest of the system. VBS includes an optional feature called “memory integrity.” That’s the more user-friendly name for something called Hypervisor-protected code integrity, or HVCI. HVCI can be enabled on any Windows 10 PC that doesn’t have driver incompatibility issues, but older computers will incur a significant performance penalty because their processors don’t support mode-based execution control, or MBEC.

And that acronym seems to be at the root of Windows 11’s CPU support list. If it supports MBEC, generally, it’s in. If it doesn’t, it’s out. MBEC support is only included in relatively new processors, starting with the Kaby Lake and Skylake-X architectures on Intel’s side, and the Zen 2 architecture on AMD’s side—this matches pretty closely, albeit not exactly, with the Windows 11 processor support lists.

It’s easiest to think of MBEC as hardware acceleration for the memory integrity feature, sort of like how AES-NI instructions sped up encryption operations a decade or so ago. Computers without AES-NI can still use BitLocker drive encryption, for example, it just comes with a more noticeable performance penalty. The same thing is true of the memory integrity feature and MBEC—PCs without processors that support MBEC rely on software emulation called “Restricted User Mode,” which does get you the security benefits but affects performance more. Some users who have tested the HVCI feature in Windows 10 on processors without MBEC support have noticed performance reductions of up to 40 percent, though this will depend on the tasks you’re doing and the computer you’re using.

The memory integrity feature is fully present in Windows 10—the “secured-core PC” initiative launched in late 2019 mandates support for all of the Windows 11 security requirements plus a few others. But for most PCs, HVCI is usually disabled by default on all but the newest systems. Microsoft instructs OEMs to enable HVCI by default on all 11th-generation Intel Core PCs, anything with one of AMD’s Zen 2 or Zen 3 processors (which covers Ryzen 3000, 4000, and 5000-series chips), and the Qualcomm Snapdragon 8180 SoC and newer; they also require at least 8GB of RAM and a 64GB or larger SSD. If you’re building a PC and perform a fresh install of Windows 10 yourself, HVCI won’t be enabled by default even if you meet those requirements.

So if Microsoft is mandating MBEC-accelerated HVCI support (what a sentence) on all Windows 11 PCs, then surely it’s changing the default security settings to take advantage of those features? According to the company’s blog post, the answer is currently no, at least not on existing PCs (emphasis ours):

“While we are not requiring VBS when upgrading to Windows 11, we believe the security benefits it offers are so important that we wanted the minimum system requirements to ensure that every PC running Windows 11 can meet the same security the [US Department of Defense] relies on. In partnership with our OEM and silicon partners, we will be enabling VBS and HVCI on most new PCs over this next year. And we will continue to seek opportunities to expand VBS across more systems over time.”

Assuming that full HVCI and MBEC hardware support are what is driving the new Windows 11 requirements, there are still odd inclusions and exclusions from the supported processor lists. Why are only a handful of high-end 7th-generation Intel Core chips officially supported, even though Microsoft’s own Windows 10 documentation says that HVCI works on all Kaby Lake processors? And why are AMD Zen+ processors like the Ryzen 2000-series CPUs and 3000-series APUs included on the support list, even though AMD only apparently added MBEC support starting with the Zen 2 architecture? These are questions we hope to get answers to by the time Windows 11 is released to the public this fall.

https://arstechnica.com/?p=1790182